Editor’s Note: This is an opinion column. The thoughts expressed are those of the author.

I glanced in the rearview mirror to see my son fidgeting in his seat. I could see the tension and emotion bubbling up inside his skinny body. Finally, he said it.

“Daddy forgets everything! I bet he doesn’t remember that he is supposed to go to the baseball meeting tonight. Then we’re not gonna know what to do, because you’re making us go to a stupid dentist appointment.”

“He doesn’t forget everything,” I said.

“Yes, he does, unless it’s work. Then he doesn’t forget it.”

I considered what to say. My children are now at an age where they notice things. Gone are their toddler bodies and brains with simple wants and needs, and an even simpler understanding of what’s going on around them. They are upper elementary schoolers, with hawk-like perception.

They notice how often my husband comes back inside for his keys, thinking they were “right there.” Or that he has to go back to the office because he left something on his desk. They notice how much of the calendar I manage, and how many reminders I send him. They have felt the brunt of his forgetfulness, never knowing why.

I wanted to pull the van over and give my oldest a hug, tell him everything would be ok, that he needn’t worry about the baseball meeting. Instead, I told him the truth.

“Remember how we’ve talked about daddy being blown up in Afghanistan?” I asked him.

A sulky, “Yeah,” the only response.

“Well, that’s the reason he forgets.”

Silence.

I glanced again in the rearview mirror to see my oldest chewing on this information. A, “yeah but” was already forming on his lips.

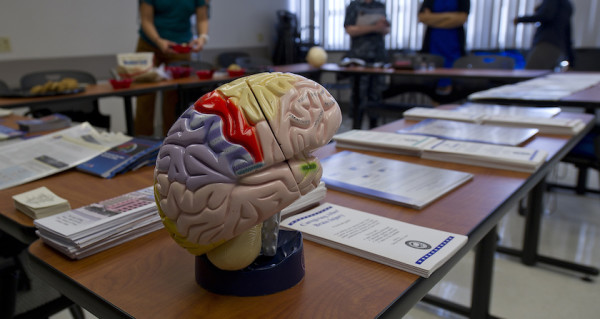

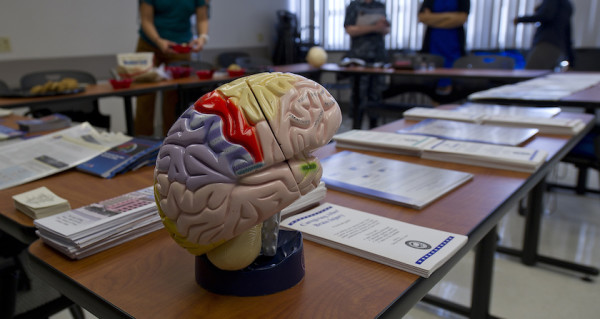

My son didn’t know the full story: From late 2012 through mid-2013, my husband served in western Afghanistan as part of Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) Farah. On April 3, 2013, he was on a foot patrol with two fellow team members and an interpreter when a vehicle-borne IED detonated nearby. At the time, he did not see any physical wounds, but felt a bit “off.” Several days and nights of disorientation and interrupted sleep later, he received medical treatment. It wouldn’t be until much later that he was diagnosed with the “signature wound” of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, a mild traumatic brain injury, which affects more than 400,000 service members.

“That explosion fundamentally changed the way his brain functions,” I said. “You can’t be blown back with that much force without it impacting how your brain works. His brain now has to work extra hard to remember the little stuff, because that explosion changed it.”

He asked me how I knew.

“Because I have the benefit of knowing him before. Y’all were really little both before and after that deployment. There’s no way that you would remember what he was like before. You’ve grown up with the after.”

“Well, that sucks,” he said.

“Yep. It does. And perhaps we can offer Daddy a little more grace on the things he’s forgetful about. Be a helper. Not a constant reminder that he’s forgetful. He’s doing his best.”

A couple of days have passed since that chat with my son. Since then, I’ve had conversations with other military spouses, who have had similar conversations in their homes. The resounding narrative is: It’s tough, as a mom, to watch your children grapple with the effects of war. Trying to both acknowledge their perspective and pain, while simultaneously keeping them from villainizing your spouse and putting your own pain aside in order to be present for your children.

Because the truth is, we’ve all suffered the consequences from the effects of war and wondered, “Is he really doing his best?”

How many times have I personally wanted to rage against my husband’s “best?” How many times have I flung cutting words at him for forgetting something, again? Many. Many times, I have raged against the “after” version of my husband, and many times I’ve sent words slicing through the air that were meant to cut deeply. As if the cut were all of a sudden going to change the make-up of his brain. As if the words could sting enough to snap him out of the forgetfulness.

For many years the residual effects of his mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) came across to us as being completely unthoughtful. If you loved us more, you would remember our family’s schedule. If you really cared about me, you wouldn’t always forget that I have a meeting every Wednesday at six. A thousand other things can substitute for those examples. And every time I thought of a new one, my husband’s “invisible” wound cut me deeply, further fracturing my relationship with him.

Because it looked like he just didn’t care enough to remember.

We’ve lived with the “after” version of my husband for almost seven years. In our family’s case, mTBI is only part of our story. Its effects may have been amplified by another “invisible” and signature wound of the post 9/11 wars, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which often goes hand-in-hand with TBI, according to military health studies. The comorbidity of the two compounds the very visible effects of both, in our house, which makes it difficult to say for certain which condition drives specific effects.

Fortunately, I have seen improvement. With the help of medical professionals and counselors, my husband’s forgetfulness has slowly gotten better. Either the wounds are healing, or he’s making new neural pathways to compensate for the shaken up old ones. While I am not a neurologist, these seem to indicate the realities of both neuroplasticity and post-traumatic growth – as painful as they may be.

Still, talking with my son helped me realize two things. Frank conversation about what we’ve lived through as a family related to my husband’s time at war is the best way for our family to heal. And perhaps, we should consider changing the way that we talk about the “signature” wounds of these wars.

After more than 100 service members suffered a traumatic brain injury in the wake of a January missile attack by Iran, it is important that we not minimize the complex effects of TBIs and their comorbidity with PTSD and other injuries. To do so is an injustice to the service members who suffer with them and the families who live with their very real effects. The more that doctors learn about brain function, the more apparent it becomes that brain trauma has a direct impact on the mental, emotional, and physical wellbeing of those affected.

Many people think this injury is “invisible,” but my children and I know it is anything but. Long after the war is over, hundreds of thousands of our men and women in uniform will continue to deal with the very real effects of these wartime injuries.