Ten years after leaving Iraq, the hardwired lessons of war still manage to sneak up on me. The lingering effects of PTSD became clear to me in 2015. I was on a northbound train from New Delhi to the India-Pakistan border, when a chocolate vendor hopped on board our crowded 54-bunk sleeper car. The man across from me declined politely. Then he leaned toward me. I should never buy from the vendors, he said, because sometimes they inject drugs into the food.

“Good drugs?” I asked with a smile. I was trying to think of a scenario where it would benefit a poor ruffian to get a stranger stoned.

“No, no,” He laughed. “Bad drugs.”

His name was Sunil, and he was a doctor working for a non-profit that served residents of the slums in suburban Punjab. He recalled once treating a patient who boarded a train to the North and never made it. The patient was found three days later, naked and partially blind with memory loss.

I’d experienced worse. I bought a bar of chocolate and took a bite, hoping it would quell the growing unease I’d been feeling in my stomach since shortly after my arrival in India. The lavatories on a second-class Indian train car are nothing to trifle with, and I didn’t want to face one on my knees. I thought of that old Imodium slogan: Where will you be when diarrhea hits?

Dr. Sunil looked like the kind of doctor you trust. Middle-aged with comfy shoes. Plaid shirt tucked into his trousers. Phone and pens in his breast pocket. I gave a final chomp to the chocolate bar and offered him the remainder. He accepted as a matter of social protocol, “bad drugs” or no.

As darkness fell, I settled into the bunk. Before long, the train pulled into a station and stopped. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw the good doctor disembark, off to use the station bathroom, no doubt.

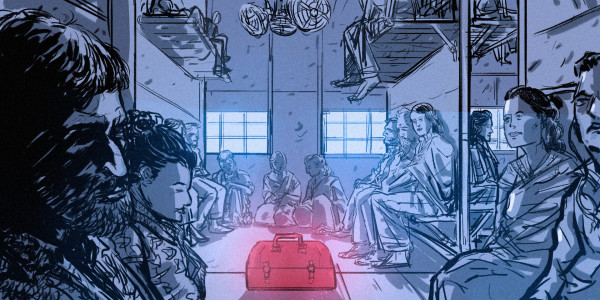

I knew he’d be coming back because he’d left behind his briefcase, a ballsy move. In keeping with the unspoken agreement between travelers, I watched over it as passengers squeezed through the corridors, crowded with tea vendors and begging children. Before long I started to worry he might not make it back in time. A few minutes later, I found myself inventing excuses for his extended leave. That’s when the anxiety started creeping in. My breaths grew shallow, and my blood cold. Something was very wrong.

It wasn’t fear. It was something else. That tension in a horror film. The uneasy feeling that grows with each step the protagonist takes deeper into the woods. Something bad was going to happen.

Why the hell would he leave his bag?

A night train in Punjab.Ben Feibleman

I realized I’d been eyeballing it for a full minute, burning up the briefcase with my thousand-yard-stare. I was no longer concerned with thieves, much less chocolate sellers. Now all I could think about was how odd that was, really, leaving a bag all alone on a crowded train.

“If you see something, say something.” That’s what all the security posters say in New York, right?

I told myself I was just being paranoid and took a slow, deep breath to regain control.

This was post-traumatic stress disorder. The memory of every explosion I heard in Iraq. Of every rotting corpse I saw in Liberia. I may have been concentrating on the briefcase, but those memories were calling to me, just beneath the surface.

Nevertheless I kept staring. I was in a crowded train car, but alone. Me and the bag. Just the two of us and a bright flashing sign that said “DANGER!”

With my breath still, the only thing I could hear was my steadily increasing heartbeat accompanied by the single-string whine of my tinnitus. A horrorshow soundtrack of my own biology.

If you see something, say something.

A few years ago, I had a little dispute with the New York Police Department over the appropriate locations in which to park my motorcycle. One day, as I waited at the impound lot to ransom back my bike, a man walked in with a bag over his shoulder and after a few minutes in line, placed it on the ground and left. Probably to the bathroom, right?

This was after the Boston Marathon bombing, and everyone was on high alert. It didn’t take long before someone asked whom it belonged to. “Excuse me, Sir, is that your bag? No? … Ma’am, is this your bag?” The lonely bag grew more sinister with every inquiry, and the polite questions became an interrogation. Soon, the people crowding the impound office were on the verge of panic. I was uneasy, too, but we live in Freak-Out Nation, and, this being America, I figured the odds were that the owner was stupid rather than evil. So I walked up to the bag and unzipped it to settle the matter. As my fellow citizens suspended their hysteria for the moment, I riffled through bag’s insides … And guess what? No bomb. Everyone let out a breath, and I took my seat, leaving the solitary bag to await its owner and his public shaming.

Now, on the train, the briefcase belonging to one “Dr. Sunil” sat just as lonely. But this wasn’t America. Now I was the one feeling panicked.

Whole minutes had gone by. I was still frozen, staring as the train rocked under the weight of passengers. How is he not back on board, yet? At last I broke away and bolted towards the door to see what was happening outside, hoping to see Dr. Sunil’s plaid shirt and smiling face. Instead, I saw trees whipping by, power lines bowing up and down.

Wait, we’re moving? As it dawned on me that the train had actually left the station, panic won out over reason.

Maybe I’m wrong, I thought. Maybe he’s just in the bathroom.

No, I saw him get off. I know I did.

I kept thinking of something my friend Jason told me once.

We were walking through Kabul, dressed in tribal costume, not a kilometer from where a car bomb had gone off the day before. Jason had worked with a lot of explosives in the Marines, and he explained that during a bomb blast, there’s heat and shrapnel, both of which can kill you, but just as bad is the air pressure. Diving into a ditch like an action hero before it goes off might save you from the first two but not the third. In fact, it will only prolong your suffering. The air pressure causes your lungs to expand like you just inhaled an entire hot air balloon.

A typical bomb is a little like one of those big, round fireworks. It explodes in every direction. But when it’s laid on the ground, that downward force gets redirected outward, and as each side is closed off, the force grows exponentially. A grenade rolled against a curb is four times as destructive as one that explodes in mid-air. In a second class sleeper car with sealed windows, a bomb of any size would be devastating.

As I caught myself trying to work through the physics I shook my head and again told myself I was just being paranoid. But fear is an instinct, not a rational thought. I forced myself to stare at the ceiling and hold my breath to slow my heart rate … the adult version of a child pulling the covers over his head.

Would it be awkward if he caught me digging through his bag? See something, say something, right?

At last I sat up, mustering the courage to inspect the bag, to settle the matter just like at the tow pound, and right as I swung my legs off the bunk, Dr. Sunil appeared before me.

Oh. It wasn’t him I’d seen exit the train after all. It was some other plaid shirt.

The bathroom.Ben Feibleman

He took his seat and resumed reading his newspaper, oblivious to my terror or my pounding heart, now pumping so hard it would break an EKG. And though I was relieved, the revelation brought no relief to my symptoms. The train conductor shut off the lights, and between the sound of the rails below us and the occasional squeaking wheel, soon everyone was rocked to sleep.

Everyone but me. A hundred miles later you could still find me sitting there. I could have laid down and closed my eyes, but I’d still see the bag. Still feel its threatening presence.

That fear, born far behind us on the tracks, would never obey reason. It would obey chemistry, however, and I, like so many veterans, had my options. Ambien, Ativan, Xanax. Benzodiazepines and SSRIs. Say the right words to any VA doc and life becomes a real buffet of pharmaceuticals. From the bottom of my bag I fished a little white pill the size and shape of a baby aspirin and tossed it into my mouth, letting its chalky texture dissolve under my tongue.

I don’t mention the drugs to glamorize them. Like most people, I’d prefer to calm or soothe these episodes with natural remedies like breathing exercises or meditation or thinking happy thoughts, but that was easier said than done. I was 10,000 miles from home with two black eyes and a heart on the verge of attack. And since no one was kind enough to slip tranquilizers into my chocolate, I’d just have to do it myself.