The untold story of how booze soaked the battlefields of World War II

America's battle against alcohol in the 1920s failed to attract many foreign allies and ended in defeat. By the time World War II broke out, the nation's short-lived prohibition experiment had long ended

America's battle against alcohol in the 1920s failed to attract many foreign allies and ended in defeat. By the time World War II broke out, the nation's short-lived prohibition experiment had long ended. In some countries, such as France, drinking had been celebrated and encouraged during the interwar years, and consumption surged. Indeed, the French remained so devoted to their wine that securing enough wine for the troops was deemed essential to mobilizing for the next war. A third of the country's railroad cars designed to carry liquid in bulk were reserved for transporting wine to the front lines. When Germany attacked France in May 1940, 3,500 trucks were tasked with delivering two million liters per day to the troops.

But when France fell to the Germans within two months, praise turned to condemnation. Wine was blamed for making the country soft. Philippe Petain, the WWI hero who had credited wine for saving France, now pointed a finger at drunkenness for “undermining the will of the army.” He became the leader of the collaborative government of Vichy, where new restrictions on the sale of alcohol were quickly imposed, including setting a minimum drinking age for the first time (no one under 14 could purchase alcohol).

The British fought on with their daily rum rations. “We simply kept going on rum,” recalled one soldier. “Eventually it became unthinkable to go into action without it.” But German u-boats targeting shipping lanes made it much harder for the British to secure rum supplies from the West Indies. “Things became so critical in 1943,” writes Captain James Pack, “that the Admiralty was forced to seriously consider discontinuing rum which, for reasons of morale, the board was loathe to do.”

The British government had a noticeably more relaxed attitude toward alcohol than during WWI. This was symbolized by Winston Churchill's candid views on the matter: “My rule of life prescribe as an absolutely sacred rite smoking cigars and also the drinking of alcohol before, after, and if need be during all meals and in the intervals between them.” Churchill typically started his day with a glass of champagne or a weak whisky and water, drank more whisky and water between meals, and enjoyed wine with lunch and dinner.

In 1940, Lord Woolton, the British minister for food, declared beer drinking to be essential for public morale: “If we are to keep up anything like approaching the normal life of the country, beer should continue to be in supply, even though it may be beer of a rather weaker variety than the connoisseurs would like. It is the business of the Government not only to maintain the life but the morale of the country.” Unstated was that beer was also helping to pay for the war: the beer tax was increased three times between September 1939 and July 1940. The tax on increasingly scarce whiskey supplies was also nearly doubled.

Whereas pubs and alcohol were treated as threats during WWI, now they were promoted as essential to the war effort. As one beer advertiser observed, “At no other time in British history had an intoxicating drug enjoyed so much symbolic importance.” Keeping the beer flowing, however, became increasingly challenging as the war dragged on. Many London breweries suffered direct hits from German bombers. Finding a place to drink also became harder: by 1943, thirteen hundred pubs had been destroyed by German attacks.

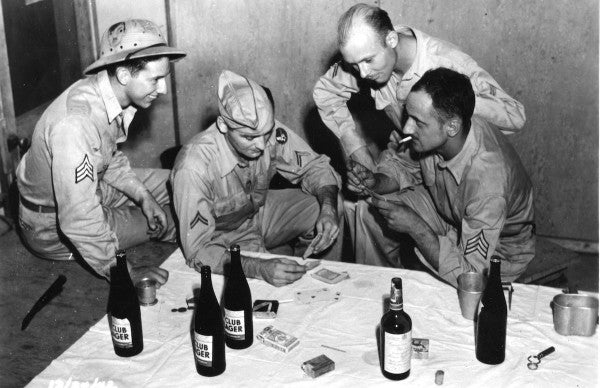

With prohibition long abandoned, American soldiers sent off to fight were no longer expected to stay dry. Beer in particular was considered so important to troop morale that the government instructed the brewing industry to allocate 15 percent of their production for the military effort. Brewers were more than happy to oblige, launching an aggressive public relations campaign touting their many contributions to the war, including tax payments to support war production. Having made a full recovery from their abject vilification in WWI, American brewers were now considered promoters of patriotism. The government also supplied defense workers with beer in the belief that it would help their productivity. To keep the beer flowing, the government gave brewers privileged access to rationed goods (such as rubber, gasoline, and tin cans), and granted them status as an essential wartime industry.

Meanwhile, the Nazis denounced drunkards but did plenty of drinking. Hitler himself rarely drank, and soldiers who committed crimes under the influence faced the death penalty. The victims of a sterilization program included several thousand alcoholics, and thousands more were shipped off to concentration camps as “undesirables” and “deviants.” The government announced that, “No dangerous alcoholic, no person who has fallen under the influence of alcohol may…remain unknown to the state and party.” In 1939, the Bureau against the Dangers of Alcohol and Tobacco was created, initiating a wave of restrictions on alcohol. Alcohol taxes were increased and new limits on production and sale were introduced.

The new rules also included restrictions on alcohol use in the military, but Hitler's commanders on the ground often had a more tolerant attitude. One German soldier on the Eastern Front wrote, “Those who were neither asleep, on guard, playing cards, nor writing letters were absorbing the alcohol which was freely distributed along with our ammunition.” A wounded German soldier observed: “There's as much vodka, schnapps and Terek liquor on the front as there are Paks .”

Alcohol, which facilitated desensitization, was also supplied to German soldiers and police tasked with carrying out some of the most horrendous atrocities of the war. This included extra alcohol rations to the men in the Reserve Police Battalions in Poland who shot tens of thousands of Jewish men, women, and children at close range. Historian Edward Westernmann documents how alcohol not only lowered inhibitions but also fostered social bonding and helped to incentivize and reward genocidal killing. In the occupied Eastern territories, members of the ruthless Schutzstaffel (SS) regularly participated in celebratory post-execution drinking rituals.

Alcohol was equally important within concentration camps, with alcohol flowing freely amongst SS-personnel at both Auschwitz and Treblinka during mass killings. One Treblinka survivor recalled observing “SS-men who held a pistol or truncheon in one hand, whiskey bottle in the other.” The doctors charged with running the gas chambers were also well-lubricated with alcohol. By their own admission, drinking was part of the job: “The selections were mostly an ordeal. Namely to stand all night. And it wasn't just standing all night—but the next day was completely ruined because one got drunk every time….A certain number of bottles were provided for each section and everybody drank and toasted the others….One could not stay out of it.”

To the west, meanwhile, the German occupation of France included the country's most prized wine producing areas—Burgundy, Bordeaux, and Champagne. The Nazis extracted an average of almost 900,000 bottles a day during the occupation period. The extraction of French wine was overseen by Herman Goering, who expressed no remorse: “In the old days, the rule was plunder. Now, outward forms have become more humane. Nevertheless, I intend to plunder, and plunder copiously.” In addition to securing wine shipments for his fellow military officers, he stocked his private cellar with more than ten thousand bottles of the country's best wines.

In Champagne, producers frantically hid their prized supplies. But their efforts failed to keep the Germans from quenching their thirst for France's most famous drink. An estimated two million bottles of champagne were stolen in the first chaotic months of occupation. Some producers resisted by relabeling bad wine as good, watering down the good wine, using bad corks, and even substituting water for wine in barrels being shipped to Germany. Technically, the occupiers paid for what they consumed, but since they set the value of the mark at five times its pre-war value, this essentially amounted to what one producer bitterly described as “legalized plunder.”

Meanwhile, in the wake of the failed Bolshevik temperance campaign in Russia, alcohol returned in full force to the Red Army, with the vodka ration in 1942 set at a hundred grams per man per day. And toward the end of the war, as Soviet forces advanced into Germany they supplemented their ration with looted alcohol. As they retreated, the Germans purposefully left their alcohol stocks behind, calculating that a drunk Soviet soldier would be less effective. But the reality was that the Soviets had such an abundance of manpower that no amount of alcohol was going to stop them, and in the end it was the German civilian population, especially women, that suffered the most at the hands of intoxicated Soviet soldiers. Heavy drinking within the Soviet military went all the way to the top: Stalin told British foreign minister Anthony Eden that his generals “fought better when they were drunk.”

Peter Andreas is the John Hay Professor of International Studies at Brown University, where he holds a joint appointment between the Department of Political Science and the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs.

From Killer High: A History of War in Six Drugs by Peter Andreas. Copyright © 2020 by Peter Andreas and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved