Above a stack of voting assistance pamphlets near my office at battalion headquarters, there’s a poster of George Washington with a quote of his from 1775: “When we took up the Soldier, we did not lay aside the citizen.” The message from my voting assistance officer is clear: The father of my country wants me to do my civic duty and vote.

Of course, there’s more to it than that: In his speech, Washington was reassuring nervous legislators that after hostilities with America’s British occupiers ceased, he and his officers would return to civilian life, allowing democratic processes institutions to govern the new republic, rather than military-backed authorities. The poster contains the seeds of an unresolved paradox for military personnel: We are citizens with a responsibility to engage in the national political process, yet we must moderate our engagement to avoid marrying military power with a political party.

New controversies, old guidelines

A recent blip on the news radar illustrates how knotty this paradox is — though if you blinked, you might have missed it. Maj. Gen. Ryan Gonsalves’ promotion to lieutenant general was reportedly withdrawn last November after an Army inspector general’s investigation found Gonsalves had made chauvinistic and partisan remarks to a female congressional staffer in 2016. A “preponderance of the evidence” showed Gonsalves disrespected the staffer by calling her “sweetheart,” asking her about her age, and chiding her to take good notes during their meeting “since she was a Democrat and did not believe in funding the military.” (You can read more details from the report here.)

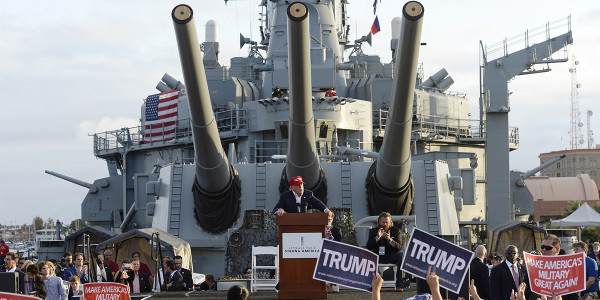

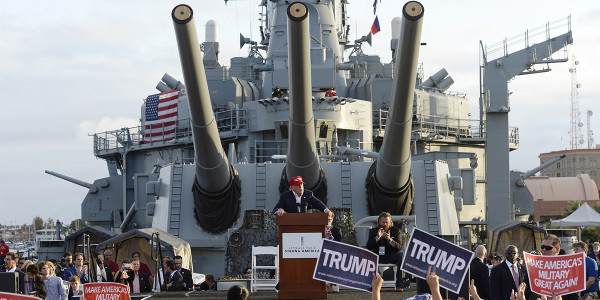

The Army this month declared the case closed, with Gonsalves receiving “administrative action” for his undignified remarks. But he wasn’t punished for the partisan nature of his remarks, and that raises questions about an erosion of non-partisan norms in the U.S. officer corps. From General McChrystal’s career-killing Rolling Stone interview to the star-spangled Republican and Democratic conventions of 2016, recent political history contains an unsettling amount of military misadventure. After the domestic tumult of 2017, political expression among military leaders needs to be re-surveyed. Where must civic engagement yield to military professionalism? What is acceptable political expression? The answers are important, because they undergird the massive public trust the military currently enjoys.

The Uniform Code of Military Justice and DoDD 1344.10 set out our limits of political expression. Members of the military may not make “contemptuous” statements about the president, Congress, and a number of other elected or appointed officials in public. We may not engage in partisan activities or imply their endorsement by the Department of Defense. But recently retired service members, particularly flag officers, are a different case. They have an outsize influence on the public discourse, based on the rank they once held, and so their political behavior has been moderated primarily through societal norms rather than prosecutions. And those norms seem to be shifting in recent years.

The decay of servant leadership

Junior officers and enlisted personnel take their cues from more senior service members, and when strong opinions are expressed in front of soldiers, they leave a mark. They can affect morale and undermine faith in our political process. I don’t anticipate a breakdown in the tradition of military obedience to civilian authority any time soon, but I am pessimistic about its long-term health. The erosion of these norms begins innocuously, unfolds slowly, and hardly attracts our attention. The military doesn’t suddenly break into the open as a political actor, but becomes one after the decay of servant leadership, as lapses in discipline become more common and societal pressures become less strict.

Flagrant political overtures are simple enough to spot and hold in check. But the terrain grows far more hazardous as those of us on active duty grow more vocal. Over the years, changes in military policies have generated institutional resistance, but usually stopped short of overt partisanship. Desegregation once had its vocal opponents in the military, as did permitting women in in ground combat, on submarines, and in fighter jets, along with allowing openly gay and transgender service members. These aren’t the only high-profile political fights that have roiled the military: In 2007, a group of 1,700 junior servicemembers made an “Appeal for Redress,” demanding that Congress withdraw U.S. troops from Iraq. And, of course, West Point graduate 2nd Lt. Spenser Rapone stirred controversy with his “communism will win” message and Che Guevara undershirt photo, posted after he’d graduated in May 2017.

Why now?

But recently, there is a palpable change in the political ecosphere. Why does the present moment seem different? Why does it seem harder than in the past to keep our politics to ourselves in the military? I suggest that there are two trends at play here.

First, we are just as affected as the rest of the U.S. population by a deepening national rift. By many measures, the country is more deeply divided over socio-political issues than it has been since the civil rights movement. Nearly every difference of opinion seems cast in the language of good versus evil, and so we are more compelled to speak out for what each of us believes is the good. A recent Military Times poll showed sharp differences among military personnel over their private views on the current administration — and those views differed substantially from the rest of the country.

Second, we have developed an unhealthy separateness from the civilian world that manifests as self-righteousness. T&P;’s Tom Ricks documented that trend in a 1997 Atlantic article, and it seems only more firmly entrenched 20 years later. Somewhere along the way, the officer corps’ self-image of aloof guardianship has grown caustic and damaging. Andrew Exum, a former infantry officer who served as a deputy secretary of defense, recently wrote that “ you keep treating the U.S. military like a privileged class—a class of men and women above the citizens it swore to defend—it will start acting like it.”

Wholesale moral/political division and military elitism: We stand at the confluence of these two trends, and phrases like “you are a Democrat and do not believe in funding the military” carry hints of both.

Being honest brokers

So much of what we value in our country exists primarily in the abstract, but feels real nonetheless. An apolitical military service isn’t something you can wrap your arms around, but nearly all of us believe in its importance… even if we unintentionally undermine it at times. Simultaneously, America’s longstanding vision of authentic citizenship calls for us to engage with our democracy and its political processes. No easy chart exists to help us plot a course between civic engagement and dangerous politicking. The UCMJ and our usual norms only carry us so far; we are left to our own best judgment to negotiate the gray areas.

When in doubt, the spirit of the U.S. commissioning oath establishes the moral basis for our actions as officers and fixes our loyalty to the Constitution, rather than a person or party. Our political neutrality makes us honest brokers. Even if some Americans were to cheer us when we march onto the stage and support their candidate, another segment of the population, made up of equal citizens, is left to wonder if the military acts as defenders of right, or a mere opposition party. The American public in near-entirety — liberal, conservative, centrist — trusts us because they believe we will execute the will of whomever they elect. To throw our support behind one party or another is, in effect, an abuse of the trust the country has invested in us. If we persist in the abuse of that trust, the country will rightfully learn to despise us.

Wesley Moerbe is a veteran of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars and remains on active duty. He has served at the division, brigade, battalion, and company echelon. His work has also appeared in Military Review, Infantry Magazine, and Collateral Journal. The views expressed are his own and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.