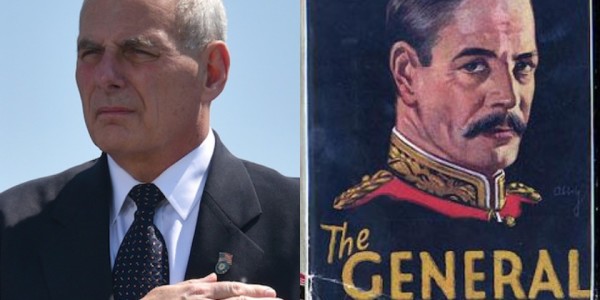

When then-Secretary of Homeland Security John Kelly was tapped to serve as the new White House Chief of Staff, much was made of Kelly’s favorite novel, The General, by C.S. Forester. Kelly himself noted that he read the book each time he was promoted during his career in the Marines. Written in 1936, The General tells the story of General Sir Howard Curzon, a competent and ordinary British cavalry officer. Curzon rises through the ranks as the story progresses, owing his successes to sheer opportunism, bureaucratic know-how, attrition from combat, and dumb luck rather than any kind of professional or personal development. What worked for him as an inexperienced subaltern during the Boer War is all he brings to his eventual Corps command in World War One.

Kelly has stated his main takeaway from The General is the importance of critical thinking. Especially at different points in one’s career. C.S.Forester used the character of Howard Curzon to criticize the generation of British Generals who commanded the troops going Over the Top in World War One. As historian Max Hastings points out in his introduction to the most recent edition of the novel, this technique fits squarely with the criticisms of movement launched by British veterans of World War I. B.H. Liddell Hart, among others, argued that there might have been alternatives to the slaughter of the Western Front, if only the General Staff had shown more intellectual curiosity to the military situation at hand and paid less heed to the traditions of the old army. While the historiography of World War One has grown more complex, the portrayal of Curzon as an honest but stale leader has stood the test of time.

So what has Kelly learned from The General? Oddly enough, a scene from the novel almost identically played out during Kelly’s time as deputy commander to James Mattis during the Iraq War.

After throwing his ill-begotten division into the buzz saw of the Somme, Major General Curzon is overseeing the defense against a German attack upon his sector. The brigade taking the brunt of the assault holds a salient. The brigade’s commander, a Brigadier General named Webb, phones Curzon, requesting permission to withdraw a few hundred yards to a more defensible position. Curzon is disgusted. Despite Webb’s reasoning that the situation he is experiencing on the ground differs from Headquarters’ expectations, thus necessitating a change that can improve his tactical situation without compromising the overall situation, Curzon won’t allow it. The spirit of the offensive lies at the heart of the army’s identity. A retreat was not only in defiance of doctrine; it was unmanly, a sign of moral weakness. By broaching the subject of withdrawal, Curzon deems Webb unworthy of serving in his division. No better than the “free thinkers” on his staff who bother him with airplanes, tanks, and other new technologies. General Curzon provides no professional reason why the brigade should remain in the salient. He simply dismisses General Webb in the midst of the fighting.

The General was written as an allegory demonstrating the perils of the failure to ask questions and challenge one’s own cherished assumptions. For Kelly, this was the reason for the novel’s prominent place on his professional reading list.

What has John Kelly learned about himself and his new position after reading the novel upon each promotion? Especially his last one.

Kyle Gaffney received his master’s degree from William Paterson University. His work has appeared in The Strategy Bridge and Task & Purpose. He lives in New Jersey with his family. His tweets at @citizenGaffney