Why The OODA Loop Is Forever

John Boyd forever changed the way the United States fights wars, both on the ground and in the air. This...

John Boyd forever changed the way the United States fights wars, both on the ground and in the air. This is rather impressive considering his own limited battlefield experience, as he just missed World War II and barely caught the end of the Korean War.

He prompted us to think differently about war. He first changed the way aircraft designers and pilots thought about aerial combat when he developed the energy-maneuverability concept with his friend Tom Christie.

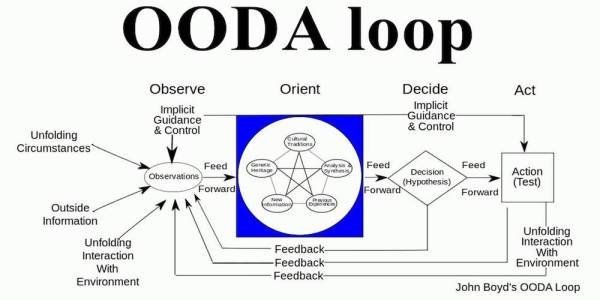

He then extrapolated that concept out into a cohesive theory of warfare following an exhaustive interdisciplinary study of physics, mathematics, history, psychology, anthropology, and any number of other subjects. The OODA loop became just one of many important contributions to the body of work that produced Maneuver Warfare doctrine.

To understand the OODA loop, it is important to first understand what it isn’t. Contrary to conventional wisdom, the OODA loop is not synonymous with decision-making. While individuals process information in an OODA-like fashion preparatory to making a decision, it’s the last letter in the acronym that deserves the most attention.

OODA is an action cycle. More importantly, it is the action cycle of a system, not a person.

To chart John Boyd’s development of the concept, let’s begin where he did—in the cockpit of an F-86 Sabre. Boyd and the other fighter pilots flying against the Soviet-made MiG-15s were surprised to see how much better their aircraft performed. The MiG could fly faster, higher, and turn better than the Sabre, yet the Americans shot them down at a rate of 8:1.

These lopsided results prompted Boyd to study how they were achieved. He determined the F-86 had several subtle performance characteristics that offset the MiG’s traditional objective performance advantages. The two most important were the F-86’s high bubble canopy and its fully hydraulic flight control system. The Sabre pilots had a superior view of the battlespace and could transition between maneuvers faster, as the MiG had poor all-around visibility and its mechanical flight controls meant pilots could not shift maneuvers as quickly.

F-86 pilots did not operate as individuals, but as part of a system with their aircraft. The bubble canopy helped them to use their eyeballs to gain a greater level of situational awareness, and the hydraulics allowed them act quicker which tightened their “loop.”

Related: I’m So Sick Of The OODA Loop »

Taking this system’s view of the OODA loop, the true vision of John Boyd begins to emerge. The concept now applies to every level of military command, from a fire team through a field army. It is possible to see how the Marine walking point on a patrol observes a threat and communicates that back to the squad leader. The squad leader then orients his unit to the developing situation, makes a decision about the proper response, and then comes the sine qua non—implementation of the action.

The real value of John Boyd’s idea now comes into clearer focus. That squad is made up of three fire teams, each with their own OODA loop. The squad is one of three in a platoon, and the platoon is one of four in a Marine rifle company. Each echelon of this command has its own OODA loop made up of an expanding number of subordinate interdependent OODA loops down through the chain.

When you understand the concept in this way, you start to see why it is important to optimize each one of these OODA loops. Friction now becomes any factor that slows down an OODA loop. When we load down an infantryman with an extra piece of gear that ends up slowing their response time, every unit above will be affected.

In this light, Boyd’s concept of the OODA loop should be used to filter decisions about education, organization, and even equipment. For example, the Army’s newest tank upgrade adds weight and decreases fuel capacity. This will require tank units to refuel more often and potentially expand the logistics footprint. These factors induce extra friction which ultimately slows down the overall force’s OODA loop.

Just because people misuse a term doesn’t mean the original concept has no value. Rather than throwing out the proverbial baby with the bathwater, people should redouble their efforts to understand what John Boyd actually meant, not just what popular culture says John Boyd meant.

Dan Grazier is a fellow with the Center for Defense Information. He spent 10 years as a Marine tank officer. He is a graduate of Virginia Commonwealth University and is currently working towards a Master of Arts in military history at Norwich University. He tweets at @dan_grazier