This year alone, the U.S. government designated 19 groups as terrorists, a massive spike compared to the last decade. Several are criminal organizations allegedly involved in trafficking drugs.

Of those designated as Foreign Terrorist Organizations by the State Department this year, eight are drug cartels, such as Cártel de Sinaloa, Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación, Cártel del Noreste, La Nueva Familia Michoacana, Cartel del Golfo, Carteles Unidos, Tren de Aragua, and Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13).

Most recently, Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced that the U.S. plans to designate a twentieth foreign terrorist organization on Nov. 24, yet another drug cartel: Cártel de los Soles.

President Donald Trump’s administration has accused Venezuelan strongman Nicolas Maduro of leading Cártel de los Soles, describing it as a major criminal organization that seeks to “flood” the United States with illegal narcotics.

“President Trump is using every possible measure to bolster US national security and protect our homeland against foreign terrorists seeking to harm Americans,” White House spokesperson Anna Kelly told Task & Purpose. “These terror designations enhance the administration’s ability to support law enforcement and rob these groups’ ability to seek financial and other support.”

In contrast, the State Department designated a total of 18 groups as foreign terrorist groups in the decade prior to the start of Trump’s second term. The next highest number of designations took place in 2018, when six groups were added to the list. No new groups were designated terrorist organizations between December 2021 and Trump’s return to office.

Based on interviews with Latin America and military experts, the sharp rise in designations could indicate that the Trump administration increasingly views narcotics traffickers as a problem that requires a military solution. And that could open the door for wider military action in Venezuela and elsewhere in Latin America.

‘No different than al-Qaida’

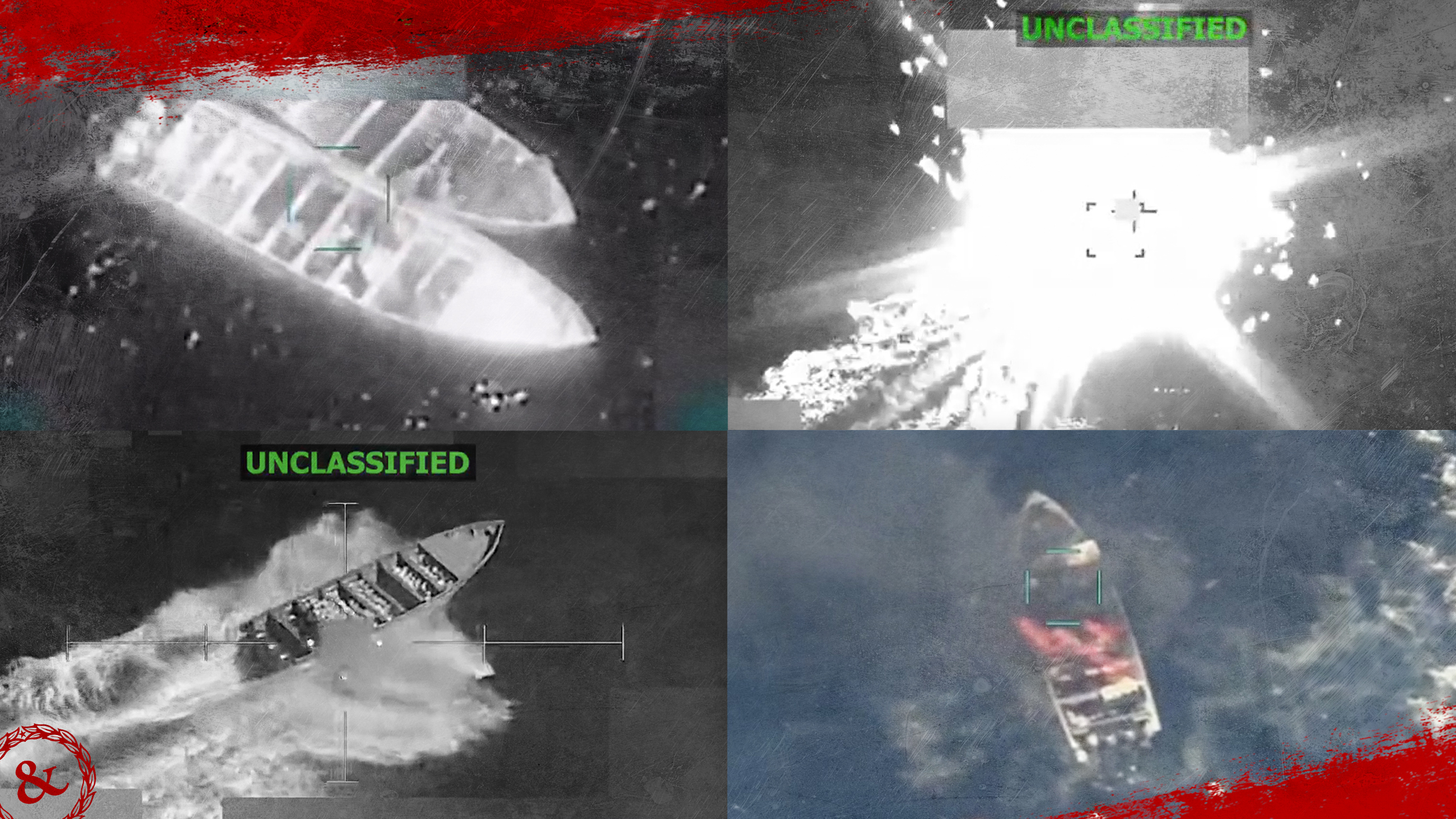

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth has cited the designations of cartels as terrorists to defend ongoing strikes against suspected drug operations in the Caribbean and Pacific, routinely referring to those manning the fishing boats as “narco-terrorists.”

“A foreign terrorist organization poisoning your people with drugs coming from a drug cartel is no different than al-Qaida — and they’ll be treated as such, as they were in international waters,” Hegseth said in September while visiting Fort Benning, Georgia.

Officially categorizing groups as foreign terrorist organizations doesn’t “magically” authorize the use of military force, which is the job of Congress, said Brian Finucane, a former State Department lawyer who advised on counterterrorism operations and current senior adviser for the International Crisis Group. However, the Trump administration has unilaterally decided to strike targets without approval from federal lawmakers, he added.

Rather, the designation authorizes visa restrictions for group members and associates and makes it a crime to knowingly provide support to those organizations with money, weapons and training, a senior administration official said.

Top Stories This Week

“But politically, this administration has used these designations to pave the way for military action,” said Finucane, who noted that the State Department designated the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, IRGC, as a foreign terrorist organization in 2020, which preceded the drone strike that killed its commander, Qasem Soleimani.

Finucane said that other colleagues of his at the International Crisis Group have even questioned whether Cártel de los Soles officially exists and if Maduro is at the helm.

“The administration has referred to not just the people on these boats as blowing up in the Pacific and the Caribbean as narco-terrorists, it’s also referred to Maduro himself,” Finucane said. “This is a further potential stepping stone to military action and an attempt by the administration to delegitimize him.”

Meet the new war. Same as the old war.

Since 2001, the majority of U.S. designations have been related to Global War on Terror operations and included nearly three dozen Islamic extremist groups. Those have ranged from more-established groups in the Middle East like al Qaida and the Islamic State, to offshoots like Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISIS-K) and others operating in parts of Africa like al-Shabaab and Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin, or JNIM.

Then in February, the State Department designated eight drug cartels as terrorist organizations with plans for a ninth group announced by Rubio.

Jose Enrique Arrioja, senior director of policy at Americas Society/Council of the Americas, said the designated groups are all criminal organizations using gangs for “expanding, organized, illegal activities — not only in drug trafficking but extortion, kidnapping as an industry.”

In 1997, the U.S. designated the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN) in Colombia as foreign terrorists, but those groups were “more proactively engaged in a political change in Colombia,” Arrioja said.

The modus operandi of the latest drug cartels cited by the U.S. is more about wielding power over local politicians in Latin American cities or states — most of the time through extortion, he said.

“[The cartel groups] just simply control it and make sure that whatever policies come from that specific office will play [to] their benefit, will allow them to continue moving in the shadows, will allow them to continue operating without disruption,” Arrioja said. “They want to coexist with whatever the political regime, left or right or center, is in power.”

In general, drug cartels are better classified as criminal organizations rather than terrorist groups, a retired senior military U.S. commander told Task & Purpose. The Coast Guard and Navy have long partnered in a law enforcement effort to stop boats carrying drugs, which are often crewed by a few smugglers who are “the lowest of the low in terms of the criminals,” the retired commander said.

The move to label criminally backed or gang-affiliated organizations as foreign terrorists is completely new, according to Finucane.

A major difference, Finucane said, is the fact that “there has been no 9/11” where thousands of Americans were killed in a direct attack by “organized armed groups capable of being in armed conflict with the United States.”

“Tren de Aragua is not an organized armed group in the way that al-Qaida or ISIS was,” he said. “[Drug cartels are] trying to sell Americans an illegal product, but they’re not targeting Americans with violence. They’re not crashing airplanes into buildings and therefore using the tools of counterterrorism are completely inappropriate.”

However, U.S. military forces have been used for counternarcotics missions in the Western Hemisphere before, experts from The Soufan Center, a non-partisan nonprofit focused on security, wrote in an online analysis. Previously, this has included special operations units assisting Colombia and Mexico in counter-cartel operations and Marines partnering with Guatemala to combat the Zetas cartel.

“Approaching the cartels as a military threat increases the chances of achieving battlefield effects like destroying drug labs, sinking boats, shooting down aircraft, and killing cartel members. These operations will undoubtedly hurt the cartels,” the nonprofit wrote.

The Soufan experts also said that counternarcotics operations, similar to counterinsurgency, would require “high levels of commitment” from the host nation as a partner in combating the systematic issue to avoid “dangerous” second and third order effects.

Finucane has joined a host of other legal experts who say that there has been little to no legal justification given by the administration for the Pentagon’s ongoing maritime strikes, which now total more than a dozen. Media reports indicate that some service members have even raised concerns about the lack of a legal framework for the strikes.

“Obviously, drug overdoses, drug abuse in this country is a terrible problem, but it’s a public health problem. It’s not a military problem,” Finucane said. “It makes no more sense to try to bomb our way to victory in the war on drugs than try to defeat cardiovascular disease by drone striking McDonalds.”