Why America’s first bomber was called ‘the flaming coffin’

American airpower had to start somewhere

Budget day is right around the corner, which means members of Congress and the media will get to shake their heads disapprovingly at the Pentagon’s request for oodles of money for problem-ridden aircraft such as the F-35 Lightning II, which the last acting secretary of defense called a ‘piece of [expletive deleted]’ and the KC-46, an aerial refueling tanker which is already years behind schedule and has a leaky toilet, among other problems.

But these vehicles are far from the first screwy aircraft that Uncle Sam’s shelled out for. In fact, the first American-built bomber in history was such a hot mess that it earned the nickname “The Flaming Coffin.”

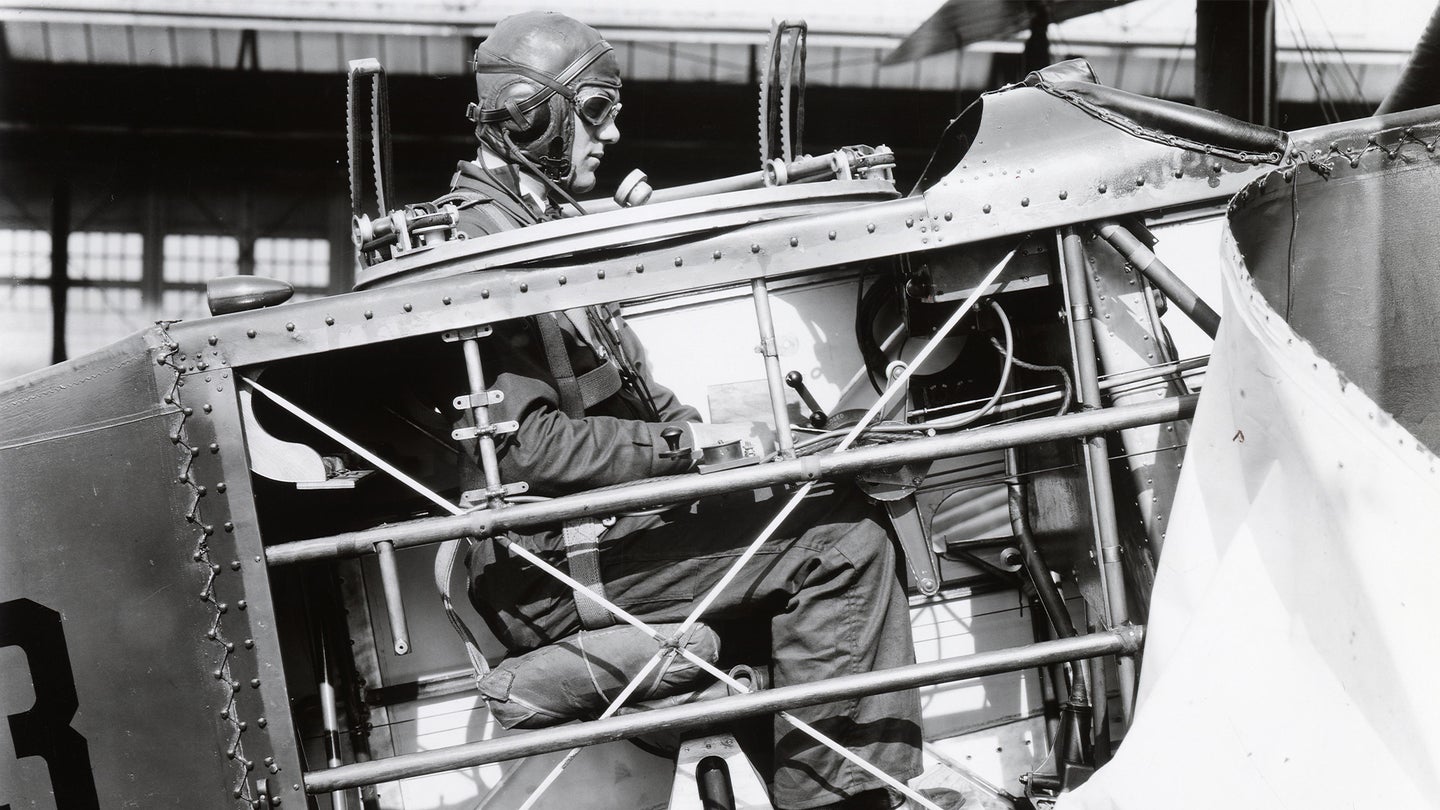

What was this notorious aircraft? The De Havilland DH-4 biplane, also called the “Liberty Plane.” Based on a combat-tested British design, the DH-4 was the only American-built aircraft to see combat during World War I, and it was the aircraft that turned the U.S. Army Air Service from a haphazard gaggle to a robust program which produced battlefield results, according to a recent press release from the Kentucky National Guard.

But its beginnings were far less grand. The DH-4’s pressurized gas tank had a tendency to explode, and a rubber fuel line connected to the engine had a habit of causing fires, according to an Air Force profile of the aircraft. For context, the biplane was made out of a spruce wood frame covered with fabric, so fires aboard the aircraft were disastrous. The gas tank was also located right between the pilot and the backseat observer, which made mid-flight communication between the two nearly impossible. The gas tank could crush the pilot in an accident and, worst of all, it presented a juicy target for enemy gunners.

Despite the danger, the nickname “Flaming Coffin” might not have been deserved: only eight of the 33 DH-4s lost in combat by the U.S. burned as they fell, according to the Air Force. The Army put the Liberty to good use, deploying it for daytime bombing, observation and artillery spotting missions. The DH-4 also earned its stripes as a fighter when Marine Corps 2nd Lt. Ralph Talbot and Gunnery Sgt. Robert Robinson went head-to-head with 12 German fighters while flying the DH-4 during a bombing raid over Belgium on Oct. 8, 1918. The two men were awarded the Medal of Honor for their heroics.

The Liberty’s most notable mission was in October 1918, when Army 1st Lt. Harold Goettler and 2nd Lt. Erwin Bleckley of the 50th Aero Squadron were shot down trying to resupply some 500 soldiers of the famed “Lost Battalion,” which was cut off and surrounded by German forces in the Argonne forest. Both men were posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for their efforts.

The quantity and quality of the planes improved as the war went on, so that they became the basis of the Army Air Service’s fleet of combat-ready aircraft, according to the National Park Service. The two-seater aircraft could fly up to 128 miles per hour, had a range of 400 miles, sported two .30 machine guns in the nose and the rear, and could carry 322 pounds of bombs. But here’s a story about questionable use of military assets: by the end of the war, there were 1,213 Liberty planes in France, but there were so many improved DH-4Bs being produced in the U.S. and shipping costs were so high that it did not make sense to ship the older aircraft back across the Atlantic. Instead, they burned it all in what became known as the “Billion Dollar Bonfire.”

The defense budget shrank dramatically after the end of the war, so the Army continued to use the DH-4 in peacetime roles as a transport, air ambulance, photographic plane, trainer, target tug, forest fire patroller, and even as an air racer, according to the Air Force. The U.S. Post Office also operated the DH-4 as a mail carrier. In the 1920s, the Liberty was used to test new airplane technology such as turbo superchargers, propellers, landing lights, engines, radiators and weapons.

The DH-4 helped fight bandits on the border with Mexico in 1919; flew from New York to Nome, Alaska in 1920; was flown by the legendary Jimmy Doolittle (commander of the famous Doolittle Raid) in a record-breaking cross-country trip from Jacksonville, Florida to San Diego, California in 1922; and executed the first successful air-to-air refueling in 1923. By the time the DH-4 was retired in 1932, the humble little plane had been developed into over 60 variants, according to the Air Force.

If the “Flaming Coffin” can make good, maybe there’s hope for the F-35 and KC-46 after all.

Featured image: Fabric of DH-4M peeled away from gunner’s seat to show new steel tube fuselage. (National Museum of the U.S. Air Force photo)

Related: ‘You are the reason I drink’ — Airmen bid adieu to decrepit aircraft dubbed ‘Lucifer’s Chariot’