The bullet busted through his boot and pierced his heel. Fifty years later, he remembers how badly it burned.

Still, he was able to spot the enemy and give coordinates to two Cobra helicopters and the infantry. It was April 1969 in a firefight outside My Tho in the Mekong Delta region of Vietnam.

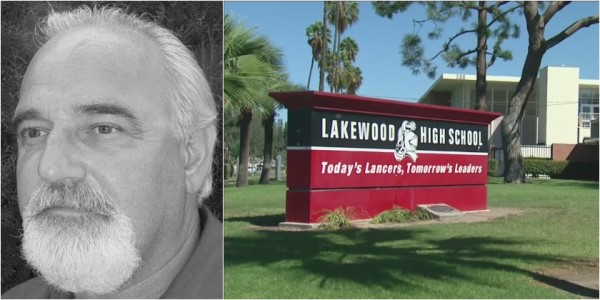

Ken Weiner, a Purple Heart and Air Medal with Valor winner, was 18 then. He still doesn’t sleep all the way through at night. “I get nervous,” said Weiner, who lives in Murrieta.

He is still fighting.

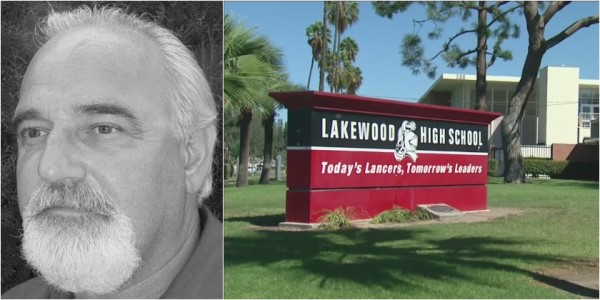

His battle today is for his pride, and his opponent is the Long Beach Unified School District.

Weiner has requested to receive a retroactive diploma from Lakewood High School, which he left during his senior year in 1967 to join the Army. Section 51430 of the California Education Code says school districts may grant diplomas to people who either were interned during World War II or are veterans of World War II, the Korean War or the Vietnam War if they went straight from school into military service (which Weiner did).

The code seems clear. Weiner met the second of those either/or criteria.

Another section of the code, Section 51440, says districts may grant a diploma to a veteran who “had satisfactorily completed the first half of the work required for grade 12.” Weiner dropped out of Lakewood High to enlist on Oct. 30, 1967, three months short of the halfway mark.

Weiner’s request has been denied.

“I’ve never asked for anything in my life,” said Weiner, who is 68 and is suffering from Parkinson’s disease. “The one thing I’ve asked for is this diploma.”

“It is my hope that you understand that we must adhere to the requirements that we are provided to follow by law,” wrote Carol Ortega, program administrator at the school district, in an email to Weiner dated Oct. 29. Ortega did not return phone calls asking for further comment.

It is not clear if the district interprets the code to mean Weiner had to qualify under both Section 51430 and Section 51440 rather than one or the other.

After questions from the Southern California News Group, district spokesman Chris Eftychiou wrote in an email: “We received your inquiry about the individual seeking a high school diploma. We do provide diplomas to former students who have met graduation requirements, but we cannot comment on individual cases.”

“I don’t understand why they’re doing this to him after what he’s been through,” said Laura Weiner, his wife. “It means a lot to him.”

The education code was changed in 2004 when Assemblywoman Sally Lieber wrote a bill to honor Japanese Americans who had been forced out of high schools and confined to internment camps. Lieber’s proposal also included veterans who had not received diplomas because they had left high schools to serve in the U.S. military.

Some school districts have reached out to veterans. In Sacramento, the district launched “Operation Recognition” encouraging veterans to get their diplomas. So far, 195 Japanese Americans and veterans have been given high school diplomas through the program.

Enlists at 17

As a kid, Weiner loved music.

He could play his guitar well enough at 15 to be sought after by local bands. He loved Elvis and the Rolling Stones. He grew his hair long, which irked his mother, so much so that she broke his guitar.

“My hair wasn’t even that long,” he said.

To protest the broken guitar, Weiner moved out of his family’s house at 15. He slept on the couches of friends for two years, working at McDonald’s and other jobs to pay rent.

At 17, he was bored with high school, so he dropped out and joined the Army.

“The first thing they did was shave my head,” he said with a chuckle.

Join the fight

Weiner trained at Fort Ord as a helicopter mechanic with 11 Bravo infantry. Those are the guys who fight on the front lines. During his training, he also did school work, completing his General Educational Development (GED) with the Military Institute of Education.

In June 1968, he was sent to Dong Nai, a province in Vietnam.

In January 1969, Weiner was sent into “an extreme firefight.” When his copter landed, he helped load 20 or 30 men with casualties.

When he got to the hospital, he was approached by a nurse.

“You’re bleeding,” the nurse said.

Weiner had shrapnel lodged in his forehead above his left eye.

“I had it removed, and I went back into the fight,” he said.

Awards, but no diploma

He played guitar at the base with his buddy, Thomas Grose, from Helena, Montana. They wrote a song together: “Crew Chief Sam.”

In January 1969, Grose’s helicopter was shot down, and he was killed.

“I helped pack his body up,” Weiner said. “Talking about it still makes me shaky. It still hurts. There are things that happened that you still can’t get rid of.”

In April, Weiner was in a helicopter flying low near the tops of the tree line when they were hit by enemy fire. He took a bullet to the foot.

“I felt myself get knocked back, and then it burned,” he said. He still walks with a limp.

In May 1969, Weiner was awarded the Purple Heart. President Nixon gave him a citation. He has a box full of medals on the wall of his Murrieta home.

Above the medals, there is a blank spot on the wall.

That’s where he wants to put his diploma.

“I’m going to hang it here, above the medals,” he said, pointing high on the wall.

‘Belittled,’ determined

When he was honorably discharged, Weiner returned to the United States and enrolled in an electrician’s program at Long Beach City College. That helped him pay the bills.

He dabbled in music. The highlight was the time he played guitar with blues legend B.B. King. Once, he played in a backing band at the Grammys. He worked as a security guard for stars such as Michael Jackson, Sting and James Brown.

Weiner has been married twice and is the father of three sons and a daughter.

A couple years ago, he heard from another veteran what a thrill it was to be awarded his high school diploma. In 2016, Weiner called Long Beach Unified, explained his situation and was denied.

They told him he would have to make up classes if he wanted to graduate.

“My attention span is not that good,” he said with a laugh.

It took him two years to work up the nerve to call again. He was inspired by talking to his friends at his 50th high school reunion.

“We talked about riding bicycles and sitting under the street light until I heard my mom whistle,” Weiner said.

He said he felt “belittled.”

“I feel like I’m less than other people,” he said.

Getting his diploma has become very important in his life.

“Ever since I didn’t graduate, I thought about it,” Weiner said. “I’m the only one in the history of my family that doesn’t have a high school diploma.”

On Oct. 22, 2018, he finally wrote an email to Long Beach Unified asking if they would grant him a diploma.

The email exchange shows that he was very upset when he was told no. And that the district was very adamant that he would not be receiving a diploma.

“At this point, I’ve given up on human decency,” Weiner wrote.

———

©2018 The Orange County Register (Santa Ana, Calif.). Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.