404

Sorry, we couldn't find the page you were looking for.

Click the "back" button in your browser or choose from a few options below to get back on track.

Or take a look at these articles we think you may like

Military daycares could partner with off-base facilities, hire more workers under new bill

Gold Star fraudster targeted women, non-English speakers and those with little financial literacy

Oklahoma considers offering veteran discount at liquor stores

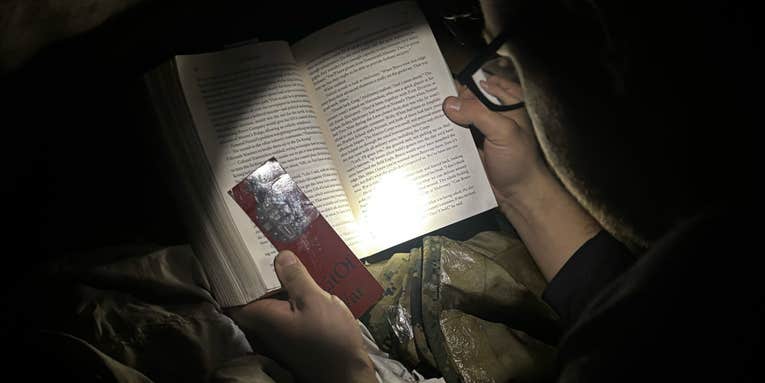

Two Marines are out to bring ‘literature of war’ to foxholes

Inside the changing world of drone warfare

Supreme Court sides with Army veteran in overlapping GI Bill benefits case

Veterans sentenced to prison for scheme that bilked TRICARE for $65 million

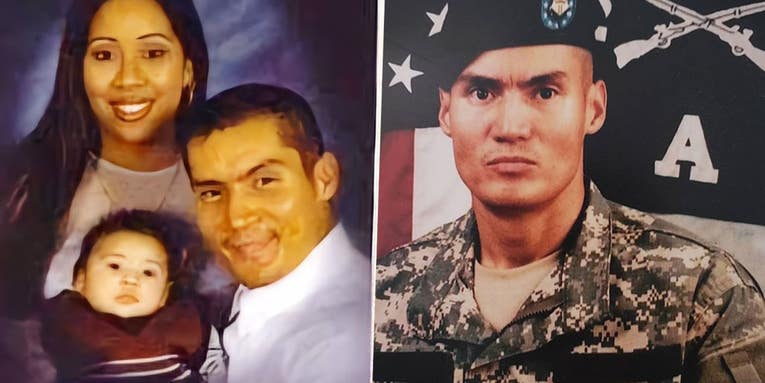

Army Reservist admits he scammed $10 million from Gold Star families

Special Forces engineers are training to dig ditches and destroy tanks

Married Army couple win back-to-back Sapper school awards

This is why Marines were at Mar-a-Lago