Editor’s Note: This is an opinion column. The thoughts expressed are those of the author.

That Americans are hungry for leadership at the national level is an understatement. A patchwork of ideology-infused buck-passing, magical thinking, and good old fashioned incompetence at the top has done little more than deepen the partisan trenches. The country wants a plan, not just action. It’s only natural that in our current leadership vacuum, Americans turn to history for a figure to pine for, someone with a take-no-prisoners attitude, who would swashbuckle through the partisanship and rally the country to defeat COVID-19.

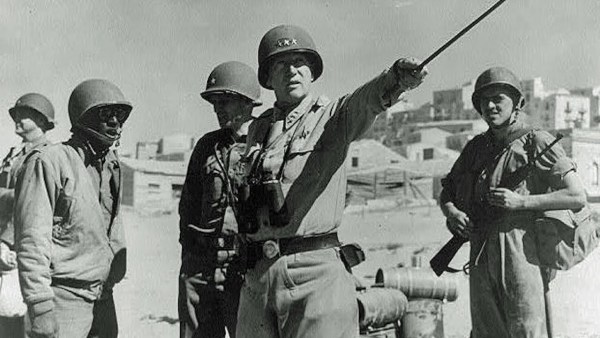

Frequently, the first and only stop on this nostalgic train ride back in time is the general staff of the US Army in World War II. Patton. MacArthur. LeMay. The showboaters with larger than life personalities, whose biographies line the shelves of bookstores and personal libraries by the million. Their practiced icy stares peer at us from dust jackets and blurry old footage in our current moment and stir a longing within certain people for leadership defined by cigar chomping and staged news footage.

Stop. The challenge posed by COVID-19 is indeed on par with the Second World War, but we’re looking in the wrong places for examples of leadership in times of great crisis, both within the generation of officers that won the Second World War and in other eras in American history. Our times call for us to stop relying upon our history’s greatest hits, the same old battle-weary warriors who are only good anymore for a quick fix of patriotic nostalgia: The most underrated part of leadership is good management.

Combat is only one part of fighting a war. Patton and MacArthur are properly included in the pantheon of great American captains, but the generals who won the Second World War weren’t “warriors,” but superior managers. George Marshall, appointed Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army at the war’s outbreak, first had to convince President Franklin Roosevelt that the Army was too small and a draft would be necessary to rapidly increase its size. Marshall maneuvered in the face of isolationists in Congress and a skeptical public to institute the draft and increase defense spending and arms production. Once the U.S. entered the war, Marshall quarterbacked policymaking for a war effort that spanned the globe and subsumed the American economy.

Similarly, Dwight D. Eisenhower never commanded a unit larger than a battalion and never fired his weapon in anger, yet he excelled as Supreme Allied Commander due to his ability to judge the political needs of the Alliance’s principals and manage the competitive relationships between American and British field commanders. And then there’s General Omar Bradley, cognizant of the Alliance’s political considerations in his operational debates with Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery yet also respectful when these conditions meant he didn’t get his way. Marshall, Eisenhower, and Bradley all understood that what they were fighting for was bigger than themselves. The future of the Army, as well as the country, was at stake. Securing victory was critical for ensuring that their successors had the best shot at building upon their efforts. Establishing something that would outlive them was stuff of true glory.

Focusing on history’s general officers also assumes that the US military has the market cornered on public service. It doesn’t. We can look no further for leadership at the civilian level than the medical profession at the dawn of the 20th century, when the “Big Four” physicians who founded Johns Hopkins University — William Henry Welch, William Stewart Halsted, William Osler, and Howard Kelly —not only pioneered medical research but transformed the practice of medicine in the United States by overhauling it’s antiquated 19th century system of medical schools. Welch forced the latest European advances in chemistry and laboratory sciences on reluctant US doctors; Halsted institutionalized operating on patients in sterile environments; Osler placed an emphasis upon his idea of doctors as researchers as well as practitioners; and Kelly pioneered radiation therapy. The idea was to change the practice of medicine in the United States by building Johns Hopkins University into the standard by which all medical schools in America would be judged. In doing so, each man led the resulting seismic shift in the medical profession through the care and dedication they showed to their students, who built upon what they learned from these giants.

The thread that binds these men together is the element of leadership Americans are craving in our current crisis: their ability to manage their particular institution. A basic concept, yes, but critical. Whether it was Eisenhower managing the latest battlefield dustup between Monty and Bradley or William Henry Welch hammering germ theory into his medical students, the most effective managers in U.S. history recognize the institution is bigger than any man. Real progress comes through the invisible tinkering that to everyone on the outside appears to happen organically.

The kind of leaders we need in our current moment wear the institution they lead about their shoulders and become one with it, rather than try to dominate it outright. Management may not be ivory handled pistol sexy, but under the right circumstances and with the right personality, good management feeds into good leadership. Pray that there may yet still be a Marshall or a Welch out there today.