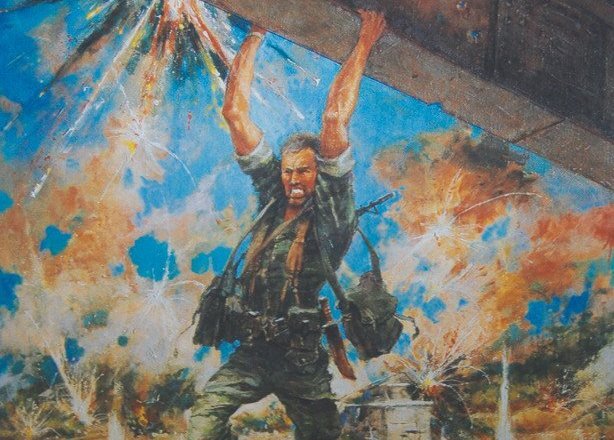

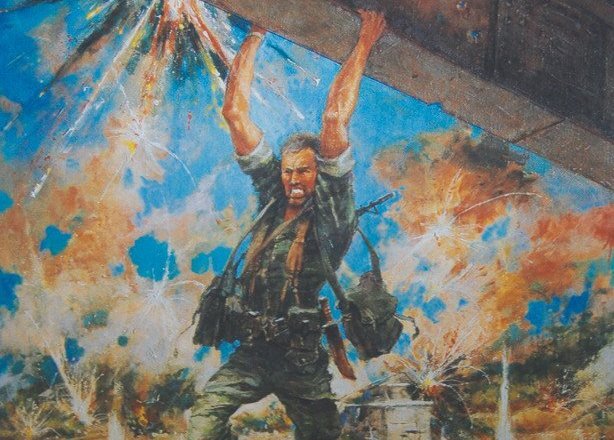

This week marks 52 years since one Marine stopped 20,000 North Vietnamese troops and 200 enemy tanks by climbing hand-over-hand beneath a major bridge to plant explosives.

In the spring of 1972, the North Vietnamese Army launched the so-called Easter Offensive, its largest attack of the war and the first major assault since the Tet Offensive four years earlier. On April 2, the communist forces reached the Dong Ha Bridge over the Cua Viet River in Quang Tri Province, South Vietnam.

Marine Capt. John Walter Ripley, the Senior Advisor to the 3rd Vietnamese Marine Battalion, was on the south side of the bridge. His orders were blunt, “Hold and die.”

Ripley, who had been wounded during his previous tour in Vietnam, saw that South Vietnamese engineers had not properly set explosives on the bridge. He knew the only chance at stopping the enemy offensive was to destroy the bridge. And he was certain that doing so would cost him his life.

“The idea that I would be able even finish the job before the enemy got me was ludicrous,” Ripley later told the U.S. Naval Institute in 2007. “When you know you’re not going to make it, a wonderful thing happens: You stop being cluttered by the feeling that you’re going to save your butt.”

Ripley cut himself severely as he climbed over a fence topped with razor wire to reach the bridge.

“I’m dangling under the bridge and hanging by my arms with a full load of explosive,” he told the U.S. Naval Institute. “I would drop down out of the steel, grabbing the flanges of the I-beam; swing sideways, and leap over to hand walk all the way out over the river.”

Subscribe to Task & Purpose today. Get the latest military news and culture in your inbox daily.

He spent more than three hours swinging hand over hand on the bridge’s I-beams to place 500 pounds of explosives, all while being shot at by enemy small arms and machine guns.

To stave off exhaustion, he constantly recited a simple prayer: “Jesus, Mary, get me there; get me there,” he later told The American Society for the Defense of Tradition, Family and Property in a 2008 interview.

But the work was so strenuous that he briefly passed out. When he regained consciousness, a North Vietnamese tank opened fire at him.

The tank round hit the bridge, ricocheted, and exploded on the riverbank, Ripley said in 2008 when he was inducted into the U. S. Army Ranger Hall of Fame.

“Boy, when that 100mm round went off with me in the steel of the bridge, what a racket,” Ripley said.

Ripley had graduated from Airborne, Scuba, Ranger, and Jumpmaster courses to serve with the 2nd Force Reconnaissance Company, according to his Marine Corps biography. He had also attended the Marine Commando Course at Lympstone, England; he campaigned with the Royal Gurkha Rifles for several months; and he completed the Joint Warfare Course at Old Sarum, England.

He needed all his special warfare training to take the bridge down.

“I learned how to place charges on opposite sides of a rail so the blast twisted a critical support,” Ripley recalled in 2008. “It would have never been successful had I not known that. I have to credit my Ranger training and also my British Royal Marine commando training.”

After Ripley placed the explosives onto the bridge, he started biting down on blasting caps to attach them to the fuses, John Girder, author of The Bridge at Dong Ha, told the New York Times in 2008.

“If he bit too low on the blasting cap, it could come loose,” Girder said. “If he bit too high, it could blow his head apart.”

Ripley connected the blasting caps to a time-fused cord and then hurried off the bridge before the explosives detonated.

He made it to safety just a few moments before a massive explosion that blew him through the air.

“I’m lying on my back, looking skyward, and I can see enormous chunks of this bridge going through the air,” Ripley told the U.S. Naval Institute. “It was a tremendous feeling.”

By destroying the bridge, Ripley created a logjam of North Vietnamese tanks that U.S. bombers and warships were able to hammer. The Easter Offensive failed and Võ Nguyên Giáp, who had led the Vietnamese communists to victory over the French decades earlier, was replaced as the commander of North Vietnamese armed forces.

Ripley was awarded the Navy Cross for his bravery at the Dong Ha Bridge. His award citation credits him with “saving an untold number of lives.”

He retired as a colonel in 1992 and died in October 2008. He is buried at the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, which has immortalized his bravery with the realistic diorama “Ripley at the Bridge” in Memorial Hall.

Roughly a month after he destroyed the Dong Ha Bridge, Ripley received a “bill” for the damage he caused. The letter, which was meant to appear as if it came from the North Vietnamese government, was sent to Ripley’s commanding officer and the officer in charge of the Ranger School at Fort Benning, Georgia.

Ripley was told he owed 40 million Piasters to repair the bridge.

“Also, on behalf of General GIAP, it is requested that you depart Quang Tri Province immediately and do not ever, repeat ever, return,” the letter read.

The latest on Task & Purpose

- Air Force special operators must take class before getting shaving waivers

- Camp Pendleton Marines encouraged to fix their own barracks rooms

- 101st Airborne soldiers are first to receive new Next Gen Squad Weapon

- Air Force fires commander of Holloman maintenance group

- Army investigating Nazi imagery on Special Forces patch posted online