How the US suffered 300 casualties storming an empty island in WWII

The Aleutian Island campaign during WWII saw heavy fighting between US and Japanese forces, but Kiska island was a different story

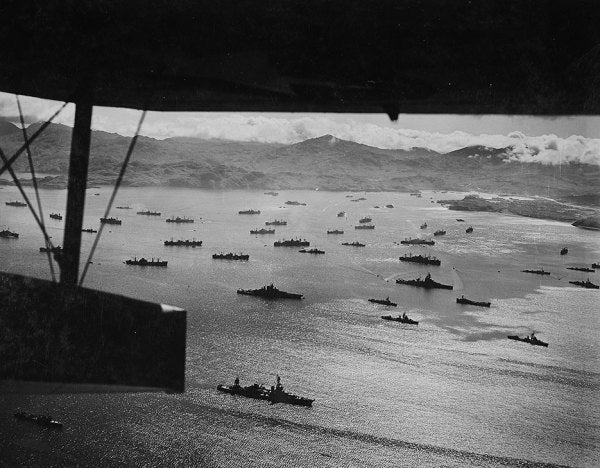

On Aug. 15, 1943, a massive Allied force assaulted a North Pacific island at the height of World War II. A joint force of 34,000 American and Canadian troops, supported by warplanes and naval bombardment, moved inland through frigid and unforgiving terrain searching for occupying Japanese forces.

By the end of the second day, 300 Allied soldiers lay dead or wounded. However, there wasn’t a Japanese soldier in sight. The island had been evacuated three weeks prior. It was completely deserted.

Called Operation Cottage, the goal of the amphibious assault was to retake the small volcanic island of Kiska, one of 14 that make up Alaska’s Aleutian islands, from Japan. Ahead of the attack, the Allies shelled and bombed Kiska island, but on July 28, a small Japanese task force penetrated the blockade under the cover of heavy fog and extracted more than 5,000 Japanese soldiers from the small volcanic island in less than an hour.

So how then, did an unopposed amphibious assault result in hundreds of casualties?

On Aug. 18, the Navy destroyer Amner Read struck a mine in Kiska Harbor, killing 70 sailors and wounding 47 more, according to Del Kostka who has written extensively about the Aleutian Island Campaign. Other casualties occurred due to friendly fire, vehicle accidents, landmines, and booby traps. In total, Operation Cottage resulted in 92 deaths and a further 221 wounded, some grievously.

Related: This WWII Naval Ship Was So Unlucky, It Almost Killed FDR »

To understand what happened on Kiska island it’s important to look back to May of that year when Allied forces launched an amphibious assault against another Japanese stronghold on a different Aleutian Island called Attu.

Caption: A U.S. Army image depicting the territory under Japanese military control during World War II.

On May 10, 1943, Operation Landcrab was set in motion. Allied forces assaulted Attu island, where the Japanese were hurriedly building an airfield to serve as a buffer between U.S. forces and mainland Japan.

The mission was to retake Attu from the occupying forces, and though it was ultimately successful, of the 16,000 Allied troops fighting on Attu, 3,829 became casualties, including 549 killed in action. Of the 2,650 Japanese soldiers stationed on Attu, all but 29 fought to the death, notes Kostka whose father served as an engineer during the battle to take Attu.

It was with the battle for Attu in mind that so many troops were ordered to retake Kiska, the last enemy stronghold on North American soil, which the Japanese had held since June 7, 1942. The allies expected to encounter an entrenched enemy force, one which had proved time and time again that every foot of ground gained would cost numerous lives.

“I think the biggest takeaway is not to always trust everything you see,” said Kostka of Operation Cottage in an interview with Task & Purpose. “Sometimes, appearances can be deceptive, and our own personal bias can kind of lead us astray when it comes to interpreting the motivation and the predictive course of action of others.”

American military brass anticipated that the Japanese defenders would retreat inland where they could fire with impunity on the landing parties, as they had on Attu, even though reconnaissance reports showed no enemy activity on the island leading up to the amphibious assault.

“That the Allied staff might have had an unrealistic impression of Japanese resilience and fortitude in August 1943 is understandable given the context of prior events in the Pacific,” wrote Kostka. “Japan’s samurai heritage and code of ethics known as bushido fueled a stereotype of a warrior culture steeped in obedience, discipline, and staunch revulsion to surrender. The intensity and savagery of the fighting on Attu only served to reinforce this image.”

Though the fight for Attu certainly informed the decisions of Allied commanders, it also had an effect on the Japan’s military leaders, who did not wish to see a repeat of Attu on Kiska.

“The decision to evacuate the Kiska garrison was not taken lightly,” Kostka wrote. “But even the most aggressive Japanese commanders realized that Japan’s hold on Kiska was pointless, and manpower was badly needed elsewhere in the Pacific.”

By the time the Allied forces attacked Kiska in full force on Aug. 15, the island was empty, with the exception of a few stray dogs. Though Kiska was ultimately recaptured it came at great cost and serves as a cautionary tale of the effects of perception and assumption explained Kostka. It also serves to show that no military operation is ever without risk.