“Painting a picture is like fighting a battle,” Winston Churchill once wrote, in what may be the dumbest statement ever attributed to the man who helped lead the Allies to victory in the Second World War and is otherwise rightly celebrated for his soaring rhetoric. “It is, if anything, more exciting. But the principle is the same.”

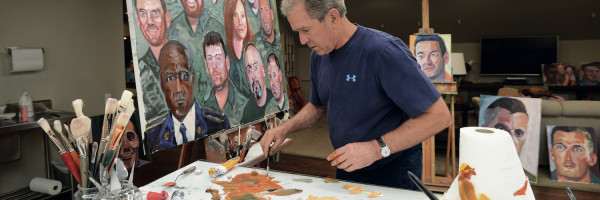

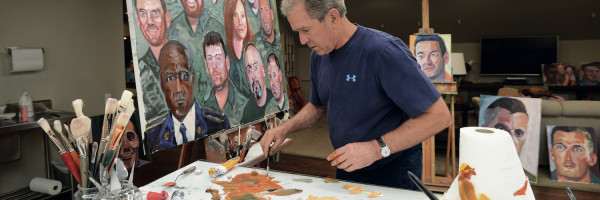

Actually, no, it isn’t. And there may be no better refutation of Churchill’s airy claim than the intriguing career path of president-turned-painter George W. Bush. The former chief executive spoke with Task & Purpose on Tuesday in his sunlit office in the George W. Bush Presidential Center in Dallas. Dressed in a brown suit jacket over an olive green Under Armour shirt, he was genial and warm, with a disarming sense of humor and a lightness of spirit suggesting retirement was definitely agreeing with him. The occasion was the unveiling of his new series of artworks. Entitled “Portraits of Courage,” the paintings depict 98 former members of the U.S. armed forces (there is one four-panel mural that includes 26 individual troops), most of whom fought in Iraq and Afghanistan during Bush’s time in office. They are men and women he got to know during the various wounded warrior events — including the W100K mountain bike ride and the Warrior Open golf competition — that he hosts each year as part of his extensive work on behalf of veterans.

Three paintings by George W. Bush. Left: Sgt. Daniel Casara; Middle: Sgt. Michael Joseph Leonard Politowicz; Right: Sgt. Leslie Zimmerman.

Bush cites Churchill, who mostly painted delicate landscapes, as the inspiration behind his post-presidential hobby. “I admired his leadership,” Bush told Task & Purpose, emphasizing the word in a manner that instantly brought back memories of his time in the White House. “I thought his paintings were very good, and I decided if he could, I could.”

But as the former president made clear as he paged through the hardcover volume of his new work, pausing here and there to critique a stray brush stroke, an oil painting can be reworked endlessly. “It’s paint and scrape, paint and scrape,” he told me, describing his process of revision and layering. “When this book came out, I started to look through it, of course, and I said, ‘Man, I wish I had that color a little better.’ Every one of these paintings could be improved upon.”

“Based on the paintings that he’s done,” suggested Robert Ferrara, an Army veteran, who was wounded by a roadside bomb in Iraq, “it has to be therapeutic for him.”

There are no erasures or do-overs when it comes to waging war. Bush often described his role as that of “decider,” and there were no more consequential decisions during his presidency than the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. The latter, which was based on false intelligence about Saddam Hussein’s weapons of mass destruction and nuclear ambitions, has been the subject of second-guessing since the first U.S. troops began massing in Kuwait in 2003. Among others, former National Security Advisor Mike Flynn and Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis have both criticized the decision. But nearly 14 years later, Bush said he doesn’t doubt for a moment that toppling Hussein was the appropriate course of action. “I thought it was the right decision then, and I think it was the right decision now,” he declared. Asked what he thought of Donald Trump’s assertion that it was a “big, fat mistake,” he shrugged. “A lot of people said that. I happen to disagree.”

Bush added that the 2007 surge in Iraq had demonstrated an important point: “Our military proved that we can defeat ISIS, though they weren’t called ISIS then.” I suggested that the battlefield had grown more complicated with the addition of Russia and Syria, among other players. “Is it?” he said. “I don’t know. The ingredients are the same. Thugs, the local people are sick of them. Bullies, who when rocked on their heels can’t stand up to Coalition forces. Syria has complicated it. But, just remember, in 2009, Iraq had free elections. Yeah, there was violence, but nothing like after we left. So my point is, it’s possible. And the sacrifice won’t be wasted.”

Soldiers, airmen, sailors, and Marines listen intently as then-President George W. Bush thanks the assembled service members who gathered at the Al Faw Palace for the opportunity to hear from their commander in chief, Dec. 14, 2008.Department of Defense photo

Bush has said that the hardest part of being in office was reading the casualty reports and seeing the brutal consequences of his policy first-hand: placing calls to sobbing widows, looking into the eyes of Gold Star families, visiting injured soldiers at Walter Reade and Bethesda as they practiced using a prosthetic limb or struggled with PTS. (Bush does not use the “D,” pointing out that such psychic wounds represent not a disorder but an injury that can be overcome.) “He told me the hardest decision he had to make was sending us into harm’s way,” said Michael Rodriguez, a retired Special Forces Green Beret, who now serves on Bush’s Military Service Initiative advisory board and whose portrait graces the book’s cover. “In the Special Forces community, we have a profound respect and love for the man. We never questioned anything under his leadership.”

Task & Purpose spoke to several of the veterans depicted in the portraits — all deeply devoted to the former commander-in-chief — who wondered whether his extraordinary painting project might be a form of art therapy: a way of exorcising his own post-traumatic stress or “moral injury,” a not-uncommon response to the experience of sending service members into combat.

“Based on the paintings that he’s done,” suggested Robert Ferrara, an Army veteran, who was wounded by a roadside bomb in Iraq, “it has to be therapeutic for him.” Michael Rodriguez, who recently designed a fixed-blade knife for the CKRT Forged by War program, said making art had changed his own life. “I was hospitalized in Bethesda, and they introduced me to art therapy,” he recalled. “I’m like, ‘I’m a damn war fighter. I don’t do fucking art.’” Eventually he tried it, though, “and I saw the beauty in art, the ability to say something when words just can’t do it.” Jay Fain, a Army veteran who was wounded by a roadside bomb in Iraq, agreed. “I know a lot of guys that use art as part of their therapy process, and I’m guessing that’s exactly why he does it.”

Painting of Sgt. 1st Class Michael R. Rodriguez.

“It’s an interesting question,” Bush said. “In a sense, it is therapeutic. Not that it unburdens my soul. It’s not the painting that unburdens my soul. It’s the belief in the cause and the people — to the extent that a soul needs to be unburdened. The painting was a joyful experience, and if that’s therapy, that’s therapy.”

“The painting was a joyful experience, and if that’s therapy, that’s therapy.”

It’s often said that every portrait is in some fundamental sense a self-portrait. If so, it’s impossible to look at these 98 extraordinary images without thinking deeply about the artist who made them: A leader who sent troops off to the battlefield, and who, so many years later, spends his days channeling the damaged but determined warriors who came home. In many cases, the eyes gazing out from these canvasses are plainly haunted by the horrors of war. Several bear expressions contorted with deep anguish. Spend a little time in the presence of these pictures, and one is overwhelmed by their subjects’ sacrifices, their courage, their strength and, in some cases, their turmoil. “So this one,” the president said, turning to page 115 and tapping the image of Staff Sgt. Alvis “Todd” Domerese with his forefinger. The portrait is one of the series’ most disconcerting and also most beautiful — Domerese’s large forehead a swirl of pink and grey, eyes narrowed, face twisted into a grimace. The picture is accompanied by a graphic depiction of war written by Domerese himself:

There was poverty like you can’t even fathom. I saw bloody and burned dead bodies in the streets. There was stagnant water with bugs and raw sewage here, there, and everywhere. Imagine the worst place you have ever been and multiply it by 100. Then add to it that we were being hunted like a buck in the woods.

“It’s very powerful,” Bush said of the letter. “And he filled out a questionnaire that mentioned he had night sweats. I’m thinking, ‘night sweats’… man. What’s going through the guy’s mind? So the painting turned out kind of harsh — not harsh, like condemning Todd. But reflecting the agony that was in his letter.” He’d seen Domerese a few days before and asked what he thought of the picture. “He said, ‘Man, it’s awesome,’” Bush recounted. “And of course that’s exactly what you’d expect him to tell the commander-in-chief. But I don’t want to in any way put out an image that would trouble somebody.”

Looking at the painting, I couldn’t shake the perception that Bush was also expressing something of his own state of mind. The pain was simply too palpable to be a matter of mere technique, reflecting a level of compassion and insight that can only be earned through genuine lived experience. Eventually, I put the question to him directly. After all, he himself regularly praises veterans for finding the courage to be open about their own internal struggles. Had he ever experienced symptoms of post-traumatic stress? “No. Not even close,” he replied flatly. “Not even close. Did I feel grief as the person responsible for them being there? Yeah, I felt it, because others were grieving. And when others grieved, I grieved with them.”

More often, Bush said, the troops and Gold Star families he met expressed pride in their service. “I can’t tell you the number of times at Walter Reed or Bethesda a troop would look at me and say, ‘I’d do it again,’” he recalled, noting that two of the men in the book had returned to combat with prosthetic limbs. “I’m sure there are people that are bitter and angry. I can understand that. I would occasionally run into one person, I’d try to be empathetic. But it’s hard for people to understand how uplifting it is to be around such people of character.”

Our first glimpse of George W. Bush, the artist, came in 2013, courtesy of an unemployed Romanian taxi driver. “My little sister was hacked by Guccifer,” he recalled, referencing Dorothy Bush Koch, whose AOL account was compromised in one of a series of stunning if easily executed hacks. Bush had just started painting, and he’d emailed his sister a few images. “The one that got the most notoriety was my feet in a bathtub,” he went on with a light chuckle. “I did the painting for several reasons. One, I was trying to learn perspective away from you. Secondly, I like the idea of painting water hitting water. And thirdly, it fit to my sense of humor. So yeah, that one got leaked out there, but you know, that’s okay. I understand people are interested. Most of my painting is very private, and that’s the way I like it. But I obviously made the decision to put these out for public consumption, because I wanted people to pay attention to our vets and what they’re dealing with.”

Painting of Lt. Col. Kent Graham Solheim.

The bathtub picture, and another that depicted the former president in the shower from behind, his face reflected in a small circular mirror, were widely ridiculed in the media. But Bush kept at it, working with a series of teachers, and studying the work of masters like Lucien Freud, Jamie Wyeth, and Fairfield Porter. He spends endless hours every day in his studio now, mixing various hues from a handful of primary colors, listening to George Jones and Van Morrison, or sometimes the occasional Texas Rangers game, on his Sonos speakers. In 2014, he mounted his first solo exhibition, “The Art of Leadership,” made up of 30 portraits of world leaders with whom he’d worked during his two terms in Washington, drawing some friendly praise from art critics. Especially noteworthy was the sharp depiction of Vladimir Putin: hollow-eyed, tight-lipped and corpse-like. Though clearly the effort of a novice, it’s a powerful piece, lent a mysterious resonance by the complicated public relationship of artist and subject.

As impressive as that series was, Bush’s latest works are in a new category altogether. Just five years after first picking up a brush, the ex-president has turned himself into a legitimate artist. His paintings are no longer historical curiosities or fodder for late-night comedy. They’re extraordinary works of art in their own right, demonstrating a confidently loose style, a fluid sense of color, and an ability to capture not only a subject’s likeness but his or her inner emotional state. Speaking of his world leaders series, Bush noted, “If you look at the brush strokes, they are very limited, as if I was trying not to make a mistake. So I think the looseness is an indication of growth.”

“Throughout my presidency, I met many wounded vets, and met with families of the deceased — the vast vast majority of whom, I tried to lift their spirits and they lifted mine.”

As much as anything, the paintings are an expression of the profound respect and tenderness Bush clearly feels for the men and women who served under him. “We all shared something,” he said. “And that was war. I vowed as president that I would make deliberate decisions, because I really knew the consequences. And that if these men and women were in combat, I’d support them all the way. And I did. Throughout my presidency, I met many wounded vets, and met with families of the deceased — the vast vast majority of whom, I tried to lift their spirits and they lifted mine.

“I believe our country’s future is in good hands if we help them,” he went on. “They’re remarkable individuals. I’m a Vietnam-era product. People are worried about divisiveness and all that stuff now. We were really divided then. There was a draft and people didn’t understand what was going on. And there was 55,000 casualties. And it was a horrendous time. Big protests. Big race riots. And our vets were treated despicably. Friends that came back from Vietnam War were spit on. And that affected me.”

I brought up one of the subjects of his portraits: Juan Carlos Hernandez, an Army veteran who lost his right leg in Afghanistan when an RPG hit the Chinook helicopter he was flying in. Born in Mexico, Hernandez crossed the border illegally when he was nine and joined the Army just out of high school, out of a desire, as he puts it in an accompanying profile, “to give back to the country that had done so much for me and my family.” During his presidency, Bush made a big push for comprehensive immigration reform, designed to strengthen border security while also providing a path to citizenship for the undocumented immigrants already here. The effort was unsuccessful, but Bush insisted, “The plan I proposed could easily come back to be. Look the politics are tough. Hernandez is good example for Americans, when they think about their position on this very hot-button issue. To remember this man was willing to wear the uniform of our country. Hernandez became a citizen at Bagram Air Base. And I had the privilege of watching others who serve our country get sworn in as citizens after they were wounded. So as we debate the issue, let’s think about the contributions that many are making.”

U.S. military veteran Robert Ferrara talks in front of a mural painted by Former President George W Bush during a press preview of an exhibition of Bush’s paintings of veterans in Dallas, Tuesday, Feb. 28, 2017.AP Photo by LM Otero

Though his own service during the Vietnam war — he was a member of the Texas Air National Guard — became a contentious issue during the 2004 campaign, current and former service members I spoke with venerate Bush as a leader of rare conviction, who has dedicated his post-presidency to their welfare. Whether or not one agrees with his foreign policy decisions, few doubt that they sprung from a deeply held belief in the goodness of the American people and the ennobling power of the democratic system. “I think it has a lot to do with my religious beliefs,” he said. “I believe a gift from an Almighty, deep in everybody’s soul, is the desire to be free — free to choose, free to worship the way you want to worship. And if given that choice, people will go to extraordinary lengths to realize that freedom. And I used to say it’s not an American gift to the world, it’s a universal thought.”

He noted that free societies contribute to international peace. “What’s easy to overlook is the contribution of Japan and Korea to peace in the Far East,” he said. “One was at war with us, and the other was in total turmoil, and yet those democracies evolved. It takes time to evolve. And as they did, they became allies in helping to keep the peace.”

“Our military proved that we can defeat ISIS, though they weren’t called ISIS then.”

I asked him what he thought about the isolationist sentiment that had become a key element of the 2016 Presidential race. “I warned about isolationism in the State of the Union address,” he said. “We were isolated prior to World War II. I admire Winston Churchill for his leadership, when their strongest ally went tepid in the face of a totalitarian ideology. And hopefully people learn the lessons. There’s a lot of voices out there talking about the need to never forget values that have mattered over the course of time.” He mentioned Africa, where the effort to combat HIV/AIDS was a cornerstone of his presidency. “America’s a compassionate country,” he said. “I used to say all the time, ‘We don’t conquer, we liberate.’ Because of the generosity of the American people, millions are alive on the African continent today that wouldn’t have been.” The Bush Center is now working on an initiative to combat cervical and breast cancers in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. “My case is, it’s in our interest to do so,” he said. “We can’t solve every problem, but we can work on the big ones.”

It’s important work, and a large painting of some of the women whom the program has helped hangs in a corridor just outside Bush’s office. But it’s clear that the contribution that’s closest to his heart is his work on behalf of the men and women who serve in the armed forces. “I’ve got a platform,” the man known as 43 noted with a self-deprecating wink. “It’s not quite as big as the last one. But I intend to use it to help vets, and this book is just another way of doing so.”

Portraits of Courage is on view through Oct. 1, 2017, at the George W. Bush Presidential Center. The book can be purchased via the center’s website.