A toxic culture of gender discrimination and inequality continues to exist in the U.S. military. Worse, it isn’t simply gray-haired military bosses who are responsible for this. The atmosphere created by a few junior military personnel can ruin the career of a promising servicewoman before it even begins.

I know this because I have seen it happen.

When I was a brand new officer, fresh from Navy flight training, I met my first command while they were on deployment in the Persian Gulf in 2011 aboard an aircraft carrier. Six months into an eight-month deployment, they hated everyone and everything — including me, the newly minted lieutenant junior grade stepping off the C-2A Greyhound for the first time.

They especially hated a popular woman officer in our squadron. This woman just naturally got along with nearly everyone. She was competent, capable, and energetic. Two years my senior, she was a role model to me.

The onus is on us — the young men of the officer and enlisted corps — to come together and say, “Enough.”

Unfortunately, a small but concentrated segment of male officers in the squadron resented her popularity. They made it their mission to make her life a living hell. In activity that never rose to the level of criminal, to my knowledge, they kept tallies of how often they made her cry, talked about her behind her back like she was unintelligent or promiscuous, and undermined her at every opportunity with senior leaders around the ship. It was nasty, and it was constant.

As an inexperienced member of the command, I was conflicted. Thrust into a new situation halfway around the world, I had to achieve my Navy qualifications, take care of my sailors and collateral jobs, and try to learn how to be an effective member of a team flying in support of combat operations. I was exhausted, demoralized, and just trying to hang on.

But the behavior of the offending men was a daily occurrence, and it floored me each time. I was repeatedly faced with a choice: Stand up and speak out, or sit down and shut up.

So what did I do? Not much. I hid. I thought that surely someone senior would take care of it. In private, when it was just a small, safe group, I would express how jacked-up I thought things were. There were a handful of junior and more senior officers who felt similarly, but I didn’t do anything in front of the offenders. I demurred; I hesitated.

Gradually, as the culprits left the command and the small group of us rose in seniority, we tried to make right. We made sure every new person to the command knew what had happened and how unacceptable that kind of behavior was.

Too little, too late, unfortunately, for the targeted officer. Her career might not have been cut short as a direct result of these events, but it was certainly affected. And now there isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t think about how I was silent when it really mattered.

Across the services, women are targeted and discriminated against, not for their tactical or technical acumen, not for their ability to do their job, but simply because they are different.

In any workplace, discrimination of nearly one-fifth of the workforce would be shocking. In the military, it is indefensible. Discriminating against instead of developing servicewomen negatively impacts military readiness, hampers our ability to accomplish the mission and win, and wastes taxpayer money. Most importantly, gender discrimination is objectively wrong and a stain on military services that claim to value concepts such as honor, integrity, and accountability.

Today, as women come forward with horrific stories of violence and discrimination both inside and outside the services, what we need in our ranks is clear: more allies, fewer adversaries.

Being an ally is instrumental to overcoming not just the overt acts of cruelty that I witnessed, but also the insidious creep of unconscious bias. Each one of us confronts the world by subtly categorizing, ranking, and valuing those around us. Each one of us harbors internal stereotypes, ascribes certain values, and pre-plans emotional responses based on these categories. Whether we realize it or not, these unconscious biases reflect how we behave every day. In the long term, these biases affect how we lead and mentor, and ultimately, shape the careers of others.

Being an ally means recognizing our unconscious bias and advocating for others. Too often, our wardrooms and messes fall prey to the “ducks pick ducks” mentality, where we reward those who seem most like us while shunning those alien. Being an ally in practice means mentoring and advocating for those who are different as a matter of principle — and it means speaking up when others attempt to throw up roadblocks or poison command culture based on those differences.

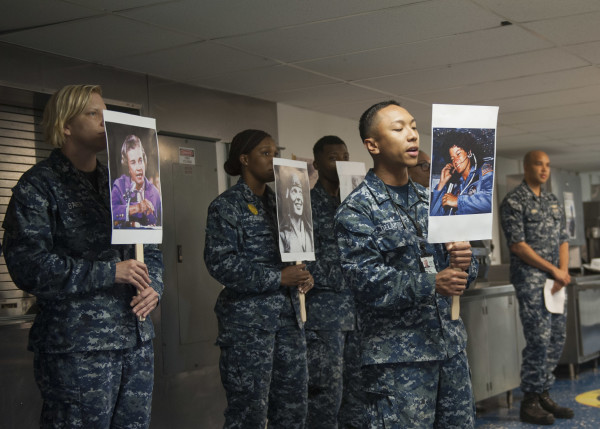

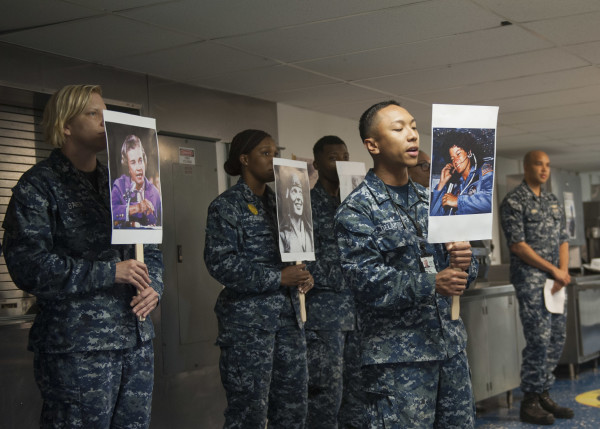

An all female Honor Guard presents the colors at the 16th Annual Veterans Parade November 5, 2016 in Boise, Idaho.U.S. Air National Guard Photo/Tech. Sgt. Sarah Pokorney

Crucially, however, the preponderance of allies must come from our junior officer and enlisted personnel. We cannot stem the tide of gender discrimination in the armed forces without a groundswell of young men speaking up, calling out injustices, and standing shoulder-to-shoulder with our women colleagues just as we do with any of our other comrades.

How does this look, in practice? Helping women through training and qualifications, just as we are helped by our own mentors and lifelines. Speaking up when we are awarded or recognized to say, “actually, this was her.” Swallowing our pride and standing up to sexually suggestive or destructive jokes targeting women in the ranks. Advocating for women to achieve the most coveted operational positions in our Navy — and then putting in the work ourselves, without having to be coerced, to help them succeed.

The onus is on us — the young men of the officer and enlisted corps — to come together and say, “Enough.” We cannot rely on senior leaders to tell us to do the right thing or implement mandatory military training. We must create a culture that ends gender discrimination and violence. We must become allies for military women for the sake of our service, our honor, and our country.

Roger Misso is a naval officer. He is also a speechwriter, husband, father, and aspiring 50-state marathon runner. He is a graduate of the US Naval Academy, Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron ONE (MAWTS-1) and the Harvard Kennedy School.