Drunk ideas, while entertaining, rarely end well. But there are exceptions. Like that time in New York in the late 1960s when a conversation about anti-war protesters led one veteran to set off on the greatest beer run in history.

It was November 1967, and a 26-year-old former Marine named John “Chick” Donohue was hanging out at Doc Fiddler’s — one of the many bars and pubs that dotted the neighborhood of Inwood, then an Irish-American enclave near Manhattan’s northern tip. The bartender, George Lynch, began complaining about the anti-war movement that had taken flight across the country.

For a lot of vets like Donohue, the marches and picket signs must have felt like a snub. So when Lynch suggested that someone go out there — to Vietnam — and bring those boys some beers to let them know they’re not forgotten, Donohue volunteered to go. And he went.

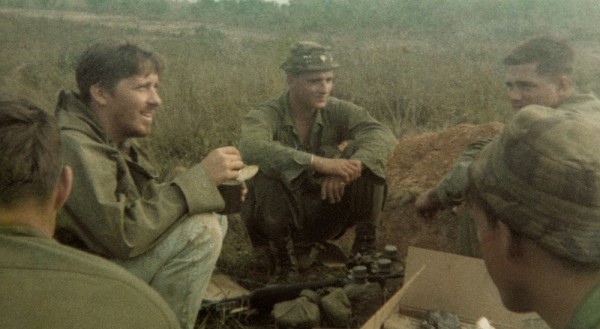

Chick Donohue, right, in Vietnam, delivering beer to a friend from back home.Photo courtesy of Chick Donohue

What followed was an 8,000 mile, four-month odyssey. Donohue trekked across a war-torn country, talked his way onto transport trucks and military aircraft, all so he could meet up with local guys from his neighborhood and bring them a cold — okay, lukewarm — brew.

“A lot of my friends were serving in Vietnam, and I just wanted to go over there and buy them a beer,” he candidly explained in a 2015 video short, in which Donohue met up with three of the servicemen he’d provided with beer in Vietnam: Bobby Pappas, Tom Collins, and Ricky Duggan.

Something of a local neighborhood legend, the story has often been met with eager but disbelieving nods of approval. To set the record straight earlier this month, Donohue, now 73, self-published “The Greatest Beer Run Ever: A True Story of Friendship Stronger Than War,” a book about his beer-hocking trek across Vietnam. Here’s how he got from a bar in New York to a warzone with beers in hand.

Donohue took a job on the next ship headed to the war, the Drake Victory, a merchant vessel transporting ammo to the ’nam from New York. He got the names and units of a half-dozen guys in the neighborhood, grabbed a seabag, stuffed it full of PBR, threw on a pair of light blue jeans, a plaid shirt, and headed out. Two months later, in early 1968, he arrived in Vietnam — just in time for the start of the Tet Offensive against U.S. and South Vietnamese troops.

Related: The Greatest ‘Hold My Beer’ Moment In American History Is Thanks To This Drunk Marine Veteran »

Donohue ran through his beer supply in transit, but stocked up when they hit port in Qui Nhon harbor. “It took two months to get there, so I drank all the beer,” he told the New York Times.

Shortly after pulling in, Donohue noticed the unit insignia on a group of military police officers who were inspecting the Drake Victory. They were from the 127th Military Police Company, the same unit as one of the names on his list: Tom Collins. Donohue, known as a smooth and quick talker, pulled one of the MPs aside and spun a sob story about looking for his brother-in-law, gave the man Collins’ name, and then waited. Not long after that, Collins arrived.

“I said, ‘Chickie Donohue, what the hell are you doing here?’” Collins told the Times. “He said, ‘I came to bring you a beer.”

After sharing a few drinks with Collins, Donohue set off to find the other names on his list. Donohue went from Qui Nhon, to Khe Sahn, then to Saigon, striking off names and handing out beers, then restocking.

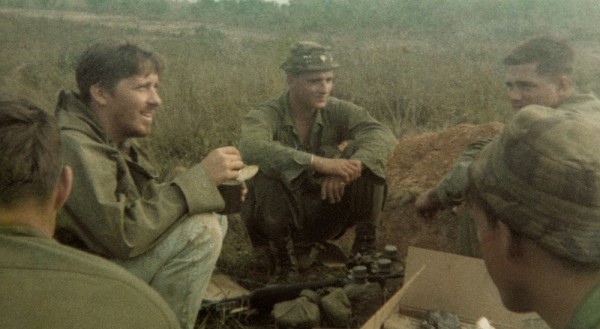

Chick Donohue delivering beer to soldiers in Vietnam.Photo courtesy of Chick Donohue

Donohue talked his way onto convoys, military mail planes, and transport helicopters. He even got caught in the Tet Offensive and was briefly stranded when his ship left port without him. So he hung around, caught up with his buddies on the front lines for a bit longer, and by March 1968, made his way back to Inwood where his beer run quickly became a local legend.

The beer was hardly the point, though. For guys like Pappas who had been having a tough deployment, after learning several old friends had died in combat, seeing Donohue, brews in hand, “gave me a lot of encouragement that I was going to make it back,” he told the Times.

“For half a century, I’ve been told I was full of it, to the point where I stopped even telling this story,” Donohue told the Times.

But even skeptics of Donohue’s story were happy to reward him for the deeper truth it contained. Back home in Inwood, he said, “I didn’t have to buy a beer for a long time.”