There are a lot of jobs in the Marine Corps. And one, improbably enough, is capturing the work that Marines do through illustrations. Yes, for all the jokes about crayon eating, there’s at least one Marine who puts those pens and pencils to paper, and produces some amazing work while he’s at it.

“The purpose of the [Marine Corps Combat Art Program] is to document Marine Corps operations via illustration for historical documentation,” said Capt. Charles J. Baumann, a logistics officer who joined the program in 2015. “I hope to contribute to the collections of work archived in the [National Museum of the Marine Corps] and provide a slightly different perspective to viewing the recorded history of the Marine Corps. I hope that in 10, 20, 50 years my artwork can be used to help tell the story of the Corps while I was in service.”

In June, Baumann was sketching a Marine Raider unit at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina prepping for a training exercise, along with Capt. Michael Reynolds, who is another applicant to the program. The field is a small one in the Marine Corps. Baumann is the only active-duty Marine along with a handful of civilians who participate in the program. Another Marine, Staff Sgt. Elize McElvey, left active-duty in 2020.

As the lone active-duty combat artist, it’s on Baumann to coordinate when and where he goes to draw, and as an additional MOS, it comes second to his duties as a logistics officer. Still, since joining the program in 2015, Baumann has embedded as a combat artist on deployments to Iraq, Africa and Norway producing artwork that is available to the National Museum of the Marine Corps and whichever units are profiled.

While some units might be skeptical at first — when was the last time you had an illustrator in camp? — as Baumann said, “once they see what we can do, they get excited and almost 100% of the time they enjoy having us around and invite us to unique opportunities, which feeds right into what we try to do.”

In an era of ubiquitous cellphone cameras, it may be hard to imagine that there’s still a program to draw what Marines are doing, but combat artistry has quite a long history.

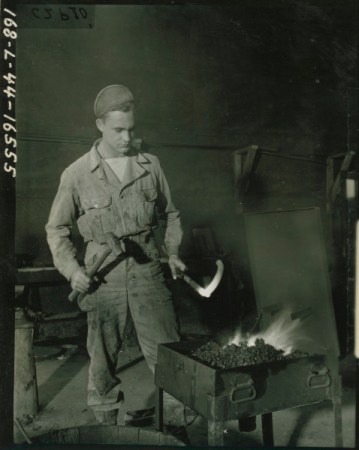

Starting in World War I, the U.S. Army was dispatching artists to the front lines to record what was happening. That continued on into the Second World War when dozens of artists, some of them civilians and some of them serving in uniform, were sent around the world to document the war. One of them, Thomas Lea, was already an accomplished artist when the war began, painting for Life magazine and the Works Progress Administration. During the war, Lea was sent to the Pacific to document the fighting in places like Guadalcanal and Peleliu. His sketches captured all aspects of combat. From the moments before battle, like a Marine standing in a landing craft waiting to go ashore, to a bloodied Marine wading across a beachhead, to casualties being treated or a single Marine giving the “2,000 yard stare.”

The program, along with similar combat art programs in the other branches, has intermittently continued since then.

“The active duty MOS was decommissioned in the early 2000s and the program was absorbed by the National Museum of the Marine Corps, but because it wasn’t really advertised there were long gaps where there just wasn’t anyone with that additional MOS,” said Baumann.

The most important skill for a combat artist these days is being able to accurately capture the lives of Marines around the world.

“It’s someone’s impression. A photograph is a slice of time, an instant. I think art can span time with an impression of an idea rather than a slice of time,” Jim Butcher, a Marine Corps combat artist who served during the Vietnam era, told the National Archives in 2018.

The current Marine Corps Combat Art program is open to any military occupational specialty, as long as you’ve got some aptitude for artistry. So if you’ve got the pencil chops, you can apply.

As the saying goes, “a picture paints a thousand words.” Which is kind of the point of the program.

As Reynolds, the aspiring combat artist said, “I recall the smell of JP8, the feel of moondust beneath my boots, and the sounds of the rumbling engine of the Humvee in the distance. It’s that level of connection that I am to achieve in hopes that someday, someone can recall and connect with what I’ve illustrated to tell a story using non-verbal communication.”

The latest on Task & Purpose

- Navy Blue Angels had to change their show after jet caused $180,000 in building damage

- The Army is getting leaders ready for a war unlike any the US has ever seen

- We salute this Marine for having a promotion ceremony in the muck

- Navy fires nuclear submarine captain after only 8 months on the job

- A Navy warship burned while commanders argued over who was in charge

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.