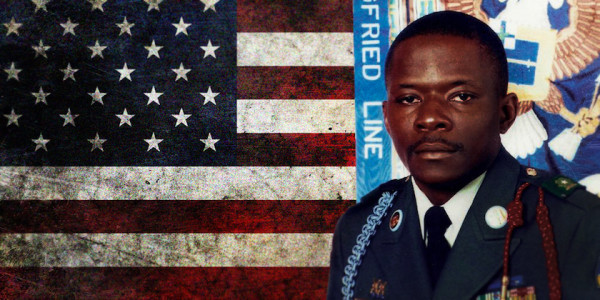

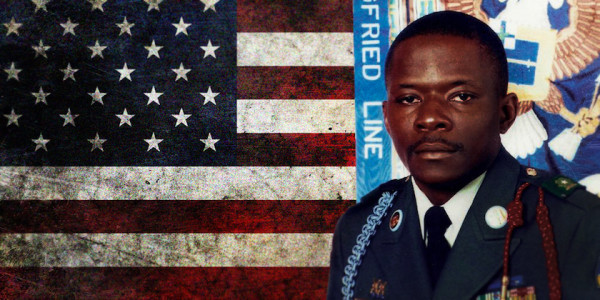

Three. That’s how many times Sgt. 1st Class Alwyn C. Cashe entered the burning carcass of his Bradley Fighting Vehicle after it struck an improvised explosive device in the Iraqi province of Salahuddin on Oct. 17, 2005. Cashe, a 35-year-old Gulf War vet on his second combat deployment to Iraq since the 2003 invasion, had been in the gun turret when the IED went off below the vehicle, immediately killing the squad’s translator and rupturing the fuel cell. By the time the Bradley rolled to a stop, it was fully engulfed in flames. The crackle of incoming gunfire followed. It was a complex ambush.

Slightly injured and soaked in fuel, Cashe scrambled down into the hull and extracted the driver, who was on fire. After putting out the flames, Cashe returned to the vehicle, at which point he, too, caught fire. One of the six soldiers in the payload compartment managed to lower the back ramp, revealing the inferno inside. By the time he got every soldier out of the Bradley alive, Cashe was the most severely wounded. According to this Silver Star citation, 72% of his body was covered in second and third-degree burns, but he insisted on being the last man on the medevac bird. Later, people who knew Cashe would say that’s just the sort of non-commissioned officer he was — selfless, tough as nails, old school. He always put his soldiers first.

“Sgt. Cashe saved my life,” Gary Mills, who was inside the burning Bradley, told Los Angeles Times in 2011. “With all the ammo inside that vehicle, and all those flames, we’d have been dead in another minute or two.”

If the military scrutinizes the evidence and ultimately rejects Cashe’s nomination, it should provide his supporters with “incontestable proof” that he did not earn the Medal of Honor.

Cashe died on Nov. 8, 2005, at the Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas. Those who were with him on his deathbed say he never stopped asking about his soldiers, four of whom ultimately died. Cashe was awarded the Silver Star posthumously for his actions. The medal had been recommended by his battalion commander, then-Col. Gary M Brito. Eventually, however, Brito came to realize that he had made a mistake. After learning more specific details of Cashe’s actions that day, and that he had done it all while being shot at, Brito launched a campaign to have his Silver Star upgraded to the Medal of Honor. The nomination was submitted to the Army in May 2011. It hasn’t been heard from since.

It takes a lot more than just extraordinary courage under fire to attain the Medal of Honor. The heroic act is the first of many monumental steps that must be taken before a service member is deemed worthy of the nation’s highest award for combat valor. The success or failure of a Medal of Honor recommendation hinges less on the act itself than on how the story is told through the witness statements, after-action reports, news articles, and whatever other evidence is included in the nomination package. It is the only military medal that requires “incontestable proof of the performance of the meritorious conduct,” and also the only one that must be approved by the president on behalf of Congress. But to reach the Oval Office, a nomination package must first travel through a vast bureaucratic labyrinth, undergoing numerous reviews and revisions along the way. A lot of signatures are necessary. Myriad known and unknown factors influence the length of the recommendation process, which begins at the battalion level and ends on the desk of the secretary of defense. According to the Army, it “can take in excess of 18 months with intense scrutiny every step of the way.” That’s a euphemistic way of saying that it can take a very, very long time. Even cases that seem open and shut have a way of, well, just disappearing.

Army image

Take, for example, the case of Cpl. David D. White, who served with the 37th Massachusetts Regiment in the Civil War. Soldiers who fought alongside White in the Battle of Sailor’s Creek near Farmville, Virginia, credited him with capturing Maj. Gen. George Washington Custis Lee, the eldest son of Gen. Robert E. Lee. The government deemed it a Medal of Honor-worthy act — in part because it occurred amid one of the most decisive and brutal battles of the war — but White was never awarded the medal. Instead, it went to another Sailor’s Creek veteran: Cpl. Harris S. Hawthorne of the 121st New York Infantry, who allegedly refused to return the medal to the War Department after an investigation prompted by protests from White’s furious comrades discovered that key details of his story didn’t add up.

More than a century later, White’s great-great-grandson, Frank E. White, of Clinton, New Jersey, picked up the fight to set the record straight. White compiled decades of research on the controversy into a book he authored in 2008. He and his family then submitted a nomination for his ancestor to receive the Medal of Honor in 2011. Eventually, after years playing bureaucratic ping-pong with the Army, the family enlisted the aid of several influential lawmakers, who penned a July 2014 letter recommending that White receive the Medal of Honor. But the Army still refused to reopen the case. It was only after a review by the Defense Department inspector general’s office concluded that the case hadn’t been properly handled that Army Secretary Mark T. Esper directed the Senior Army Decorations Board to look at it again — as “an act of prudence,” the Washington Post reported in December.

Many would argue that the White family’s Kafkaesque saga is an example of the military award system operating exactly how it’s supposed to. They’d applaud the bureaucrats for guarding the Medal of Honor like sentries, ready to rip apart any nomination that approaches the fortress gates. After all, the medal has no intrinsic value. You can’t use it to, say, chop lumber or feed your family. The medal’s value is solely derived from the notion that only the very best of the best are capable of attaining it. Handing out Medals of Honor willy-nilly would result in inflation. Which is not to say that it doesn’t serve a significant practical function: Soldiers in combat draw courage from the belief that if they die going above and beyond the call of duty, their final heroic act will be enshrined in public memory.

Sgt. 1st Class Alwyn Cashe, in an undated photo.Courtesy photo

With that in mind, it makes perfect sense why the military would resist calls to crack open old Medal of Honor cases. To acknowledge that mistakes were made — even if they were made more than century ago — is to also concede that the award system isn’t perfect. But of course it’s imperfect. There’s no scientific method for measuring valor. The best we can do is establish and enforce criteria to make the evaluation less subjective. For example, Congress mandates that to earn the Distinguished Service Cross — the Army’s second-highest valor award — a soldier in combat must distinguish themselves “by extraordinary heroism not justifying the award of a Medal of Honor,” and “the act or acts of heroism must have been so notable and have involved risk of life so extraordinary as to set the individual apart from his comrades.”

The Medal of Honor criterion is both the most specific and most rigorously enforced. It’s in a league of its own. To earn one, a service member must “distinguish themselves conspicuously by gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of life above and beyond the call of duty.” Furthermore, the “meritorious conduct must involve great personal bravery or self-sacrifice so conspicuous as to clearly distinguish the individual above his or her comrades and must have involved risk of life.” Perhaps the most perfect example of a Medal of Honor-worthy act is jumping on a grenade. In fact, four of the 18 service members awarded the medal for actions in Iraq and Afghanistan since the onset of the War on Terror jumped on grenades. It is an act of pure humanity performed under the most savage of circumstances. You don’t earn the Medal of Honor by stacking bodies. You earn it by demonstrating a willingness to die so others may live.

So then why hasn’t Cashe been awarded the Medal of Honor? Those who knew him — especially the ones who witnessed the events incompletely described in his Silver Star citation and lived to tell the story — will argue, as they have exhaustively over the past 13 years, that Cashe was the embodiment of everything the medal symbolizes. Just like jumping on a grenade, it is impossible to walk into a furnace thinking you’re not going to die, or, at the very least, be grievously wounded. The skin on your arms and face begins to bubble. The heat sears your eyes. Your lungs spasm. Cashe made that hellish trip three times. And his flesh was still smoldering when he refused to be medevaced until he knew all of his guys had been loaded onto the helicopters.

72% of his body was covered in second and third-degree burns, but he insisted on being the last man on the medevac bird. Later, people who knew Cashe would say that’s just the sort of non-commissioned officer he was — selfless, tough as nails, old school. He always put his soldiers first.

Doing everything possible to ensure that the Medal of Honor never finds itself around the neck of an undeserving recipient is crucial to preserving the integrity of the entire award system. But so is finding out the truth, especially when presented with overwhelming evidence that a service member deserving of the medal was never awarded it. Cashe’s case has been the subject of countless news articles over the years, including at least one that raised the question of whether racism is partly to blame for the Army’s seeming lack of urgency. If Cashe is awarded the Medal of Honor, he’ll be the first African-American of the post-9/11 generation to receive it. The Army’s refusal to discuss the details of his case, or even disclose whether or not it is still under review, only fuels lingering suspicions that the award system is corrupted by politics and prejudice. If the military scrutinizes the evidence and ultimately rejects Cashe’s nomination, it should provide his supporters with “incontestable proof” that he did not earn the Medal of Honor.

(A public affairs officer with the Army’s Human Resources Command told Task & Purpose that his office was not allowed to discuss the case and referred us to the Office of the Secretary Defense, whose PAO then relayed our request back to the Army. We are still awaiting a response and will update this article if and when we receive one.)

When Cashe arrived at the U.S. Air Force Theater Hospital at Balad Air Base in Iraq, he was still fully conscious. Alisha Turner, then an Air Force medic, was part of the team that treated Cashe and three of his wounded comrades. When we spoke recently, Turner called the encounter her “Pandora’s box.” Cashe, she remembered, was the fourth casualty through the door. He was burned badly. What remained of his uniform was melted to his skin. Turner’s team rushed Cashe into the ER, where he started fighting to get off the gurney. “He just kept saying, ‘I’m good, I’m good, take care of my guys,’” Turner said. “He wanted us to focus on everyone else. It was as if they were his children.”

It took about 10 minutes for the medics to calm Cashe down enough to begin working on him. Turner tried to keep track of him on the military’s patient tracking system after he left Balad, but eventually she lost him. Years later, she typed his name into Google and discovered that he had died. She joined a Facebook page devoted to advocating for Cashe to receive the Medal of Honor and shared her story with the group, which was full of other people Cashe had made a strong impression on — not just in Iraq, but throughout his life. “I hope he gets the credit he deserves, because he was remarkable that day,” Turner told me. Then she wept.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this article misstated that Task & Purpose had spoken with a public affairs officer with the Army’s Awards and Decorations Branch. The PAO was, in fact, with the Army’s Human Resources Command. 1/4/2017 11:17 a.m. EST.

WATCH NEXT: