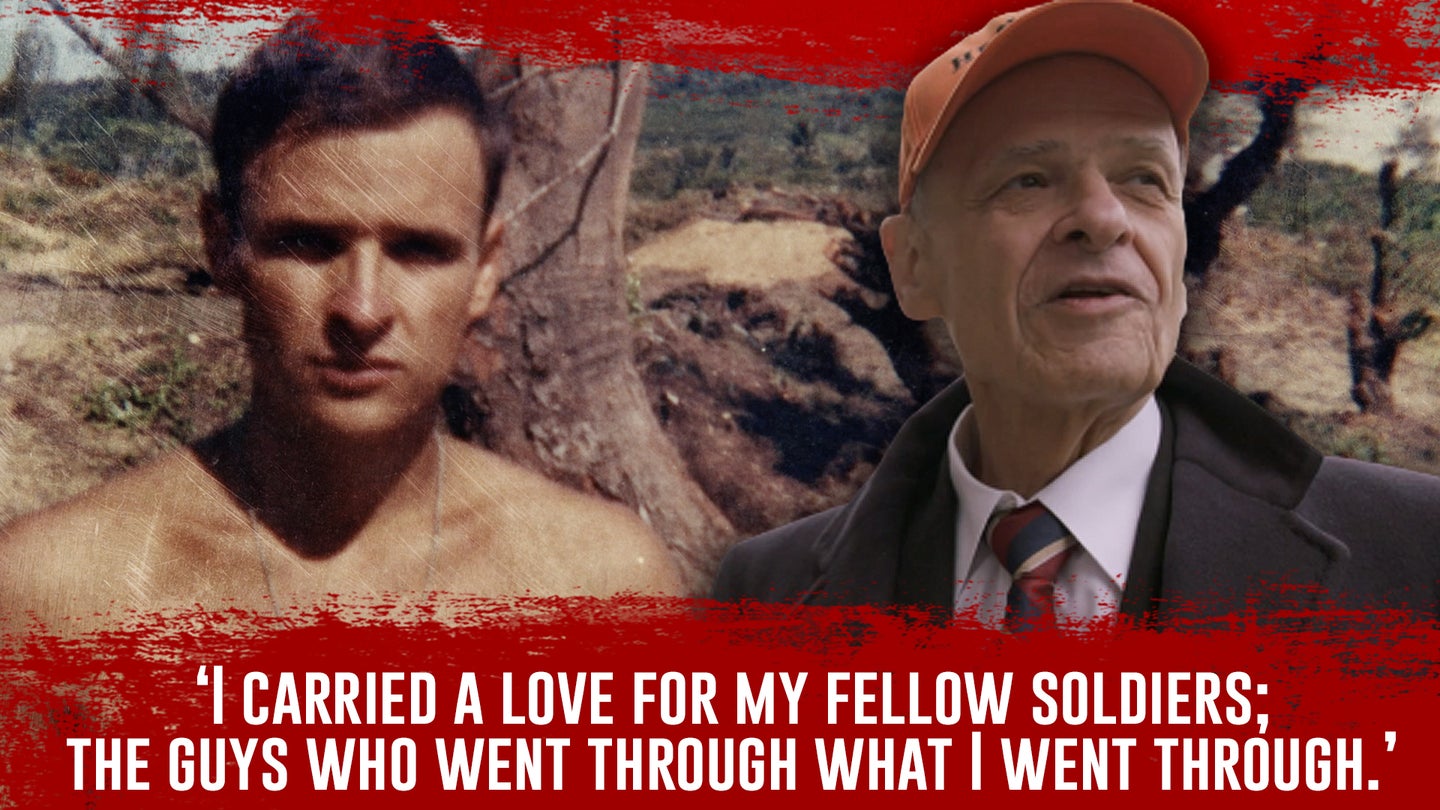

The acclaimed author of ‘The Things They Carried’ tells us what he carried in Vietnam and carries with him still

An M16, letters to a girl, fear, pride, love. He's left some burdens behind in exchange for others.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published on Feb. 18, 2021.

Tim O’Brien is many things. A Vietnam veteran. A Purple Heart recipient. The so-called “poet laureate of war.” One of the greatest American writers of his generation. He is all those things and many more. He’s a loving father and husband. A devoted teacher, not just to his sons, but to his students at writing seminars, some of whom are military veterans looking to share their stories of war, and in so doing, make sense of their own experiences. He’s a fierce and unrelenting critic of unjust wars; a crusader against apathy and willful ignorance; and a preacher for peace who wields his rage and eloquence like a weapon against those who call for blood but are never there on the ground when it is spilled.

Though he has written many novels over the years, O’Brien is perhaps best known for The Things They Carried, a collection of fictional stories which drew heavily from his own experiences in Vietnam as a young 20-something infantryman who was drafted into the war in 1968. The novel’s unique framework — revealing the hidden depths of individual soldiers through their burdens, both literal and figurative — has captured the attention and imagination of millions of readers, many of them veterans, and even inspired a recurring series on Task & Purpose.

We recently spoke with the acclaimed author about The War and Peace of Tim O’Brien, a documentary by Aaron Matthews that chronicled O’Brien’s struggle to finish one last book, and in the process revealed the many ways that art, family, duty, and trauma intersect in our daily lives. During that interview, we took the opportunity to ask O’Brien what he carried in Vietnam, and what he carries with him now.

The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity and style.

Task & Purpose: What did you carry in Vietnam?

Tim O’Brien: I carried all the standard military stuff: grenades, ammo, an M16, sometimes an M60. Letters from mom, dad. Letters from a girl back home.

More than the physical, I carried incredible terror with every single step I took. Is the land going to blow me up? I think of that all the time, even when I walk out of the house. To this day, I watch the pavement, the grass. It’s just been built into me.

Indeed, O’Brien specified many of the dangers he faced in Vietnam, ticking them off one by one: Land mines, booby-trapped artillery rounds, bouncing betties, toe poppers. “85 percent of our casualties came from land mines, which you couldn’t shoot back at,” he said. “So it felt as if the whole country was just killing us. The ground, the trails, the paddy dikes.”

I carried a sense of responsibility for the deaths of other people, and it wakes me up at night. And I carried a love for my fellow soldiers; the guys who went through what I went through; who didn’t shoot themselves in the foot, as everyone was tempted to do but very few did. You just kept humping forward, every day. There’s something grand about that, knowing that just walking can kill you, but every day you set out, and keep your legs moving. There’s a pride in it. As much as I hated the war, as much as I disagreed with it, I kept humping and so did the guys around me and that’s the thing I carry inside me to this day.

What do you carry now?

I carry the love of my children and my wife.

I carry the increasing burden of my own mortality: I’m 74 years old, and in the next 5, 10, 15 years I’ll be dead. I carry a kind of urgency inside of me: Get this done, get that done.

Part of this is a kind of wrapping up of a life: One more book, maybe? One more trip to the Bahamas, maybe? One more quiet dinner with my family, maybe? There’s an endless maybeness to the world now that didn’t used to be there. It does come upon all of us, I’m not special in that way. It’s a lot like being back in Vietnam when I was 22; Maybe I’ll have the next 5 minutes? Maybe I won’t. Now it’s back again as an old man. Maybe there’ll be a tomorrow? Maybe there won’t be a tomorrow?

So, I’m carrying that now.

What do you carry for personal significance? For example, how about the hats you always seem to wear?

On our plane ride home from Vietnam, as we came in to Seattle, it was night and I went into the back of the plane and the lavatory and I took off my uniform and I put on blue jeans, a sweater, and a baseball cap, and I’ve been wearing a ball cap ever since then as a kind of reminder to myself that I’m a human being. I’m not a guy who belongs in a uniform. I hated it. I hated saluting my inferiors.

After saying “inferiors,” O’Brien paused to ask if I had been an officer — I told him I had not.

Some officers deserved it, a lot of them didn’t. I hated having to say “yes sir” to stupidity, to ignorance. I hated it. [But] the baseball cap — I have one on right now — it’s a reminder of that day I got off that airplane in Seattle and rejoined the civilian world.

More great stories on Task & Purpose

- Army finally reveals why a soldier is being court-martialed for a mysterious firefight in Syria

- ‘We need to wake up’ — Air Force Chief Bass calls out critics of ‘woke’ culture

- This Marine officer wants to charge a general with ‘dereliction of duty’ over Afghanistan. (He can’t)

- US troops are still in Syria and nobody can give a good answer as to why

- How Mark Milley became America’s most politicized general

- ‘You blessed us with light and love’ — America welcomes baby girl of Marine killed in Kabul

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Learn more here and be sure to check out more great stories on our homepage.