Veterans And Pro Athletes Face Similar Challenges Returning To Normal Life

Many service members and athletes find that their careers become their identities. Once it comes time to transition, however, the...

Many service members and athletes find that their careers become their identities. Once it comes time to transition, however, the return to normal, daily life can seem impossible.

The drive that stems from teamwork in both the military and in sports is one that is not understood by most people.

“When they go to war or when they do exercises, they work as a team,” former NHL player Clint Malarchuk said in an interview with Task & Purpose earlier this year. “With that team you develop that camaraderie. We’re all the same that way. I think that’s what you develop in a team atmosphere, both in sports and in the military, so there are a lot of parallels.”

Malarchuk found that veterans understood what he was going through post-career better than others could.

“For me … the things that I struggled through my life with trauma and mental illness, opening up when I talked about it and everything, these guys they absolutely relate,” he said.

Like athletes, veterans have specific training and less formal education. The mission is their life in the same way that playing is everything in professional sports. When it comes time to retire, both athletes and veterans struggle to find meaning in their everyday lives.

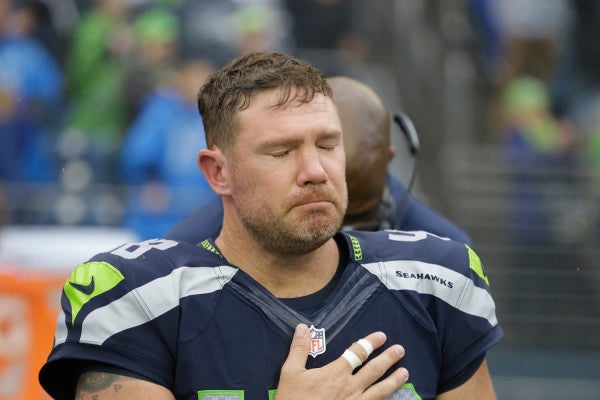

In an interview with Task & Purpose, Nate Boyer, former Army Green Beret and NFL long snapper for the Seattle Seahawks, said, “You had that high sense of purpose, and now it’s gone.”

With his transition, he said it was less difficult because he had something to look forward to moving forward.

After switching from active duty to the National Guard, Boyer immediately enrolled at University of Texas and was able to walk on to its football team.

“That’s the biggest problem I think with guys who are transitioning. They wait until they’re out, and they’re kind of like, ‘Now what?’” Boyer said.

Whether it is a veteran or a professional athlete in transition, there needs to be a new mission or a goal to work for, he added. Veterans and athletes have a hard time being told to go get regular jobs and have a regular life.

“We’re different,” Boyer said. “We’re built different, we’ve overcome insurmountable obstacles, survived things other people can’t even dream of.”

Though he is currently an NFL free agent after being released from the Seahawks, he is not worried because he has a new missions: continuing to serve others.

He encourages other veterans to do the same.

Boyer recently began helping with a program called “MVP” or Merging Vets + Players — a program started by longtime sports journalist Jay Glazer to help both veterans and former athletes get their lives back after transitioning.

Because athletes and veterans have a mutual respect for one another, looking up to each other as warriors and heroes, the MVP program leverages their shared experiences to allow participants to recognize that their military or athletic careers aren’t their sole identities.

The group holds retreats at the Unbreakable Performance Center in Los Angeles and Boulder Crest Retreat for Military and Veteran Wellness in Bluemont, Virginia, and the program has a signup page, open to all veterans and professional athletes.

Malarchuk said of his relationship with veterans, “These guys are the true heroes and warriors of life. I almost felt a little guilty as a player, because here’s guys sacrificing their lives and they don’t get the adoration that athletes do.”

Boyer, on the other hand, found that veterans too look up to their sports heroes.

“When I was a kid I wanted to be a pro football player, and a player sees this veteran as ,” he said. “So they both kind of revere each other in a different way.”

The MVP program, like a number of other transition programs, creates a place for people to overcome obstacles. It uses the common ground shared by veterans and professional athletes to create a space where they can both find meaning in life after transition.

Former Oakland Raider Oren O’Neal said in a feature in Fox Sports News, “Football was my identity. It decided when I went to bed at night, when I woke up, what I ate for breakfast, lunch and dinner, who did I hang with, where did I go. It controls so much of your life for so long, and now it’s gone.”

O’Neal credits the MVP program’s veterans with saving his life.

“Normally, our paths wouldn’t have crossed, but these guys helped me get my life back,” he said. “When they shared what they going through, I was like … a lot of this is the same thing I’m going through.

The thing that many participants in the program, whether veterans or athletes, said is that when they transitioned out, what they missed was camaraderie, a sense of purpose, and a sense of identity. Losing those things makes it very difficult to adjust to life after the military or professional sports.

Boyer encouraged those about to transition to find something they are passionate about before getting out. He added that because they’ve overcome trials and beat the odds in their careers as soldiers and athletes, a life without a mission will feel incomplete.

According to Boyer, if veterans and athletes want to find a sense of meaning again, “It’s got to be a challenge.”

Brian Adam Jones contributed to this report.