Editor’s note: Not long ago, the British Army approached August Cole, author of the 2015 E-ring cult thriller Ghost Fleet and former director of the Atlantic Council’s Art of the Future project, with a question: What will the operating environment look like in the 2030s?

The result is “Automated Valor,” a short story running in Proceedings, the monthly magazine published by the US Naval Institute. The story puts the reader in the command capsule of a 3-D printed Marathon HSFV as British Commonwealth Legion soldiers take on Chinese People’s Liberation Army forces in a dispute over a port in Djibouti. One element largely absent from the war theater: the United States. “I’m not saying America will retreat from the world stage,” Cole told Task & Purpose, “but I think it’s possible.”

The story is crammed with enough future-tech gadgetry to make a DoD procurement specialist swoon — from on-board AI (with a flexible leadership style tailored to each crew) to artillery-delivered bot swarms — but what gets Cole’s work onto the must-read lists of top military brass are his predictions about the context in which these wars will be fought: In “Automated Valor,” air support is purchased on the open market in real time, as are situational awareness services. Wide adoption of e-citizenship gives the British Empire a global jumpstart. Augmented reality fields are easily hacked, and the ability to maintain what Cole calls “cognitive camouflage” may be the most critical factor on the battlespace.

A former reporter for the Wall Street Journal who still writes straight analysis on occasion, Cole has found that given the speed of change, his pivot to fiction has actually made his work more influential among war planners. “You write a white paper, you don’t know how many people are going to read it,” he says, noting that his Atlantic Council colleague Max Brooks calls such documents “printed Ambien.”

“Automated Valor” is more like a jolt of Provigil, albeit with an dystopian hangover awaiting us when the excitement wears off. “The crew is living Black Mirror minute by minute,” Cole says.

Check out an excerpt of “Automated Valor” below, and read the whole story at Proceedings.-Aaron Gell

Port De Djibouti, Djibouti Free Trade Zone—April 2039

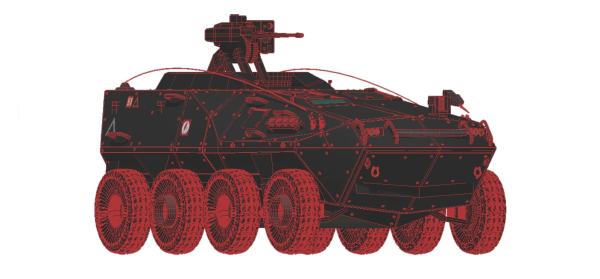

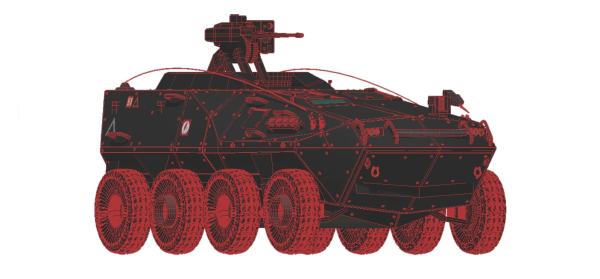

Sticky’s seat began vibrating, a resonant warning from deep inside the British Commonwealth Legion high-speed fighting vehicle, a Marathon HSFV. Then the gunner felt the closing Chinese bot swarm almost in her teeth—as if the sound were coming from her and the crew, not a fast-approaching enemy.

“Move, move, move!” she shouted. The closer the threat, the more her harness tightened, shielding her behind the combat couch’s blast-resistant wings. It felt as if somebody were hammering her coffin lid down while she was paralyzed but still alive. This particular fear was a well-worn track for the 24-year-old private. To suppress the panic, she angrily gloved a salvo of 30 thumb-sized diverters skyward. She quickly followed them with a pair of four-inch pulse-mortar rounds. Those would float gently down on parachutes, shorting out anything electronic within a five-meter radius until they exhausted their batteries. Her haptic suit pinched her to let her know it was overkill for the incoming threat, but it still felt right. She could answer for it when she wasn’t as worried about dying—whenever that day might come.

“Steady all. Shift to position Delta-6,” said Churchill— the Marathon’s commander—in a comfortingly steady voice. The eight-wheeled vehicle crabbed sideways, swaying slightly as it always did when the castering wheels moved it laterally. Down a muddy side street for a few more seconds, then a surge forward as each wheel’s electric motor spooled up.

The 28-year-old driver and mechanic, who went by “C” and was born in Krakow, Poland, had his hands calmly on the controls on either side of him, ready to take over in an instant if need be. C was the team troubleshooter. His physical bulk nearly kept him out of Marathons—he barely fit into the combat couch—but the personnel algorithms kept selecting him for deployment. Churchill and the crew were part of the British Commonwealth Legion’s Third Medium Combat Team. The 3-MCT, an all-Legion unit, was deployed to Djibouti as part of the British Army’s Second Special Purpose Brigade Combat Team.

The hull vibration eased as the artillery-delivered swarm fouled itself on Sticky’s countermeasures. She began to breathe again, looking over at JoJo, 32, a staff sergeant and the onboard integrationist, who nodded his head to a beat nobody else could hear. It was against regulation, but Churchill tolerated JoJo’s powered-up audio implants so long as they only played music stored on the bio-memory woven around his left collarbone. JoJo still liked the Venezuelan hip-hop he grew up with. His eight years in the Commonwealth Legion, testified to by the ivy-like facial tattoos that spread after each deployment, had Churchill thirstily drawing knowledge from him. It was their first deployment in this particular Marathon, 3-D printed on HMS Centurion four months ago on the calm waters of the Persian Gulf.

There was little to say at a moment like this. Talking just got in the way of communication. Everybody on board was acutely attuned to the snaps and cracks, whirs and grinding that passed for a kind of dialogue between human and machine. Their Marathon, with its high-energy laser main gun and a menagerie of small antipersonnel and antiarmor bots, was supposed to occupy a blocking position alongside a joint American and Kenyan armored force. They were four days in, trying to prevent a quasi-civilian Chinese resupply convoy from reaching the People’s Liberation Army infantry and PLA Marines occupying the port district in Djibouti City. But, as often happened, the Marathon had been rerouted mid-mission by an order conjured out of the digital ether and relayed to them by Churchill.

Then the Marathon was falling, before the hull bottomed out and bit concrete. JoJo centralized the view for the three Commonwealth Legion soldiers inside the HSFV’s command capsule: They were now two stories underground in a parking garage beneath a 15-story apartment building, dust motes swirling like snow. To squeeze into the area, the Marathon’s turret folded flat against the rear hull deck and its dynafoam tires softened, allowing the six-ton Marathon to slam its way into a concealed position beside a burned-out panel truck whose side door, spilling out wiring and looted pipes, gaped like a corpse’s mouth. Between its current position and the likely path of approaching infantry was a massive crater, at least ten meters across, caused by a driverless–car bomb of some kind.

Sticky’s right glove tickled, and she saw that she was being prompted to deploy a shield-web. She did so with the flick of her pinkie. A tennis-ball-sized container dropped off the side of the Marathon and split into three disks. They rolled in front of the vehicle before popping open and ejecting a faintly visible tangle of tacky, silvery line. The web stuck to the cracked ceiling and the detritus that covered the floor. The debris—car tires, a refrigerator door, shell casings—was proof of fighting inside the garage not long ago. Like all garages, this one made for a valuable impromptu redoubt. Back and forth the pucks rolled, weaving a nearly invisible web that would inhibit, if not stop, the approaching bots.

“Mate, can you reach Granite Two and Three?” Sticky asked JoJo.

Alex Jay Brady for Proceedings

In support of the light Marathons deployed in the port area, two regular British Army tank platoons from the King’s Royal Hussars, a heavy combat team, protected a logistics point near the airport. The Royal Hussars drove heavily evolved Challenger 3 tanks, successors to the 70-ton brutes that were the dominant armored vehicle at the start of the 21st century. In each platoon of four, one tank was conventionally crewed by just two soldiers, while three ran autonomously under low-profile turrets that looked like storks’ beaks.

“Negative on the heavies,” said Churchill. “Can’t risk comms. We get in enough trouble, they’ll get here soon enough.”

“No way,” said JoJo. “Hours away. Days even. When was the last time they made a difference, anyway? Get in the way every time. This one time in Malaysia . . .”

“Staff Sergeant,” said Churchill.

“Copy that, sir,” said JoJo.

The HSFV’s recirculation fans kicked on as vents closed to further conceal their presence. Sticky lifted her goggles and rubbed her eyes, carefully adjusting the headband-like fabric around the crown of her head. She stretched her jaw, shifting her helmet earbuds. As she did this, Churchill said, “Rollers out.” Churchill deployed half a dozen rollers, balls that functioned as both scouts and mines, inflating and deflating to scoot up, over, and around the rubble. . . .

To read the rest of “Automated Valor,” visit the Proceedings website at www.usni.org/proceedings/automatedvalor.

■ Mr. Cole is a writer and analyst whose fiction and research explores the future of conflict. He is the co-author of Ghost Fleet: A Novel of the Next World War (2015) and has written numerous short stories exploring artificial intelligence, robotics, and information operations in warfare. He also edited the Atlantic Council’s War Stories from the Future (2015) anthology. This story was commissioned by the British Army Concepts Branch to stoke dialogue and debate about force development and military operations in the 2030s. He has previously written about the future of war in the May 2016 Proceedings, and spoke on the topic at West 2018.

■ Ms. Brady is a freelance concept artist living in Cambridge, England. Her work has appeared in the game Battlefield: Hardline and the film Guardians of the Galaxy, as well as the forthcoming movies Captain Marvel and Niell Blomkamp’s Gone World, both to be released in 2019.