If Hezbollah agents abducted a CIA station chief today, tortured and held that person in captivity, and eventually neglected her or him so egregiously that she or he perished, it would trigger an international crisis.

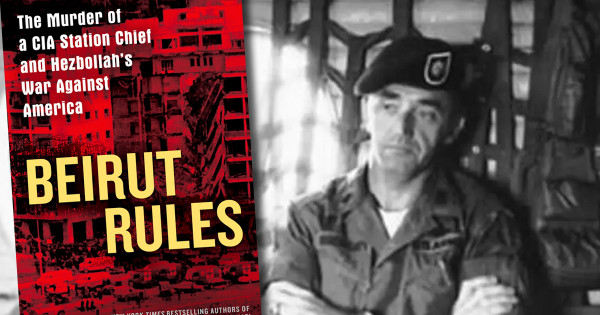

This is precisely what happened in Lebanon in 1984, when militants snatched William Francis Buckley from his car in Beirut.

Yet, an international crisis did not ensue. The kidnapping caught the CIA—and the Reagan Administration—off-guard. Losing their top clandestine official in the country threw the entire U.S. bureaucracy—both in Washington and in Lebanon—into disarray. In 1985, after more than a year of fumbling, proof that Buckley died in captivity came to light.

It would be more than 20 years before the United States exacted partial revenge.

Buckley, a veteran CIA officer with an impressive service record, deserved better than to die as a hostage, and his story deserves more attention. Fred Burton and Samuel M. Katz set out to correct this latter injustice in Beirut Rules, chronicling the saga of Buckley’s abduction as well as the bureaucratic bumbling that sealed his avoidable fate.

Burton, a former Diplomatic Security special agent who worked on the Buckley case in the 1980s, and Katz, an expert on terrorism and Middle East issues trained by the IDF, secured interviews with Buckley’s surviving family; as a result, they offer perhaps the most complete portrait of Buckley’s early life available to date. It is a sensitive depiction, by two admiring writers, of an honorable man killed in the line of duty.

The reason Buckley’s story gets overshadowed is because of its context.

Lebanon in 1984 was a difficult place to be: the long litany of abductions, bombings, ceasefires, and massacres that make up the story of Lebanon’s civil war reached their apogee in 1983, and global attention had largely moved on from that benighted country by the time masked gunmen bundled Buckley away. It is in providing this context that Burton and Katz’s book falls victim to shallow analysis and sophomoric writing.

There are two kinds of books: books that try to change your mind, and books that tell you that you are already right. Beirut Rules falls in the latter category. For Burton and Katz, almost all Hezbollah recruits are “bloodthirsty,” filled with animalistic rage, “ruthless,” and, most damning, “ambitious.”

“Horrible conditions mattered little to the Iranians,” the authors remark, underlining the bestiality of Iranian political agents in Lebanon.

Although the book refers frequently to the “Shiite slums” in south Beirut, the authors never offer an explanation for their existence (the rapid globalization of the Lebanese economy in the 1950s and 1960s exacerbated income inequality, and particularly affected Lebanon’s historically disadvantaged Shiite population). Palestinians, Lebanese Shiites, Iranians, and Arabs appear interchangeable in the narrative, despite representing distinct political groups (and not, as the authors state, “ethnicities”).

Even the “good guys” get inconsistent treatment. Bob Ames, the CIA’s most capable officer in Lebanon, died in the April 1983 US Embassy bombing. Burton and Katz cannot decide whether Ames’ presence at the embassy was a “pure coincidence” or whether “there are no accidents in terrorism.”

The problem with this kind of imprecision is not simply that it is bad writing. It obscures the pertinent questions about the entire Buckley affair and points the reader’s attention elsewhere.

Buckley died, Burton and Katz imply, because that’s what happened to Americans in Lebanon in the 1980s. The book never explains why Hezbollah kidnapped Americans in that period, why Buckley was in particular danger, or even why war happened in Lebanon in the first place. The book only mentions the Iran-Contra affair in passing, despite the fact that the arms-for-hostages deal began during Buckley’s captivity and very likely prolonged Hezbollah’s hostage-taking program in Lebanon.

Discerning readers should ask themselves what Burton and Katz are not explaining to see the outlines of the book’s ideological agenda.

“Diplomacy in a place like Lebanon mattered only when it was backed by massive force,” they claim. Yet they do not explain why that should be the case, nor do they consider how massive force itself might undermine diplomacy. They note that despite Buckley’s long career, he went to Beirut without clandestine experience—yet do not delve into how Buckley’s lack of clandestine experience exposed him to undue risk. Practices that came naturally to clandestine officers—varying routines, keeping fewer written notes—might have saved Buckley’s life, or at least minimized the damage from his kidnapping.

Buckley himself understood these vulnerabilities: he accepted the position only reluctantly from CIA Director Bill Casey. Burton and Katz characterize his acceptance as noble self-sacrifice, but don’t ask why the CIA leadership either ignored or accepted the shortcomings in Buckley’s expertise.

“Everything in Beirut,” the authors state, “encompassed violence and hatred.”

Yet moments after Hezbollah gunmen snatched Buckley from a Beirut street in broad daylight, a neighbor who witnessed the kidnapping from his balcony reported it to the US Embassy. In Beirut, neighborhoods are tightly knit—particularly during the war years, community ties could mean the difference between life and death. There are few secrets in that city, then as now.

Buckley’s neighbor likely knew he was a CIA officer, and knew Buckley was in danger. Burton and Katz ignore the neighbor and focus on the gunmen, forgetting that one was as Lebanese as the other. Surely in his time in Beirut, Bill Buckley knew more than violence and hatred. Burton and Katz rightly argue that Buckley deserved better. Unfortunately, he still does.

Emily Whalen is a doctoral candidate in History at the University of Texas – Austin. Her dissertation title is The Lebanese Wars: Civil Conflict and International Intervention, 1975-1985.She is currently a Smith Richardson Predoctoral Fellow in International Security Studies at Yale University. Her website is www.emilyingridwhalen.com.