The Air Force Is Terrible At Reporting Its Criminals. The Other Branches Are Even Worse

Nearly a month after disgraced former airman Devin Patrick Kelley massacred 26 worshipers in a Texas church with guns he...

Nearly a month after disgraced former airman Devin Patrick Kelley massacred 26 worshipers in a Texas church with guns he was able to buy legally but shouldn’t have been, the Department of Defense has published a bleak audit of the U.S. armed forces’ compliance with criminal reporting procedures: Nearly a third of those service members convicted of military crimes that should have barred them from buying firearms — including rape, murder, conspiracy, and domestic violence — went unreported to federal law enforcement.

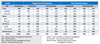

That report, published Dec. 4 by the Pentagon inspector general, found that the Military Services Law Enforcement Organizations (LEOs) failed to consistently submit 31% of their final disposition reports and 24% of the required fingerprint cards to the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Next Generation Identification (NGI), federal law enforcement’s primary fingerprint repository, in 2015 and 2016. Failing to report an offender’s fingerprints to the NGI “can allow someone to purchase a weapon who should not,” according to the DoD IG report — just as Kelley managed to purchase the firearms used in his Nov. 4 mass shooting after the Air Force failed to report his 2012 court-martial conviction for domestic violence to the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS), which relies on NGI data.

Each missing submission violates DoD Instruction 5505.11, which requires all branches to submit their offender criminal history data to the FBI for inclusion in the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database. But the administrative failures detailed in the inspector general’s report take on greater significance in the aftermath of the Texas church killings.

Law enforcement officials investigate a mass shooting at the First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, Texas, on Sunday, Nov. 5, 2017.Photo via Nick Wagner/Austin American-Statesman/Associated Press

Based on the audit's results, it appears the Air Force is already improving its criminal reporting procedures. While the branch admitted on Nov. 28 that it had identified some 60,000 serious incidents involving airmen that went unsubmitted to federal databases since 2002, the DoD IG report indicates that the Air Force only failed to submit 14% of the requisite fingerprint cards and dispositions in the two years measured — a major improvement over the 39% of fingerprint cards and half of disposition reports that went unsubmitted to the FBI during a two-year period between 2010 and 2012.

But the Air Force’s recent improvement is lonely silver lining in an otherwise concerning report: The Army, Navy and Marine Corps all failed to submit more than a quarter of the required offender fingerprint cards and missed submitting about 4 out of 10 of the requisite disposition reports on their criminals. The audit indicates that the Navy’s security forces had the worst reporting gaps, failing to share three-fourths of the required fingerprint cards and disposition reports; the Army’s military police fared only slightly better on both counts.

Military Services Law Enforcement Organizations (LEOs) submission records for fingerprint cards and final disposition reports for service members convicted by court-martial of qualifying offenses between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2016, as collected and analyzed by the Department of Defense Inspector GeneralPhoto via DoD IG

But the Air Force’s recent improvement is lonely silver lining in an otherwise concerning report: The Army, Navy and Marine Corps all failed to submit more than a quarter of the required offender fingerprint cards, and missed submitting about 4 out of 10 of the requisite disposition reports on their criminals. The audit indicates that the Navy’s security forces had the worst reporting gaps, failing to share three-fourths of the required fingerprint cards and disposition reports; the Army’s military police fared only slightly better on both counts.

In response to the Sutherland Springs massacre, the Pentagon has been pushing to fill the holes in its reporting structure, overhauling its criminal background-check procedures and new practices — like the vaguely embarrassing mandate that Air Force investigators “confirm that reportable cases have been entered into the federal database by seeing either a printout or a screenshot from the database,” as the New York Times reported on Nov. 28.

Related: Air Force Admits Its Failure To Report Texas Church Shooter Was ‘Not An Isolated Incident’ »

But the Pentagon IG audit goes farther, recommending that every military branch run a “comprehensive review” to ensure that “all fingerprint cards and final disposition reports for anyone investigated for, or convicted of, qualifying offenses” ended up in FBI hands stretching all the way back to December 1998 — when the DOD’s federal criminal reporting guidelines first went into effect.

And if those files haven’t been reported? Well, per the DoD IG, stop fucking around, find ‘em, and get ‘em into FBI hands yesterday. That means the Army, Navy, Marines, and Air Force have to turn up a combined 601 fingerprint cards and 780 disposition reports spanning two decades to guarantee that, if another Devin Patrick Kelley is quietly plotting a bloodbath out there somewhere, federal law enforcement can identify him and at least keep him from walking out of a local gunshop with the tools to do it.

Read the full DoD IG report:

Evaluation of Fingerprint Card and Final Disposition Report Submissions by Military Service Law Enforcement… by Jared Keller on Scribd

WATCH NEXT: