PALM BEACH GARDENS — David Adan stared at rows of lights and dials for three days.

In that tense week 50 years ago, space workers on the ground were dealing with three guys who were lost in space. And even if nothing else failed, the chances of getting the three home were iffy.

But a million things could fail. And if one did, a dial or gauge at Adan’s console at Kennedy Space Center would show it.

“We sweated it out,” Adan recalled. “One thing goes wrong…”

But the three did get home.

Of all the accomplishments that Adan, now 83 and retired to Palm Beach Gardens, is most proud of in his many years in the space industry, three stand out: Being a Hispanic pioneer; helping design the lunar module that got Apollo 11 to the moon, and being a player in the rescue mission of Apollo13 in which that same lunar module had to become something it wasn’t designed to be.

“We never thought about it. That it could be a lifeboat,” Adan told The Palm Beach Post in January. “I worked on that baby day and night. And it paid off. It saved those guys.”

The Apollo 13 mission, April 11-17, 1970, was described as a “successful failure.” In its own way, it nearly was as much an accomplishment as that first moon landing just months earlier.

It sparked an award-winning 1995 movie starring Tom Hanks, so riveting that some test audiences, not realizing it was based on an actual event, said it was too unrealistic. That in real life, the astronauts never would have gotten home alive.

“We were under stress, let me tell you,” Adan said.

“There’s no room for being panicky,” he recalled. Panic would get those men killed. Instead, “We said, ‘We’ll get those guys back.'”

Slide rules and sextants

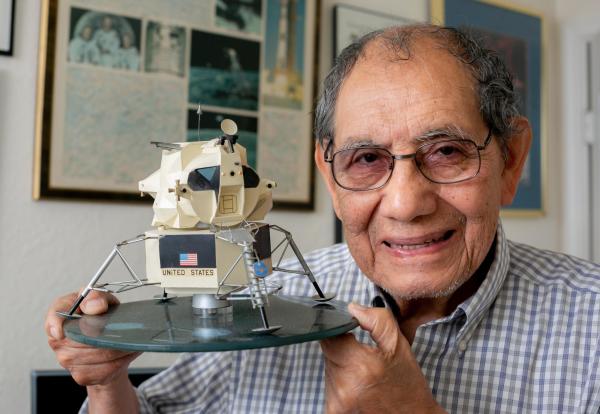

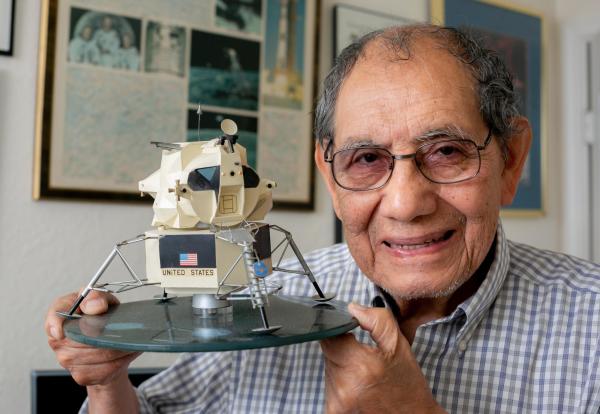

Adan’s apartment features scale models of military jets, space shuttles, and moonshot-era Saturn V rockets.

And, in a corner, on its own tray, a lunar module. It’s one of numerous scale models Grumman gave to workers who toiled on the spacecraft.The LEM — or lunar excursion module — had about a dozen systems, each requiring monitoring.

But NASA essentially was using the technology of the 1950s. Workers used the now-obsolete slide rule to do their calculations and even employed sextants, the devices mariners employed going back to when America was a bunch of colonies.

The workers included Adan. He was responsible for testing the backup for the system that would land the LEM on the moon. On the LEM, he said, “I knew every switch. Every circuit breaker.”

Adan had left Mexico City in 1952 to study in the New York area. After high school, he had wanted to be a U.S. Navy pilot. But he was color blind and couldn’t discern between red and green cockpit lights. By the 1960s, he was a technical engineer at Grumman’s Long Island plant, helping coordinating the machine’s backup guidance and navigational systems for Apollo missions. Specifically, the lunar module.

Adan told The Post he never felt scrutiny for his ethnicity. But, he said, he knew he was a pioneer. And that, like another trailblazer, baseball’s Jackie Robinson, Adan was in a fish bowl, and he didn’t have the luxury of being mediocre at his job.

“When I was a kid,” he said, “my grandmother said. ‘David, whatever you are going to do you’ve got to be the best.'”

The LEM was designed to ride aboard the Apollo spacecraft, separate in lunar orbit and ferry two astronauts to the surface. Then the top part would blast off, using the lower part as a launch pad, and would rendezvous back with the spacecraft.

The two astronauts would transfer and the LEM would fall back to crash on the moon.The machine had hundreds of parts, all with backups upon backups. But the LEMs on Apollo 11 and Apollo 12 performed nearly flawlessly. There was no reason to believe the LEM on the third moon mission wouldn’t do the same.

It never got the chance. Instead, it did something else.

“Houston, we’ve had a problem.”

At Kennedy Space Center, Adan, sitting at the Grumman console, was not in the middle of things. The second a spacecraft clears the gantry, it comes under control of Johnson Space Center near Houston. But that doesn’t mean people did nothing in Florida.

On the evening of April 13, Odyssey, the name for the paired command module and service module, and Aquarius, the LEM, already had been in space for 56 hours, more than two days.

Adan and others already were doing some work on the next mission. The crew — lunar module pilot Fred W. Haise Jr., command module pilot John L. Swigert Jr., and mission commander James A. Lovell Jr. — had just finished a lengthy TV broadcast.

Then came a sharp bang, a vibration and the illumination of a warning light. And Swigert then uttered one of the most famous phrases in space flight history, crackling through the ether:”Houston, we’ve had a problem here,” he said.

Two of the three fuel cells were fatally damaged. It didn’t take long to conclude the crew didn’t have enough fuel to get to the moon.”The knot tightened in my stomach, and all regrets about not landing on the Moon vanished,” James Lovell later wrote. “Now it was strictly a case of survival.”

Initial disappointment had morphed into grave concern. The crew might not be able to get home. Of the oxygen tanks that were feeding the surviving fuel cell, one showed empty, and the other was losing volume at an unnerving pace.

It was only days later, as Apollo 13 neared earth reentry and the command module separated from the service module, that the astronauts would be able to see the scope of the catastrophe. An explosion had ripped away much of the service module’s skin and damaged much of its insides. The blast had ruptured oxygen tank two and damaged the valve on tank one.

In three hours after the blast, the service module would have no water. No electricity. And no propulsion. It would be a dead hulk. The command module, the teardrop-shaped capsule at the tip, wasn’t a long-term option. It worked almost exclusively as part of the service module configuration, except in those last moments when it separated and reentered the earth’s atmosphere.

That left a solution that hadn’t come up in contingencies. The only one that would save the three men.

A lifeboat in space

The astronauts’ time in the lunar module, down to the moon’s surface and back, was designed for 45 hours, and that’s all the life-support crews had built in. But now the LEM would have to be a lifeboat. And for twice as long. People scrambled to improvise.

“We just stopped everything,” Adan said. “We had so many anomalies that we spent nights, days trying to figure them out.”

For the next few days, Adan kept watch on all the gauges, snatching just a few hours of sleep a night. Mission control decided the crippled spaceship would swing around the moon and let momentum whipsaw it back to earth. But that hadn’t been in the plan, and a wrong calculation would send it past the moon and forever into deep space.

Even as the astronauts shut down the service module and squeezed into the LEM, ground workers frantically worked out the logistics of staying alive. The crew would have to ration water, which was not only for drinking but also rehydrating food and cooling equipment. And shut down every electrical device that wasn’t critical. Including the heat.

The LEM dropped to 40 degrees and water condensed on its walls.But they had one big problem. They were breathing it. The LEM’s air system was built for two people for two days. Now three people would be in it for four days. And exhaling. Devices in the LEM wouldn’t be able to remove the carbon dioxide.

There were plenty of devices in the command module. But they didn’t fit the LEM. They were — literally, in some cases — square pegs in round holes. And time was running out. That conundrum inspired what perhaps was the most inspiring part of the rescue, and one that even today honors American can-do.

People who’ve seen the movie will recall a supervisor upending a box and spilling out all the hoses, spacesuits, rolls of tape and pieces of cardboard that were available to the astronauts far off in space. In about an hour, the ground crew rigged something that probably wouldn’t win a high school engineering competition, but it worked.

Soon the astronauts had replicated the contraption on board, and literally could breathe easy. And just in time. Somehow, the three men toughed it out to the morning of April 17, and Adan swelled with emotion as they bid farewell to Aquarius, the LEM, which had served them so nobly.

“After all the work we have done, it paid off,” Adan recalled. But now came perhaps the most treacherous part. Just as aim had been critical as the spacecraft did its slingshot around the moon, the crew now had to do just the right course corrections as it approached Earth. Come in at too sharp an angle, and Odyssey burned up. Come in at too oblique an angle, and it skipped off the atmosphere and back into space, and oblivion.

Adan recalls years later, sitting in a theater, watching the 1995 Ron Howard movie about the rescue. In the film, Mission control workers, reporters, and the astronauts’ relatives sit, white knuckled, waiting for the moment when they’ll see the spacecraft floating safely to the ocean. And there’s jubilation when the image appears.

“Oh God, yeah. Very emotional. It was difficult to describe,” he said. “It was my baby. It saved those guys.”

“It paid off.”

Not long after Apollo 13’s return, the three astronauts, who already had had a reunion with their Mission Control rescuers in Houston, returned to the Kennedy Space Center to thank the rest of the people who’d played a part as well.

Adan eventually left Grumman to work for another firm on the space shuttle, and later worked on the Hubble telescope. He spent a decade in Saudi Arabia, and moved about two decades ago to Palm Beach County, where his daughter founded a charter school in the Lake Worth Beach area.

As with many veterans of the space program, Adan bemoans the premature end to Apollo. He praised the shuttle program, which replaced dramatic missions with workaday space activities, and made huge strides. But he said America should have continued to aim to the stars.

“Look how much we learned,” he said.”If Grumman had continued the space program, right now we’d be on Mars, colonizing the moon, and beyond … Things would have been so different.”

Adan said the talent is there. And the will. It could be done.

“Oh, hell yes,” he said.

In 2009, at an event on the Space Coast. Adan ran into Fred Haise, who’d never gotten the chance to pilot the LEM to the moon on Apollo 13. Haise told him, as he’s said so many times, that Adan and his colleagues flat-out saved Haise’s life.

“Fred Haise said, ‘You guys did it. Without you guys we’d never get back alive.”

©2020 The Palm Beach Post (West Palm Beach, Fla.) – Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.