Including Women Is Not The Right Next Step For Selective Service

Secretary of Defense Ash Carter’s decision to open combat jobs to women caused a lot of controversy among the veterans...

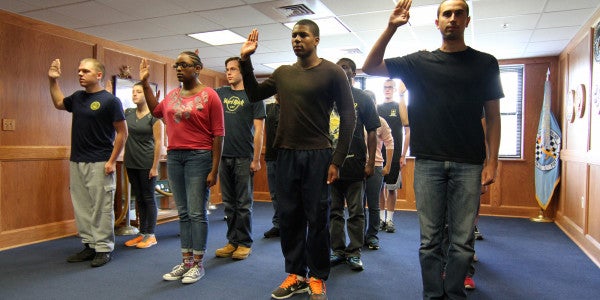

Secretary of Defense Ash Carter’s decision to open combat jobs to women caused a lot of controversy among the veterans community and the public at large. Whatever the merits of that decision, the controversy over it hadn’t even subsided before another one started. Now that women were going to be allowed into all direct combat roles, people started to call for them to be included in Selective Service registration.

That’s a seemingly logical next step. After all, if we accept the premise that men and women are both capable of filling any job in the military, then logically, both should be required to register for Selective Service.

But that’s not seeing the forest for the trees. The easier and better way to achieve gender equality in regard to Selective Service is not to expand it to include women. It’s to acknowledge reality and admit that the Selective Service system is an antiquated relic of a bygone era, put it out of its misery, and eliminate it for all Americans.

The system has been in its current form since 1980 and has never been used once. That’s in spite of two major wars in Iraq during that time, another in Afghanistan, and a plethora of other ongoing combat operations spanning over fourteen years now. Clearly, this nation has demonstrated its ability to fight both conventional conflicts and counterinsurgencies without a draft. What problems we’ve had with those efforts were a result of poor leadership, not a lack of warm bodies.

Defenders of the Selective Service system occasionally remark about a potential existential fight against the Chinese, the Russians, or some other hypothetical threat that could spontaneously spring up. Such people not only ignore the geopolitical questions of how and why this would happen, but also the advantages the U.S. would already have in such fights. More importantly, advocates of the draft always brush over the critical “how draftees would help” part of this scenario.

War is a different business than it was only a generation ago. The technical and training requirements have jumped significantly, even for jobs laymen don’t regard as sophisticated. Being an infantryman is no longer as simple as being handled a rifle and being told what direction to shoot. That’s true for all the other combat arms roles as well. The support specialties that make the tip of the spear so sharp often take even more training.

Military training facilities often have problems getting even today’s relatively small numbers of troops through in a timely fashion. This system would likely collapse under the weight of tens or hundreds of thousands of conscripts that a draft would produce. The Selective Service is supposed to provide new recruits to the military 193 days after activation. Does anyone think the military could muster the resources to conduct proper advanced, or even basic, training for thousands of conscripts in that time? Once it finally did, it would be another several months at minimum before those troops were ready to deploy.

New platoons, battalions, and divisions don’t just appear because the soldiers show up with rifles. They need NCOs and officers to lead them, headquarters and communications to control them, and vast amounts of heavy equipment and supplies to support and sustain them. That’s not even including the dollar costs of keeping a human wave of troops in the field. It can cost upwards of $2 million per soldier to support each deployed soldier in a combat theater. These things don’t magically spring into existence just because draft notices go in the mail.

It’s even more difficult to rapidly expand services like the Navy or Air Force. For example, It takes eight years to build a new aircraft carrier. Without ships to put them on, having more sailors available isn’t very helpful.

The draft is like having an enormous fire truck parked a hundred miles from any house — any emergency severe enough to actually need it will likely be over by the time it actually gets there. Any potential high-intensity existential conflict will be long over by the time draftees could ever reach it — that’s why it’s called a high-intensity conflict. Prolonged low-intensity conflicts are best handled under the existing volunteer force.

That’s not to mention the fact that pulling the trigger on a draft would shoot the existing high-caliber volunteer force in the head. How would volunteers work alongside conscripts? It’s hard enough to maintain discipline among those who actually want to be there, much less forced laborers. Forty years ago, it was acceptable to treat troops with a much harsher (read physical) manner. Today, you’d need new set of brigs to hold all the draftees telling their noncommissioned officers to go perform a sexual act on themselves after being told to field day their barracks.

Then there’s the turmoil it would bring upon pay and benefits. Our pay and benefits system has been built up over 35 years to recruit and retain volunteers. Would draftees be paid less and receive fewer benefits than volunteers? If so, how would it not breed discord between volunteers and draftees? If not, how could the country afford to keep that many people under arms?

On social media, you’ll often hear vets bemoan the supposed low quality of today’s youth and muse about how they should be forced to toughen up in the military for a spell. On the other side of the spectrum, one sometimes hears about how the volunteer force unfairly exploits the poor and disadvantaged. While these premises are dubious to begin with, the result of each is the same — using the military for something other than its intended mission.

The military’s mission is “to provide the military forces needed to deter war and to protect the security of our country.” It’s not to toughen up our youth or correct social injustice in America. If you think today’s youth are getting off on the wrong foot, look at changing the education system. If you think the poor need better options to pay for school than joining the military, then work to make more scholarships available.

While the inclusion of women in direct combat roles is a separate issue, it has given us an opening to look at a lot of other things that should have been fixed long ago. For instance, we’re now finally creating objective job-related physical standards. Another thing this gives the opportunity to fix is maintaining the dubious fantasy that the U.S. will ever return to a draft. Rather than double down on the Selective Service mistake by including women, let’s use this opportunity to stop lying to ourselves.