Congress is set to finally rescind the authorizations for use of force that served as the legal basis for the Persian Gulf and Iraq wars, but in terms of reining in the president’s abilities to send U.S. troops into combat at will, here’s what’s likely to change: Nothing.

On Sunday, lawmakers released the final version of the Fiscal Year 2026 National Authorization Act, an annual defense policy bill, which would officially revoke the authorizations for use of military force in 1991 and 2002 that Congress passed prior to both wars in Iraq. The Senate and the House of Representatives must now vote to pass the legislation.

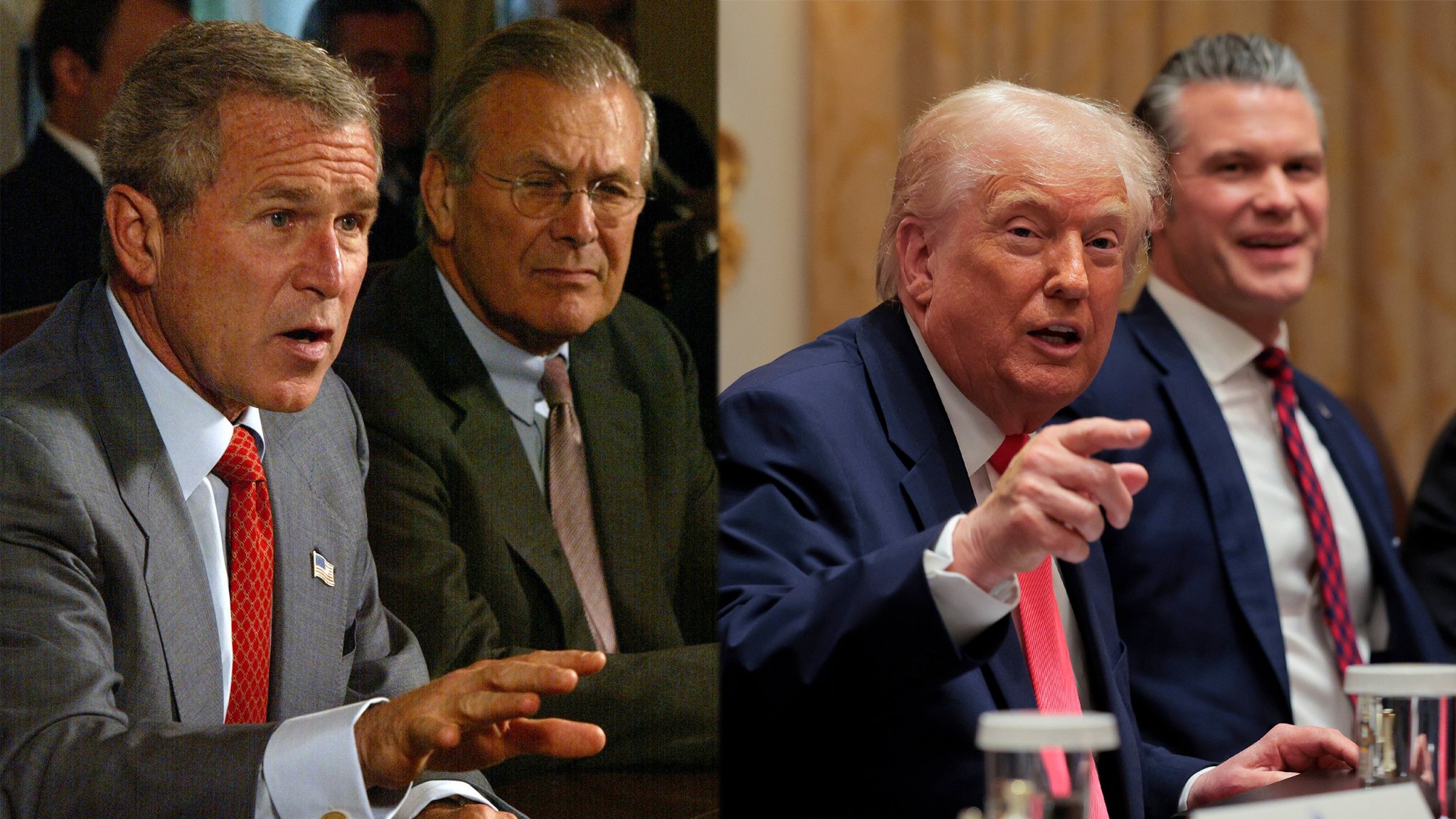

However, the far more sweeping authorization passed shortly after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks that has served as the Global War on Terror’s legal basis for more than two decades remains on the books. The authorization has far outlasted President George W. Bush’s administration, and it has been repeatedly used by presidents of both parties in the years since.

When Congress empowered the president to strike back at any country, group, or person involved with the attacks “to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States,” it opened the door to military operations beyond the legislation’s original intention. Presidents have cited that authorization as the legal justification for airstrikes against the Islamic State group in Iraq, Syria, and Libya.

Top Stories This Week

The executive branch’s power to wage war against terrorist groups has become especially relevant since the U.S. military began destroying boats in the Caribbean and Pacific suspected of carrying drugs earlier this year. These operations came after the State Department designated several drug cartels as terrorist organizations.

U.S. government officials have consistently referred to the alleged drug smugglers targeted in military strikes as “narco-terrorists,” underscoring that the war on drugs has morphed into the sequel to the War on Terror.

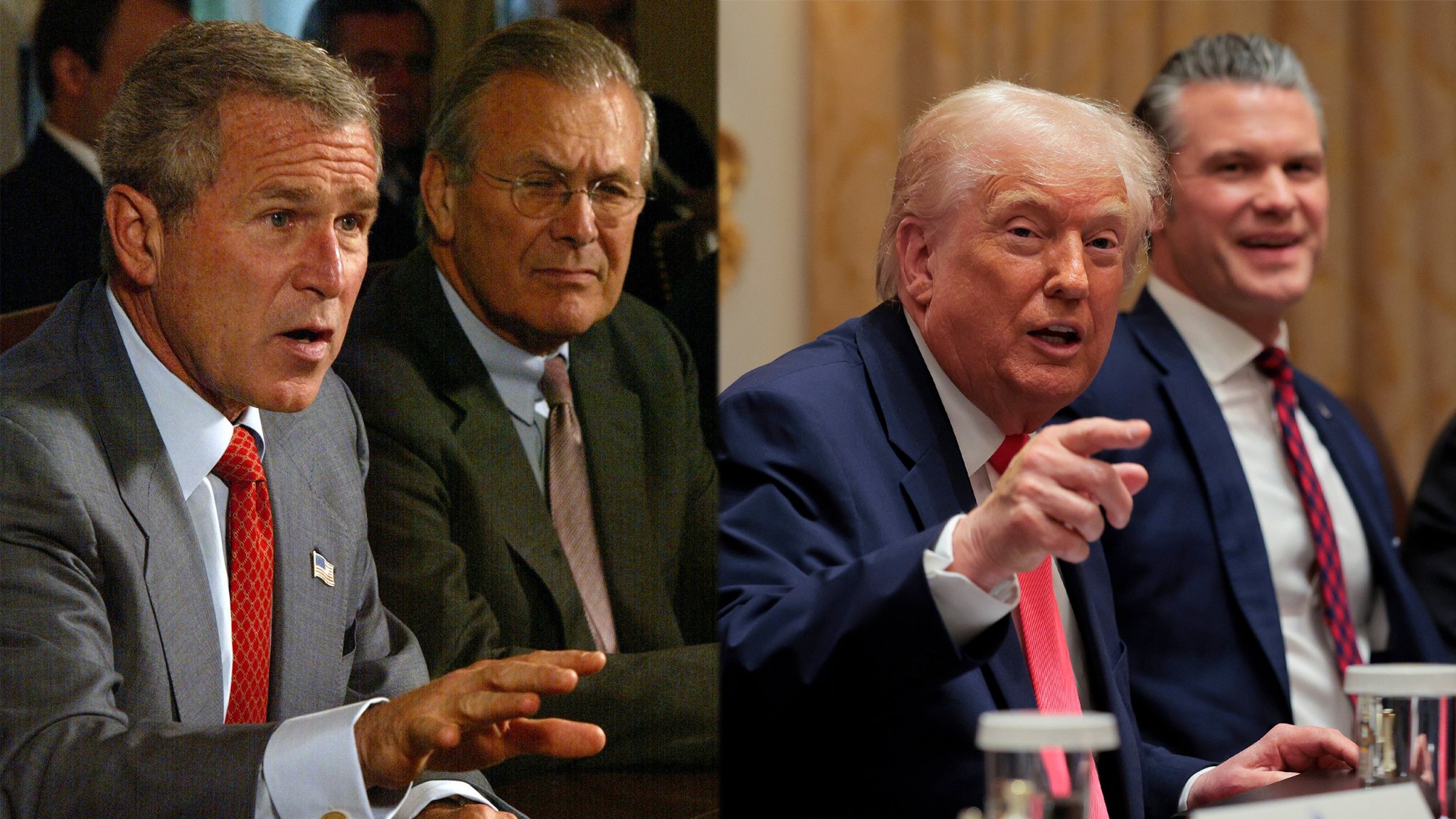

In September, shortly after the first strike on a suspected drug boat, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth claimed to reporters that “A drug cartel is no different than al-Qaida.”

A White House official also told Task & Purpose on Monday that each strike targeted vessels that the U.S. intelligence community had determined to be affiliated with a designated terrorist organization that was trafficking drugs that could kill Americans. In October, the Trump administration told Congress that it considered the United States to be in an “armed conflict” with drug cartels.

Chances are slim to none that Congress will rescind the 2001 authorization any time soon, especially since it has taken lawmakers many years and several failed attempts to revoke the 1991 and 2002 authorizations for both Iraq wars — the latter of which was used to justify the January 2020 U.S. airstrike that killed Iranian Maj. Gen. Qasem Soleimani, head of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Quds Force.

But even without the 2001 authorization, presidents have cited other legal justifications for military strikes in “self defense,” such as Article 51 of the United Nations Charter and Article II of the Constitution.

As the world waits to see if the U.S. military will launch strikes inside Venezuela, the legality of the strikes has come under some scrutiny, though it’s largely focused on individual strikes rather than the overarching legal framework used to justify them.

Of the strikes, the White House official said that “lawyers up and down the chain of command are thoroughly involved in reviewing the proposed operations prior to execution.”

Congress has shown it is either unwilling or unable to stop presidents from waging war after a conflict has started, as evidenced by lawmakers’ failed efforts to cut off funding for the Iraq War. In June 1973, lawmakers voted to ban funding for operations in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, but that was nearly five months after a ceasefire that effectively ended the U.S. military’s involvement in the Vietnam War.

Meanwhile, the pending repeal of the Iraq War resolutions will not mean the end of the U.S.-led war against the Islamic State group, or ISIS, even as the United States reduces its footprint in Iraq. In October, Iraq’s prime minister said that at least 250 Americans would remain at the Al-Asad Air Base, a reversal of plans for a full withdrawal. American forces continue to work with Iraqi security forces to fight ISIS militants inside the country, as it also does with partners in Syria.