This article was published in collaboration with the editorial team at Longreads. It was originally published on April 9, 2018.

The thing that everyone remembered about the man in the light gray sweatshirt was how composed he was, how polite and respectful. One morning this past summer, he quietly entered a Wells Fargo bank branch in the Atlanta suburbs in a desperate state. But he didn’t curse or even raise his voice. He just calmly relayed the litany of setbacks and obstacles that had led him to an extraordinarily reckless act.

Brian Easley, a 33-year-old, standing 6 feet 2 inches, with close-cropped hair and glasses, had woken up on the morning of July 7, 2017, in Room 252 of a $25-a-night hotel nearby, where he’d been living, scraping by on a small monthly disability check from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

A former lance corporal in the Marine Corps, he had served in Kuwait and Iraq as a supply clerk, separating with an honorable discharge in 2005. But his transition to civilian life had been fraught. Joining his mother in Jefferson, Georgia, he found himself suffering from back aches and mental illness. He met a cashier at the local Walmart, and soon they married and had a daughter together, but he disappeared for long stretches as his symptoms worsened. After his mother died in 2011, he bounced around — alternating between relatives’ spare rooms, VA mental hospitals, and nonprofit housing facilities. During a few especially difficult periods, he slept in his car.

By the summer of 2017, Easley had lost even that option. His usual disability check from the VA had mysteriously failed to materialize, and rent was due. If he couldn’t cover it, he’d be on the street, and the thought terrified him. In the first week of July, Easley called the Veterans Crisis Line repeatedly to inquire about the status of his disability payment. When they hung up on him, he called back. On Monday, July 3, Easley made his way to the VA’s Regional Benefits Office in Atlanta. But after an argument with staffers there, he left in humiliation, his issue unresolved.

A few days later at around 9:30 a.m, the Marine veteran entered the Wells Fargo branch, a faux colonial building on Windy Hill Road, a six-lane commercial thoroughfare, and claimed that the backpack slung over his shoulder contained C-4 explosive. He allowed several employees and customers to exit and informed the two remaining workers that they should lock the doors and stay put. Then he began making calls, dialing 911 to let the authorities know what was happening, and a local news station, WSB-TV, to explain his predicament. “They took everything,” he told the assignment editor who picked up the phone. “With my last little bit of money I got I’ve been able to hold up at a hotel, but I’m going to be out on the street and I’m going to have nothing. I’m not going to have any money for food or anything. I’m just going to be homeless, and I’m going to starve.”

Easley spent nearly 38 minutes on the phone with the editor, relating his military history, his love for his young daughter, and his frustrations with the VA. At one point, he allowed her to speak with the hostages. One described her captor as “very respectful.”

Easley insisted he didn’t want to harm anyone. “I already told them if I detonate this bomb, I’ll let them go first,” he promised. “These ladies are very nice, and they’ve been very helpful and supportive.” He said he had no intention of robbing the bank, and though an employee had fled leaving piles of cash just sitting out at their workstation, he showed no interest in it. His focus was exclusively on his own money — that monthly disability payment from the VA.

“How much money are we talking about?” the editor asked.

“Not much,” Easley said. She pushed for a dollar figure.

“Eight hundred and ninety-two dollars,” he answered.

As Cobb County police deployed around the Wells Fargo, establishing an incident command center in the parking lot of the nearby Texaco gas station, two snipers, Officers Dennis Ponte and Brint Abernathy, took up positions at the edge of the bank’s rear parking lot. Chief Mike Register, who’d only recently taken over the department, arrived on the scene shortly thereafter. Easley, meanwhile, spent most of the morning on the phone.

In addition to WSB, he spoke to his wife, Jessica, and her cousin, Yolanda Usher. He fielded calls from random bank customers, politely informing them that there was an emergency underway and that they should call back later. He told his daughter, Jayla, then 8, that he loved her and to work hard in school. “Okay, Daddy,” she said. “I love you.” Through it all, he kept his cool, even indulging in some dark humor. He mused that he might be the “worst bank robber ever.” And when the WSB editor asked him for his Social Security number, he joked, “You’re not going to steal my money too, are you?”

As the three-hour ordeal unfolded, he remained unfailingly polite to his captives, allowing them to place calls to their loved ones and even maintain contact with police. “He just kept saying, ‘Ladies, I’m so sorry,’” one of the hostages told the Georgia Bureau of Investigation later. “And I was like, ‘I feel really bad. I understand. You’re in a hard spot.’ And he said, ‘Thank you. I appreciate that.’”

As reasonable and mild-mannered as he seemed, Easley did show some clear signs of mental illness. In his call with WSB, he explained that he was being followed and had been the victim of four kidnapping attempts, which he attributed to his half-brother Calvin and a secret society. “I don’t know these people,” he said. “They seem to be able to track me wherever I go. They have my information.” During several difficult moments, he held his head in his hands and sobbed, muttering softly, “I just snapped.”

In an effort to understand the many factors that led to the Windy Hill Road incident, I spent seven months speaking to Easley’s family members and fellow Marines, officers of the Cobb County Police Department, Veterans Affairs officials, community activists, and experts in law enforcement, mental health, and military transition.

I found a story that was considerably more complex than it first appeared, involving the failure of the nation’s safety net; VA policies better designed to exploit former warriors than to assist them; a confused police response; and maybe an undercurrent of racial bias, one that the community liked to think it had outgrown long ago.

It was also the story of four former members of the U.S. armed forces, whose paths converged one morning in July on a busy suburban thoroughfare. Before the day was over, two would be recounting the incident to investigators, another would be facing the news media, trying to explain to the public just how it happened, and a fourth would lay dead on the floor of the bank, his head pierced by a single gunshot.

* * *

Born in 1983, Brian Easley was a mama’s boy as a child, his thumb rarely straying from his mouth. The youngest of eight kids, Easley lived with his siblings and parents, Barbara Easley and Bobby Lee Brown, in a ranch home in Williamstown, New Jersey. It was a tight fit — 10 of them in all, crammed into three bedrooms — but they made it work. Located south of Philly, it was a safe, quiet neighborhood with a small-town feel, notable mostly for the aroma of pizza sauce from the local cannery, which wafted across the local sports fields every afternoon. Barbara was an indomitable woman, laboring tirelessly to make sure none of her children ever felt neglected despite their parents’ modest income. Brian was the baby, her very last, and she doted on him.

Easley had few friends growing up, but he was close with his brother James, the next oldest, joining him in PlayStation marathons that typically went on until there was no more game to play. Despite his height, he was soft-spoken and timid as a teenager. In school, he was painfully shy around girls, later confiding to his fellow Marines that he’d been a virgin when he signed up at 18.

Twelve weeks of basic training at Parris Island outwardly transformed him, precisely as the military intended. Watching him graduate in a ceremony at Camp Lejeune, his family members were dumbstruck. “I could not believe my eyes, how polished he was, how sharp, tall, strong,” said his brother Calvin, the oldest sibling. “I sat there in awe the whole entire time. He went in a little boy, and they turned him into a man.”

Assigned to the 2nd Marine Logistics Group, based at Camp Lejeune, the soft-spoken recruit fell into a circle of friends who each quickly took him under their wing. To them, Easley seemed less a warrior than a big goofy kid, more content to eat cereal and watch his favorite anime series than to hit the local bars or shoulder a rifle.

The group formed a tight bond, fortified during their deployment to Kuwait in 2003. Though Easley’s fellow Marines would roll their eyes at his devotion to Tolkien novels and compare him to Steve Urkel, the teasing was affectionate. His tranquil demeanor, generosity, and maddening compulsion to apologize for the smallest offense — and then apologize for doing so — earned him the nickname Easy. He mostly stayed out of the boisterous debates that often preoccupied his unit, only to pipe up seemingly out of nowhere with some deliberately inane assertion, like, “I hear Somalia has the world’s strongest navy,” and then hold a poker face as long as he could — which usually wasn’t long.

Deployed to Iraq in 2005, Easley was stationed at the Al-Taqaddum Air Base, known as TQ, where he served as a warehouse clerk with the 2nd Supply Battalion. Easley’s job was to fill requisition orders for Marine combat units operating throughout Al-Anbar province, where insurgents, including the nascent al-Qaeda in Iraq, were mounting a surprisingly fierce campaign to drive American forces from the Western Euphrates River Valley.

The work was arduous — up to 17 hours a day for months at a time without a break — contributing to the chronic back pain that would plague Easley when he eventually returned to civilian life. “The warehouse jobs are out in the rear, so I wasn’t on the front lines,” Easley told WSB. “I had one close call during a security detail, but that’s about it.” Nevertheless, according to James Dunlap, who served with him, mortar fire was a regular feature, often sending everyone scrambling for bunkers. “I’m thinking, ‘We’re in supply, we’re not going to see this type of action,’” he recalled. “But when they say ‘Every Marine is a rifleman,’ they mean it.”

Following his honorable discharge in 2005, Easley returned to his mother’s home in Jefferson. He met a woman, Jessica Tate, and they moved in together and eventually got married. Around Jessica, Brian seemed fine — strangely quiet maybe, but also devoted, sweet, and easygoing. To his family, though, it was clear that something was wrong. “We noticed a difference in him right away,” Calvin recalled. Diagnosed with PTSD, and suffering from schizophrenia and paranoia, Easley told relatives he was barred from reenlisting. He often set off on long walks by himself. On one occasion shortly after his discharge, he grew so upset at a sibling’s teasing that he flew into a rage that left the family shaken.

These symptoms are not uncommon. “After we got out, it got rough for everybody on the tour,” James Dunlap explained. “It’s easier to be in a war zone than live life out here. You’re not in the Marine Corps anymore, so what’s your purpose?”

* * *

In 2008, Jessica became pregnant. Both of Brian’s parents fell ill around the same time, and he found himself in New Jersey hoping to help care for them, visiting Georgia only briefly for the birth of his daughter, Jayla, but vowing to come back soon.

“He never did come,” Jessica recalled. His phone rang and rang. Eventually, family members told her how he’d just stood up one day, announced he was going for a walk and never returned. “I was like, ‘Oh my god, I just had his baby and he disappeared. Is he leading a double life?’” she said. Fearing for his safety, she spent many nights crying herself to sleep. “I’m tearing up now just thinking about it.”

It turned out Easley had checked himself into a VA mental hospital. Upon his release, he stayed with a brother in New Jersey. Aside from one trip to Georgia to meet Jayla when she was about 3, he mostly kept his distance. He explained to Jessica that people were after him — he wouldn’t say who — and he didn’t want to put his family in danger.

Just a week or so before Barbara Easley died, in 2011, Brian once again “up and walked off,” Calvin said. Voicemails and texts went unreturned. The funeral came and went with no sign of Brian, and years went by without a word. After calling every VA hospital in the directory, Jessica tried to move on.

When he surfaced again around 2014, Easley moved in with Calvin in Georgia, taking his medication, keeping his VA appointments, and generally trying to get his life back on track. He said he’d been in Orlando, taking filmmaking classes. He made no mention to his brother about a brief spiritual detour, as a follower of the Black Israelites, a religious sect famous for preaching that African Americans are the true Jews. But perhaps it isn’t surprising that in his troubled state, Easley had gravitated toward a tight-knit community. “I think he wanted to belong to something larger than himself,” recalled Dunlap, who was in touch with Brian during this period. Eventually Easley “woke up,” Dunlap said, and was ejected from the group.

Easley didn’t spend much time in Georgia with Calvin and his wife, Anita—maybe a half year or so—before he was on the road again, moving to New Jersey to live with another brother. After several episodes, though, he returned to Marietta in early 2017, enrolling in computer classes at Lincoln College of Technology, a for-profit college located in a strip mall. He had bought Jayla a phone and called regularly, helping her with homework and joining her in a prayer via Facetime nearly every night. Some of his money from the government went toward child support, and he wired more whenever Jayla needed it. Not long before Brian walked into the Wells Fargo, he had the idea to surprise Jayla with a dog. Jessica thinks the realization that he wouldn’t be able to follow through may be what set off the episode.

* * *

In the spring of 1971, 10-year-old Mike Register was walking through an affluent neighborhood of Macon, Georgia, when a pair of young men in a car waved him over with a proposition: How would he like to earn $5 helping out with some yard work? It was a tempting offer, but the situation seemed off. For one thing, Register was white, and the men in the car were black. Job offers like that just didn’t happen in Macon in those days. Register bolted toward the woods, but the men gave chase, abducted him, and later kept him captive in an abandoned house, demanding a $5,000 ransom from his family. His mother alerted the authorities and delivered the money as instructed.

All told, Register spent 20 hours as a prisoner, while the men debated whether to kill him. Eventually, they essentially let him go, threatening to slaughter his family if he said a word. The boy didn’t heed the warning. At some point, he’d managed to snag an ID belonging to the ringleader, 20-year-old John Plummer. After his release, Register presented the card to local police, resulting in Plummer’s arrest and eventual conviction. (The other two men were never identified.) At the trial, which drew charges of racial bias from the defense team, the all-white jury found Plummer guilty of kidnapping, then deliberated for just 10 minutes before suggesting a life sentence.

Surprisingly unguarded for a chief of police, now leading a department of more than 600 officers, Register is a voluble storyteller, recounting this traumatic chapter from a difficult childhood in an easygoing, buttery drawl without a hint of disquiet. Asked how the terrifying crime he experienced as a child may have affected his response to the Wells Fargo hostage-taking, he insisted it had no impact. “I certainly have empathy for anyone who is held against their will,” he said. “Certainly that’s a part of my life, and I’m very thankful that it turned out the way it did for me. But no matter what my life experience may have been, I certainly try to be objective with any situation.”

Register enlisted in the reserves in his early twenties, joining the 11th Special Forces Group and becoming what was then known as “SF baby,” jumping right into commando training without any prior military experience. He thrived in the reserves, taking time off from his work as a police officer with the Cobb County PD for intensive training and deployments to Germany, Haiti, and Belize, among other countries.

By 2002, when Brian Easley entered the Marine Corps, 40-year-old Register was in Afghanistan with the 20th Special Forces Group, serving on a mobile reconnaissance team. After retiring from active duty in 2005, the same year Easley left the service, Register worked for the Department of Defense, devising strategies to counter the insurgency’s devastating use of IEDs. In 2014, he returned to suburban Atlanta and eventually resumed his career in law enforcement, becoming chief of police for Clayton County, 20 miles south of Atlanta.

Register was recruited as chief of police for nearby Cobb, which includes the city of Marietta, just three weeks before Brian Easley walked into the Wells Fargo. Though both counties belong to the metropolitan Atlanta area, they pose distinct challenges for law enforcement. Whereas Clayton is economically depressed and predominantly black, Cobb County is a mostly white, affluent bedroom community that was represented in Congress by a former leader of the nativist John Birch Society for nearly a decade and was long known for its “legendary intolerance,” as The Atlanta Journal-Constitution put it.

Though an influx of recent transplants, mostly young professionals, has tilted Cobb’s politics left, the county retains its reputation as a stronghold of white conservatism. Despite the 2017 opening of a new stadium for the Atlanta Braves, Cobb had for years steadfastly refused to allow the construction of a rail link to Atlanta’s transit system, in part out of a longstanding desire to wall itself off from the so-called “black Mecca” across the Chattahoochee River. (Years ago, a county commissioner infamously declared he’d stock the river with piranha to block rapid transit.)

Although the violent crime rate is considerably higher in Clayton than in Cobb — with nearly eight times as many murders on a per capita basis in 2016 — Register’s new position is in some respects trickier to navigate, given Cobb’s fast-changing demographics and more fraught political atmosphere. As chief of police for Clayton County, Register was an advocate of transparency and community policing initiatives, and Cobb community activists viewed him as an ideal choice to take the helm of their department as it sought to transform itself from a hidebound reminder of the region’s troubled past into an exemplar of the bighearted cosmopolitan New South.

To judge by the stream of racially charged incidents that have made the news in the area in recent years, change was long overdue. In 2015, the county’s only black commissioner reported what appeared to be racial profiling by an undercover officer — a complaint that elicited a shrug from her fellow commissioners. A few months later, the same officer was involved in a disturbing encounter with a black driver that was captured on dashcam. (“Go to Fulton County,” he said. “I don’t care about your people”). Following a suspension, the officer resigned.

The community’s negative perception of the department was confirmed last year in an independent report on police operations drawn up at the county’s behest by the International Association of Chiefs of Police. Although the report did not find evidence of systematic bias, it identified “a concerning deficit of public trust in and among a portion of the population.” It also made 34 recommendations, many of which the Register is now implementing. Among a host of other changes, he ordered that all members of his department receive additional training in crisis intervention, crime prevention, cultural diversity, and fairness in policing. The chief has also considered a proposal by the Cobb Coalition for Public Safety to ensure that mental health professionals are called upon in crisis situations. Some departments mandate that specially trained teams be deployed whenever an incident involves a potential mental health emergency, but in Cobb County, such experts are only brought in at the request of the crisis negotiation team. In Easley’s case, no such request was ever made.

* * *

According to the Marshall Project, law enforcement is the third most common occupation for military veterans, after truck driving and management. In part, this is attributable to the preferential hiring encouraged by initiatives like the 2012 federal program Vets to Cops. A career in law enforcement has an additional appeal to veterans, offering, as few occupations do, the sense of fellowship, duty, and shared risk that they experienced in the military. “I think that everyone, no matter who you are, you want to belong to something,” Register said. “People that have served in the military understand that they are part of something that is great, admirable, honorable, and that is important.” A police force, he added, “is a natural transition” — conferring membership in what Ken Vance, executive director of the Peace Officer Standards and Training Council of Georgia, termed a “blue brotherhood.”

A substantial percentage of CCPD officers are veterans — several of whom, like Chief Register, played key roles in the Wells Fargo incident. Sgt. Andre Bates, the lead negotiator, served in the Marine Corps, as did Officer Dennis Ponte, the sniper who took Easley’s life.

In his 2016 book, Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging, Sebastian Junger advances a powerful case linking veterans’ struggles with PTSD largely to the difficulty of navigating the fraught transition from the tight-knit world of the armed forces to the more isolating and superficial existence of life on the homefront.

This certainly tracks with Brian Easley’s experience. Joining the Marine Corps at 18, the former wallflower quickly found the camaraderie, friendship, and shared sense of purpose that had largely eluded him until that point. After his discharge, cut off from his social group, he found himself increasingly alienated and adrift — an experience that undoubtedly contributed to his mental illness. Soon, aside from his immediate family and Jessica, he was more or less on his own, so lonesome in those early years that in addition to his primary job at a Home Depot distribution center, he took a second gig at a Church’s Chicken not for the money, he told Jessica, but “just to pass the time while you’re at work.”

When I asked Register how he has dealt with his own traumatic experiences — the kidnapping as well as his later service in Afghanistan — he shrugged off the question, more comfortable speaking about the prevalence of PTSD in general. But as frightening as his childhood ordeal clearly was, his success in dealing with it is not surprising: After helping to foil his own abduction, he was hailed as a hero by the national news media. In recognition of his bravery and quick-wittedness, the local police department named the 11-year-old its honorary chief of detectives.

“Humans don’t mind hardship, in fact, they thrive on it; what they mind is not feeling necessary,” Junger wrote in Tribe. “Modern society has perfected the art of making people not feel necessary.” Register seems to have found his purpose and his community in law enforcement, as did Bates, Ponte, and the many other veteran members of the CCPD.

* * *

As Brian Easley told the editor at WSB, the two hostages, and the crisis negotiator — basically anyone who would listen — his monthly disability check from the Department of Veterans Affairs came to $892. The VA confirmed that his last payment, for that precise amount, was sent on June 1. So perhaps it’s no wonder that when July 1 came and went, and the expected funds were not in the account, Easley began to panic.

According to WSB investigative reporter Aaron Diamant, Easley called the VA’s Veterans Crisis Line eight or nine times that week, including twice on the morning of the incident, and he was “hung up on a few times.” (A VA spokesperson declined to comment on Diamant’s reporting.) According to its mission statement, the VCL was established in 2007 to “provide 24/7, world-class suicide prevention and crisis intervention services to veterans, service members, and their family members.” But as the demand for its services has surged, the program has been plagued with issues. A March 2017 report by the VA’s Office of Inspector General found a number of shortcomings with the VCL, including deficiencies in operations and quality assurance. In response, the VA issued a press release touting improvements; a few months after Brian Easley’s death, it announced plans to open a third call center to handle another spike in demand.

According to Lincoln Educational Services senior VP for student financial services Rajat Shah, Easley visited the school’s Marietta campus on June 30 to discuss the possibility that his money had been garnished due to a tuition issue. A counselor at the school called the VA directly, and Easley was given an appointment at the VA’s Regional Benefits Office on July 3. He “was extremely agitated and belligerent,” a VA spokesperson told me, and as a result, was briefly placed in handcuffs. “Once Easley calmed down,” the spokesperson said, “police removed the handcuffs and a VA benefits supervisor … explained to him that his compensation check was recouped due to a debt he had created by his failure to complete college courses.” Easley agreed to return on July 6 with the proper documentation to set up a payment plan “and left the regional office voluntarily.” He never returned.

Perhaps unwittingly, Easley had become caught in a financial squeeze involving what are known as overpayments — a common pitfall for recipients of Post 9-11 GI Bill tuition assistance. Government tuition payments are made in full directly to an academic institution, but if a veteran drops too many courses or fails to attend class, the VA will initiate a process to recover the money directly from the student. According to Shah, Easley last attended class in late November 2016. He would have had to miss just six days of his module to trigger a mandatory notice to the VA, though Shah said the school tries to contact a student before taking that step. Easley’s overpayment was $1,163, so after the $892 was deducted from his account, he owed a mere $271.

If in fact, Easley did miss some classes, it would hardly be a surprise. He was suffering from a severe mental illness, something the Department of Veterans Affairs, which was responsible for his care, certainly knew. Although the VA claims it sent Easley five letters informing him of the overpayment, his erratic housing situation meant he probably never received them.

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest military news and culture in your inbox daily.

According to Carrie Wofford, president of Veterans Education Success, a nonprofit watchdog and advocacy group, the issue of veterans like Brian Easley failing to understand their liability for GI Bill overpayments “happens literally all the time.” A 2015 report by the General Accounting Office estimated that a quarter of all veterans receiving tuition assistance are billed for overpayments, many without ever fully understanding how the system works. “Because VA is not effectively communicating its program policies to veterans,” the report said, “some veterans may be incurring debts that they could have otherwise avoided.”

Although Shah said Lincoln staffers tried to help Easley with the VA, the school has drawn criticism in the past for an apparent indifference to the welfare of its students. “The programs are costly, more than twice as much as at local community colleges,” the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee the committee wrote in a 2012 report, “and Lincoln makes virtually no investment in student services despite enrolling the students most in need of these services.” The committee said student retention and loan repayment rates were among the worst it had seen, and the report concluded, “Although the majority of students leave the company’s schools with no degree or diploma, the company also receives increasing amounts of Federal taxpayer dollars and profit.”

* * *

Shortly after Easley spoke to the 911 operator that Friday morning in July, the Cobb County Police Department showed up in force. They closed Windy Hill Road to all civilian traffic. They made sure those sheltering inside the Popeye’s, the Waffle House, the Wendy’s, the Subway, and the Chick-fil-A all knew to keep clear of the windows in case a detonation shattered the glass. The fire department was dispatched to the scene, as was the bomb squad, SWAT team, crisis negotiators, and a K-9 unit. Officers of the Sheriff’s Department handled traffic duties. Representatives from the Marietta PD, the ATF, the FBI, and its state equivalent, the GBI, turned up as well.

Register arrived within the hour, taking up a position at the makeshift command post. Solidly built, with a tree-trunk physique and wispy brown hair fading to gray, Register was viewed by community leaders as a reformer. The incident at Windy Hill Road would be his first test.

Meanwhile, inside the bank, Easley was getting a crash course in how TV news gets made. WSB-TV boasts one of the top local news organizations in the country: In the June ratings period, the station had attracted nearly two-thirds of TV news viewers in the metropolitan Atlanta area. Now, the staff had landed an incredible scoop simply by picking up the phone, and they knew it. On an audio recording of the call turned over to the GBI, one can hear the assignment editor’s colleagues scrambling to press their advantage. As she works to nail down what to Easley must have sounded like trivial details (“You said you had lived in Marietta previously, when did you live in Marietta?”), it seemed to dawn on him that her interest lay less in solving his problem than in working the story. “Okay, ma’am, I’m sorry,” he finally said, “but I’m about to wrap this up.”

As the call ended, two of the editor’s colleagues could be heard discussing how to proceed. “What can I report?” one asks. The exuberant reply: “Everything!”

Sometime after 11 a.m., Sgt. Andre Bates, the incident’s lead crisis negotiator, settled into a black Ford Taurus at the Texaco. He took a deep breath and dialed the number given to him by the 911 operator. Bates — who, like Easley, is black — established a rapport with the hostage taker almost instantly based on their shared military background. “I’m going through it with Veterans Affairs myself, so I know it can be difficult when they drag their feet,” he said.

Their status as former Marines further cemented the bond. “Semper Fi, sir. I’m a West Coaster, MCRD San Diego,” Bates said. “What can we do to resolve this, sir, and help you out? From one Marine to the other?” Although only Sgt. Bates’s side of the conversation is audible on the recording, his skills as a negotiator are evident. He gets Easley talking about his back injury and mentions his own knee and ankle issues. He assures Easley nobody is going to get hurt: “That’s my responsibility — to make sure you stay alive.” He compares the police force to the Marine Corps and engages Easley as a fellow enlisted man. “I have three of my chiefs that are personally here . . . guys walking around with stars just like it is in the Marine Corps . . . they’re not happy,” he said. “Just asking from one Marine to the next — to show that you and I are communicating and we’re on the same program — could you release one of those ladies, please?” And he appeals to Easley’s personal dignity, reminding him, “Your honor is worth more than the $892 the VA owes you, sir.”

Around noon, Easley agreed to a deal: A pack of Newports in exchange for one of the hostages. He seemed to mean it. As soon as he got off the call, Easley turned to his two captives and invited them to decide which one would leave. They told him they couldn’t choose. “Well, you’re just the teller,” he told one, “so I’ll let you go, and I’ll keep the branch manager here so they won’t blow my head off.”

The deal marked a significant breakthrough. They were working together now. A resolution seemed well in hand. In a brief interview, Sgt. Bates expressed absolute confidence that Easley would have honored his side of the bargain. “We were brothers who had bonded with each other,” he said. “I felt that me and him had connected as men, as Marines, and as family men.”

Bates hustled over to brief his superiors in the mobile command center, a large RV parked nearby. Among them were Register and the incident commander, Maj. Jeff Adcock. Reporting to him were Lt. Joel Preston, another Marine veteran, who commanded the tactical team, and Lt. Jorge Mestre, the crisis team commander.

It was a formidable group, with decades of experience. Mestre was a key figure in a 1999 incident in which he was wounded after trying to reason with a local man who was reportedly suffering from paranoid delusions. After opening fire on the officer, the man barricaded himself inside the house with his aging mother and later killed two members of the Cobb County SWAT team after they stormed the family home. The tragedy is viewed as a critical lesson among tactical-policing experts, who blamed the incident on poor intelligence and inadequate staffing, revising standard procedures accordingly. For some members of the Cobb County PD, the killing may have carried an additional lesson: In a barricaded subject situation, avoid unnecessary risks.

As Adcock and the other commanders quickly began hammering out a plan to deliver the cigarettes without endangering their officers, they had good reason for optimism. According to Chris Grollnek, a former SWAT officer who now provides training in dealing with active-shooter situations, “Ninety-nine percent of the time, when a negotiator is making a deal for one thing for another, the incident ends peacefully.”

Around the same time, another opportunity to end the standoff safely presented itself. One of the hostages who’d been on the phone with the police throughout much of the morning reported to Officer Christopher Few, Bates’s colleague on the crisis negotiation team, that Easley had gone to the bathroom. He was in there for more than a minute, it seemed, long enough for both hostages to potentially run out the doors. Once Few understood what was happening, he began to walk the hostage through an escape plan. But seconds later, Easley returned. “He’s out,” she said quietly.

Meanwhile, along the wood line, the snipers lay on the ground, squinting through scopes at the action inside the bank. One of them, Officer Ponte, had also served in the Marine Corps, working as a helicopter crew chief before his discharge in 1992. On assessing the situation, he’d selected a Lapua .338, a $5,000 semiautomatic rifle billed as “The Long Arm of the Free World,” and loaded it with Sierra MatchKing .338 250-grain ammunition, a combination he felt certain would have the power to penetrate the two glass doors and still maintain its trajectory. Then he’d aimed his laser at the building and noted a range of approximately 66 yards. Every once in a while, as he peered through the scope, he got a good visual of the man in the gray sweatshirt. He radioed Lt. Benjamin Cohen, the assistant SWAT commander, and advised him that he had a clean shot. Should he engage the threat, he asked. Word came back: “Not at this time.” The rest of the tactical team was not yet in position. Stand by.

Minutes passed. On the SWAT team’s radio frequency, Ponte heard indications that a hostage might be released, but from what he could see, he later told the GBI, “There was no effort or energy being put forth toward releasing somebody.” Then Ponte made a fateful decision.

Around 12:15 p.m. on July 7, a single shot rang out on Windy Hill Road, ending the three-hour ordeal in the Wells Fargo and adding Easley’s name to the list of 236 mentally ill people killed by police in 2017.

* * *

Not only were Sgt. Bates and the various commanders caught off guard by Ponte’s action, his fellow SWAT team members were as well. In a well-planned operation, the tactical team would have reacted instantly to the gunshot. Instead, nine long seconds ticked by before an officer put the CCPD’s BearCat armored vehicle in drive and began barrelling toward the door of the bank, inadvertently endangering the hostages, who were just then preparing to dash out in the opposite direction. After the BearCat struck a column and backed up, its hood covered with broken bricks, the hostages escaped, and members of the SWAT team hustled them into the back of the vehicle, which quickly reversed away from the bank.

The standoff was over. But exactly what happened to Brian Easley — and who made the decision to kill him — would remain a mystery for months. Addressing the news media shortly after 1:30 p.m., Register incorrectly framed the incident as an extraction operation gone awry. “We had a SWAT team, tactical team, move up on the bank to help get the hostages out,” he said. “During the extraction process, contact was made with the suspect, and it appears the subject is deceased.” The explanation seemed to imply that Easley had been shot during some kind of confrontation with the entry team rather than by a sniper hidden in the woods. No mention was made to the public of Bates’s negotiations with Easley to release one of the women for a pack of smokes. Although the entire command team knew of the arrangement — as did the two hostages and other members of the CCPD — it is only being made public now as a result of an open records request.

Barricaded-subject incidents, especially those involving hostages, are among the most difficult circumstances police officers face. Typically, attempting to negotiate a peaceful resolution is the preferred approach, with a tactical assault reserved as a last resort. But the balance between crisis negotiators and SWAT elements is a delicate one. Negotiators are trained to strike up a rapport with a suspect, calm them down, and appeal to their sense of reason. Tactical officers, increasingly outfitted with military-style gear, are primed to take swift, decisive action.

The Cobb County Police Department’s internal Policy Manual states that in a hostage situation like the one at the Wells Fargo, a tactical solution must only be initiated “should communication with the subject fail to resolve the incident,” and that “the ultimate decision will be made by the On-Scene Commander.” In the case of Brian Easley, communication was making genuine progress, and the On-Scene Commander, Major Adcock, had decided to let the negotiations play out. According to Ponte’s own testimony, he made the ultimate decision himself, an apparent violation of both policies. He cited no particular action on Easley’s part — an erratic movement or aggressive gesture, for instance — that might have indicated an elevated risk. When I reached him for comment, Ponte declined to speak except to say that his side of the story would be told “at the appropriate time.”

Sgt. Bates, the crisis negotiator, refused to criticize the actions of a colleague and fellow Marine. But asked whether he’d been sincere when he’d promised Easley that nobody would hurt him if he cooperated, Bates told me, “I meant that from the bottom of my heart. I’m out there to do a job. I’m pretty good at what I do, and the things I’m telling him are coming from the heart, one human being to the next. My job is to protect everyone so we can all walk out of there and play out whatever happened in court. That is the win for me.”

All of the experts I contacted were careful to emphasize they lacked a complete picture of what happened, and they expressed reluctance to second-guess CCPD’s handling of a dangerous and chaotic situation. They agreed, however, that the decision to shift away from a negotiating posture and initiate a tactical operation is not typically made lightly or based on the judgment of an individual officer, and that the situation on Windy Hill Road might well have concluded peacefully had negotiations been given more time.

Easley “articulated he’s not going to do anything to harm the hostages, so that’s a great sign,” said Randall Rogan, a crisis negotiation expert and co-interim dean of communications at Wake Forest University. “If a suspect is emotionally calm at the beginning of a siege or incident, that is the most critical moment.” He added that Easley’s demands were extraordinarily modest. “He’s not asking for a helicopter and $2 million dollars and taking two hostages on a plane.”

“Easley was very calm, he indicated wasn’t looking to hurt anybody, and he demonstrated a willingness to cooperate,” noted Jack Cambria, a 33-year veteran of the New York City Police Department who spent more than a decade in tactical operations and, later, as commander of the NYPD’s crisis negotiation squad, responded to more than 4,000 incidents. “Tactical assault is reserved for the last option, when it becomes absolutely necessary.”

Following a grand jury hearing, Ponte was cleared of any wrongdoing in connection with Easley’s death. District Attorney Vic Reynolds told WSB that the officers “followed the law and did what they were supposed to do.” According to the policy manual, “ability, opportunity and jeopardy” must all be present for a shooting to be justified. As far as anyone knew, Easley had the ability to cause harm to the hostages with a backpack full of explosives. He had the opportunity to do so. And the hostages were plainly in jeopardy.

Cambria, who trains law enforcement agencies around the country in crisis and hostage negotiation, agreed that Ponte likely acted within the law. Nonetheless, he pointed out, “Just because an action might be lawful doesn’t mean it was necessary.”

The operation appears to have been flawed in several additional respects. Given Ponte’s testimony that the hostages were not in sight when he opened fire, he ran the risk that one might have been injured by debris or a wayward bullet. A poorly aimed round might have set off the explosives Easley claimed to have in the backpack, mere inches from where the shot made contact. And there was one more possibility to consider: “When there are people alive near the subject, you very rarely will take a shot to neutralize him in the event that God forbid, he has a dead-man’s switch,” Grollnek said, referring to a detonator wired to explode if a trigger is released. Such devices, which work like a hand grenade, are simple to engineer. Had Easley been using one, Ponte’s shot could well have caused the deaths of the hostages. Finally, the haphazard extraction of the two captives also indicated that the decision to act may have been taken too hastily.

As the hostages were whisked to safety, a robot entered the bank and retrieved Easley’s backpack, placing it in a “total containment vessel.” It was eventually deemed harmless, and inside investigators found a Bible, some papers, and a small machete, among other incidentals. (Easley had never taken out the knife or mentioned having it, and Calvin later suggested he may have been carrying it for protection.) On his body, they found a wallet, a broken cross pendant, and an electronic device one hostage had assumed was a switch to detonate a bomb. In fact, it was a tool for detecting hidden listening devices, perhaps a prudent purchase for a man suffering from the paranoid delusion that he might be kidnapped at any time.

Before long, patrons of the nearby establishments, who’d been on lockdown all day, were finally allowed to go about their business. After being interviewed by police and GBI agents, the two hostages went home to their worried families. The local news teams packed up their gear. Easley’s body was taken to the Cobb County’s Medical Examiner in Marietta. Chief Register addressed the media and then headed back to headquarters. Traffic on Windy Hill Road resumed in both directions.

* * *

The killing of Brian Easley was just the first of several crises to engulf the Cobb County Police Department in the early months of Register’s tenure. In late August, WSB aired bodycam footage from November 2016 in which Officer James Caleb Elliot is seen firing multiple shots at the back of an unarmed teenager as he flees through a residential neighborhood, striking him in the leg. A grand jury declined to recommend charges against Elliot, and DA Reynolds noted that officers pursuing a fleeing suspect in a “violent, forcible felony” are allowed to use lethal force. The fact that the teenager was not actually involved in a carjacking was viewed as immaterial since the officer merely had to believe he was.

The new chief, for his part, indicated that legalities aside, the shooting endangered the public, and he used the release of the video as an opportunity to initiate additional use-of-force training. He also noted that the department recently purchased a new simulator to better prepare officers to handle such situations. Elliot left the force three weeks after the shooting, and a lawyer for the victim announced plans to file a federal lawsuit.

Then on August 31, Channel 2 released another dashcam video, this one from the summer of 2016. In it, Lt. Greg Abbott, who is white, is heard remarking to a white motorist, “Remember, we only kill black people.” Though many observers pointed out the officer’s sarcastic tone, the starkness of his statement at a time of heightened concern over police shootings of African Americans (the killing of Philando Castile outside St. Paul, Minnesota, had happened just four days before the traffic stop) seemed emblematic. The video went viral. National outlets picked up the story. Representatives for Al Sharpton’s National Action Network told Register a protest march was being organized. Register’s office was bombarded by media calls from as far away as the United Kingdom. This time, Register moved swiftly, announcing that Abbott would be terminated.

“It’s been one of those weeks in Cobb County,” Register told me with a sigh not long after. The decision, he said, had not been easy. But Register was unmoved by the argument that Abbott had been trying to gain the motorist’s compliance by creating a casual rapport, calling the statements “inexcusable and inappropriate” and “not indicative of the values and the facts that surround the Cobb County Police Department and this county in general.”

A vocal contingent within the CCPD expressed unhappiness that he hadn’t defended Abbott. “They took it as me not supporting them,” Register said. After a local talk radio jock went after him — taking care to inform listeners that the police chief’s wife is African American and even noting her place of work — white nationalists went on the offensive, sending Register hate mail in which they called him “a disgrace to the white race.”

Following the decision, Register scheduled a set of mandatory staff meetings in which he laid out his rationale for demanding Abbott’s ouster. The radio station apologized. Eventually, the controversy seemed to die down. Still, it was clear the job was weighing on him. “I’ve got to tell you,” he admitted, “sometimes I’m like, ‘Damn, maybe I should have stayed in Clayton County.’”

* * *

The tendency of police departments to close ranks in an effort to shield their actions from public scrutiny is well established and perhaps unsurprising. The same “blue brotherhood” that bonds law enforcement officers can easily slip into a form of tribalism when a member of the team is under threat. The commitment to one another that keeps officers alive in dangerous situations also seems to discourage self-reflection when things go wrong. Initially, after I asked Register about the killing of Easley, he mounted a strong defense of Ponte. “He saw this thing unfolding and felt that this might be the only chance to immobilize the suspect and save the two women, and he took it,” Register said. “If we would have waited five more minutes, and he had detonated explosives and killed himself and the two hostages, then we may have be having a conversation — ‘Now, why did we wait so long?’”

Register also emphasized that Ponte — who was cleared by a grand jury following another fatal shooting in 2016 — had struggled in the aftermath of the Wells Fargo incident. “One reason why it’s been so hard on this young man who took the shot,” he said, “is that he is a veteran himself and a Marine. It’s very hard on him. It makes you want to cry.” (Although Register repeatedly spoke of his officer as a “young man,” records indicate that Ponte was born in 1966.)

A month later, when I pressed Register about the revelations contained in the GBI report, which he indicated he had not yet seen, he reconsidered his position. While reiterating that the shot was legal, he said, “I do call into question the timeliness of it.” He also said he’d be looking into the apparent breakdown in command and control, explaining that he would “dig deeper and ensure that if there were any issues that created the desynchronization between the negotiating team and the tactical team that we address that and we fix that. Certainly, as the event was unfolding, I don’t know if the communication was transpiring as quickly as it possibly should have.”

The next morning, Register called back. He mentioned an additional change he’d implemented a few months before, a monthly training session with his incident commanders to do “tabletop exercises,” reviewing some of the scenarios they might face in the field. He added that he’d been up half the night digging into the reports on the Easley shooting, and he’d scheduled a weekly meeting with his leadership staff to talk about developing a procedure for identifying mistakes so they won’t be repeated. “We have to take some time to look at what the findings were and come back for after-action reviews,” he said. “That’s the only way we were going to be better.”

* * *

Whatever mistakes may or may not have been made on Windy Hill Road on July 7, there’s one issue about which everyone seems to agree: Brian Easley himself bears a good portion of the blame. Even when one takes into account his mental illness and the other formidable struggles he was facing, the fact remains that Easley alone made the choice to enter the bank, claim he had a bomb, and hold two women against their will.

“I’m sorry for what happened,” Calvin Easley told me when I visited him and his wife, Anita, in their tidy home in the Atlanta suburbs. “I’m sorry he went in there and took hostages. I’m very sorry for that. He was not in his right mind. But they didn’t have to kill him. He just wanted to get his story out.”

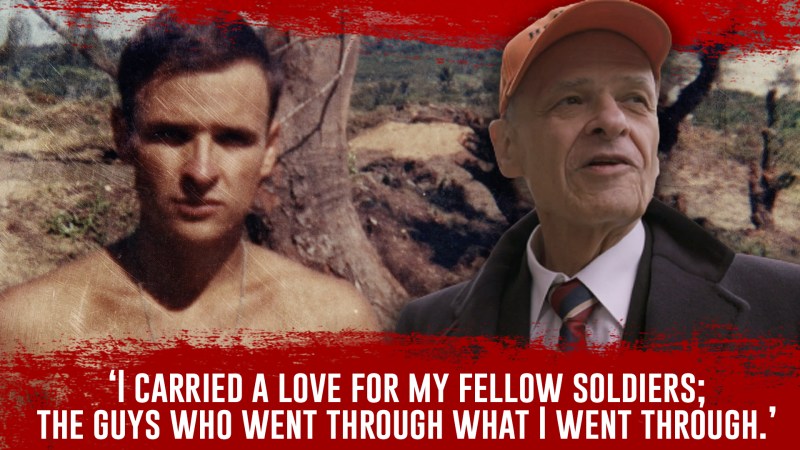

That story is one that many veterans can relate to. The same military experience that helped make him a man left him anxious, troubled, and eventually unable to work. Perhaps for the first time in his life, he discovered a sense of brotherhood and meaning in the Marine Corps, one he was unable to replicate once he returned home.

But Easley did what he could. He cared for his daughter, calling her every day and sending gifts when finances allowed. He battled the VA for years to receive the benefits he’d earned through his service. He sought an education, hoping to start a career, support his family, and make a new life, only to find himself in a trap that has ensnared thousands of his fellow veterans.

Then, one morning in July, he woke up to find that the money he counted on to make it through simply wasn’t there. And just like the Marine Corps had taught him, he took initiative. He called the hotline. When they hung up, he called again and again. Finally, he walked into the benefits office to plead his case in person. But instead of recognizing a veteran in crisis and working out a plan, or perhaps directing him across the street to the hospital, writing a prescription, and getting him back on track, they sent him away in search of paperwork.

“The problem was bigger than the Cobb County Police Department and Mr. Easley,” Bates told me. “The problem is the system — how they treat retired veterans. You should get more than ‘I appreciate your service.’ The VA owes these guys more. They’re willing to put their life on the line for their country, and when they separate from military they deserve better.” In particular, he criticized the VA’s decision to handcuff Brian Easley rather than help him. “That’s where the whole thing went bad, I believe,” he said.

“I’m just baffled about what is so hard to negotiate,” said John Delorme, a Marine who served with Easley. “This isn’t a terrorist. This is a guy who fought against terrorism. As a veteran, it makes me feel smaller than a grain of sand, the way he was treated.”

“I just don’t want his little girl to grow up to think her dad was a bad person,” said Ian Emmett, another battle buddy. “He was a good person.”

Alecia Miller, who dated Easley for two years when he was in the military, agreed. “I hate for him to be painted as this crazy deranged person,” she said. “This is someone who the system failed, and because of that, a decision was made out of desperation, and someone has lost their life because of it.”

“You go over there and you fight a war for our country and everybody’s out to kill you,” Calvin Easley told me. “You don’t know nobody. You’re in a foreign land. But the real sharks? The real sharks are back at home. There’s no reintegration. You don’t get support from the country that you fought for.”

It was late. Anita stood behind him as he spoke, patting his back. “I’m livid,” he went on, fighting back tears. “He was a hero. He was not some psycho on the corner. He was not. He was a gentle giant until you pushed him. If you pushed him to the max, then you’d see a different person. But it took an awful lot. It took a lot.

“I know this,” he said. “He was my brother.”

This article was published in collaboration with the editorial team at Longreads.

The latest on Task & Purpose

- Opinion: In the name of health care freedom, millions of veterans may lose theirs

- Special Forces vs special operations forces — what’s the difference?

- Commandant wants all Marines to do a tour in the Indo-Pacific

- VA claims processors overwhelmed, quitting from high case load

- First photos of 101st Airborne soldiers testing the Army’s new rifles

![Someone hijacked a Navy warship’s Facebook account so they could livestream ‘Age of Empires’ [UPDATED]](https://taskandpurpose.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/06/uss-kidd-feature.jpg?w=800)