The war between Ukraine and Russia has become a topic of interest for American service members and veterans, but the consequences of the conflict may ripple through the U.S. military community in ways that are unexpected and that we are not prepared for. There may be a looming psychological health crisis for U.S. volunteers returning from Ukraine.

It is apparent that a large number of U.S. volunteers — most of whom are prior military or police — have joined Ukraine in the fight against Russia. Foreign military volunteers are not a new phenomenon, but the ability to become a foreign volunteer has been made easier by modern technology. With respect to the Russo-Ukrainian War, the Ukrainian government has set up a website to aid foreign volunteers in fighting alongside the Ukrainian military (fightforua.org). The website describes how to navigate the visa process, details where to travel upon arrival to Ukraine, and even includes a packing list. Shortly after the website launched, on March 6, the Ukrainian Foreign Minister said nearly 20,000 international volunteers from 52 countries had applied. It is unclear how many of those were Americans.

American casualties in Ukraine are mounting. At the time of writing this, there have been at least two confirmed American deaths. Additionally, two Americans have been captured and are being held as prisoners of war. They have been accused of war crimes and face the death penalty, and their fate is unclear. Military analysts have speculated that the war will continue to grind on and may even reach a stalemate. This means more American volunteers will likely be injured, captured, or killed.

The surviving volunteers who make it home uninjured may continue to face hardship upon their return. Reporters on the ground have been providing direct quotes from American fighters, and it has become clear that volunteers might face a unique type of psychological health crisis that was rarely seen after the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts.

The first reason for this is the ferocity of the war. This war is not like Iraq or Afghanistan. The fighting is more intense, and volunteers are seeing more combat than ever before while having fewer advantages that the U.S. military was able to provide previously (e.g., no air superiority). A fighter on the ground purportedly relayed the following to a grassroots reporter (anonymous quote published by @Battles.and.Beers, a former Marine, on Instagram):

“[I’m] former U.S. Military. Seen and been around some pretty decent combat before but not like this, man. Not even close. The Taliban was very amateurish in firefights and their IDF, if any, wasn’t very accurate. Don’t get me wrong, the fights were tough and we had some zinger days, but nothing like facing a uniformed enemy. There are jets and drones here bombing us constantly. Tanks, BTRs, BMPs, everything you can think of, they’ve brought it here… Here I get to be the guy sneaking around bushes and tree lines taking pot shots at troops and tanks. And here they get all the cool vehicles, air cover, and IDF. In a weird way, it’s given me a new respect for our old enemies.”

A 2021 study found that 4 times as many post-9/11 veterans have committed suicide than had died in combat. The report also found that veteran suicides were outpacing non-veteran suicides. The increased suicide rate was attributed to trauma, stress, and burnout. The high pace and brutality of combat in Ukraine may lead to more severe psychological health issues, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in returning volunteers. These issues might be exacerbated by other unique aspects of this conflict.

In this war, Americans are fighting against Europeans. In the Global War on Terror conflicts, Americans have benefited from experiencing an in-group/out-group phenomenon. In other words, they have been able to easily psychologically distinguish themselves from the enemy. That is beneficial to warfighters because it is easier to dehumanize an enemy if they do not look or act like you. When fighting in the Middle East or North Africa, it may have been possible to create a dissociation because the enemy “is not like us.”

This is not the case in Ukraine. This situation is exemplified in another purported quote from a U.S. volunteer on the ground: “It’s feeling like my days are numbered and I’d like to say some things. About me. Former military. Afghanistan veteran. Combat experienced. Three days ago I was in a trench line listening to artillery. I got to thinking about the perspective of the enemy. Just a few hundred yards away are the Russians. Living through the same bullshit I am… I’ve seen dead bodies before. Dead Taliban. Dead Afghan civilians. But that culture was so far removed and different from ours that I couldn’t really identify with it. I saw some dead Russians lined up by the road and I was shocked. I thought, ‘These guys could be me.’”

Moral injury occurs when an individual experiences or witnesses an event that contradicts their core moral values or beliefs. Moral injury, like PTSD, can leave lasting emotional scars. In a situation when warfighters are not able to dissociate psychologically from the enemy (e.g., Americans fighting Russians), the likelihood of experiencing moral injury may be higher.

Most veterans rely on the VA for medical and psychological services. Service-related PTSD can lead to a rating of 10-70% disability, depending on severity. If a veteran has PTSD so severe that it interferes with their ability to work, they may be eligible for a 100% disability rating. There is no VA rating for moral injury, as it is not currently a formal diagnosis. Because moral injury and PTSD have overlapping symptoms, some individuals may obtain a PTSD diagnosis as a result of moral injury.

Those who wish to receive a PTSD diagnosis from the VA are often asked to write a “stressor statement” that details events that they believe led to PTSD. Importantly, PTSD must be service-related – developed as a direct consequence of military service or developed while in the military. Volunteers who return from Ukraine may not be able to utilize VA benefits for psychological disorders (or physical injuries) developed or sustained while acting as a foreign volunteer because their stressor events are not related to their U.S. military service.

It seems unlikely that VA policies will shift to accommodate this new demographic of veterans. If this new psychological health crisis is acknowledged by military or political leaders, policy changes or support for these veterans may be slow or absent. As a consequence, a large swath of veterans may not be able to receive the psychological care that they need.

+++

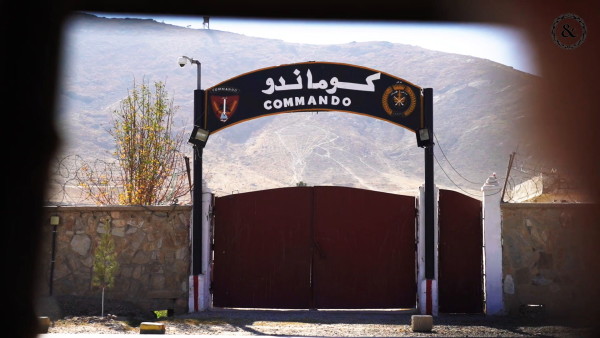

Dr. Janna Mantua is a research scientist at a DoD think-tank in the DC area. Dr. Mantua has spent 5+ years conducting performance enhancement research with SOF units and deployed to multiple sites in Afghanistan in support of SOF partner force selection.