Back in 1987, the world was a very different place. While the Soviet Union was on a crash course with destiny, the power the nation wielded — backed by a massive nuclear arsenal — had left it in a decades-long staring match with the United States.

Mutually Assured Destruction, a doctrine of military strategy that left the two nuclear powers in a stalemate President Ronald Reagan described as a “suicide pact,” had left the world in an uneasy state of both peace and war simultaneously. And nowhere was this dichotomy more present than in the homes of residents of East and West Germany. The nation had been divided since the end of World War II, with NATO’s Western powers in West Germany, and a Soviet puppet-state called the German Democratic Republic in the east.

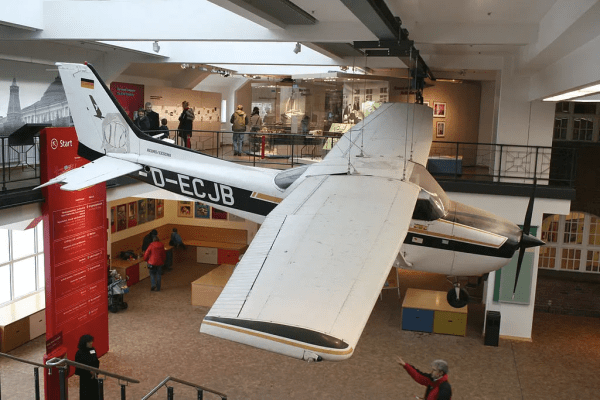

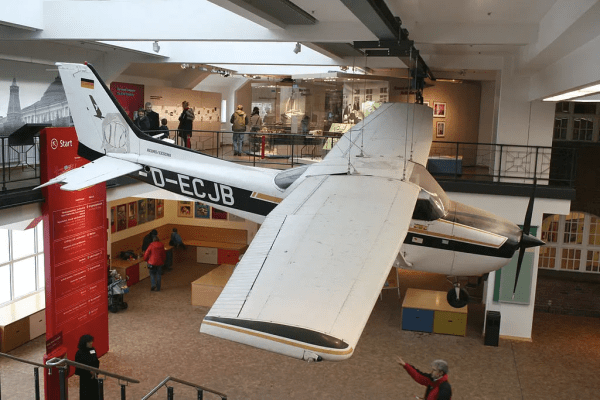

By 1987, the wheels that would ultimately tear down the Berlin Wall dividing East and West Germany physically and ideological were already turning, and a young man named Mathias Rust was keen on playing his part in history. Like many young adults, Rust was increasingly politically minded. Unlike most 18-year-olds, he also had a pilot’s license and access to a Cessna 172 airplane that had been modified by removing the rear seats for added fuel capacity.

In October of 1986, Rust had watched the Reykjavík summit between U.S President Ronald Reagan and Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev. As that summit ended in a stalemate, Rust felt the overwhelming urge to find a way to make a difference.

“I thought every human on this planet is responsible for some progress and I was looking for an opportunity to take my share in it,” he would go on to tell the BBC.

Rust soon began forming a plan. President Theodore Roosevelt once famously said, “Do what you can, where you are, with what you have,” and while it’s unlikely that Rust was aware of the axiom, his actions embodied the premise. He took stock of the skills he had, the resources he had available, and the situation to begin forming an idea. He’d take his little Cessna directly into the heart of the Soviet Union in a political spectacle he hoped would inspire others.

“I was thinking I could use the aircraft to build an imaginary bridge between West and East to show that a lot of people in Europe wanted to improve relations between our worlds,” Rust said.

By May 13, 1987, Rust was ready to put his plan into action, but he still harbored understandable doubts. Today, Russia is renown for their advanced air defense systems, and the same was true of their Soviet predecessors. The USSR maintained the most elaborate and largest air defense system anywhere on the globe and they had demonstrated a propensity for using it against civilian aircraft. Only about five years earlier, the Soviets had shot down a South Korean airliner that had strayed into their airspace, killing all 269 passengers on board.

Rust told his parents he was leaving on a tour of Northern Europe that would help him accumulate more hours toward his professional pilot’s license, and for the first few days, that’e exactly what he did. After a few days of traveling, he stayed in Helsinki, Finland for a few days and pondered what he was about to do. He wanted to make a big public statement, but he wasn’t keen on dying in the process.

“Of course I was afraid to lose my life. I was weighing if it is really responsible, reasonable, to take this kind of risk. At the end I came to the conclusion, ‘I have to risk it,’” he said.

He filed a flight plan that would have taken him to Stockholm and took off just like he would on any other day. As Rust recalls, he still wasn’t really sure he would go through with it until well after he was already airborne.

“I made the final decision about half an hour after departure. I just changed the direction to 170 degrees and I was heading straight down to Moscow.”

It wasn’t long before Soviet air defenses were alerted to his presence. They were tracking him on radar, and within an hour of diverting from his flight plan, fighters had been scrambled to intercept his little Cessna. He was flying low — only about 1,000 feet off the ground or 2,500 feet above sea level, and donned his crash helmet.

“The whole time I was just sitting in the aircraft, focusing on the dials,” said Rust. “It felt like I wasn’t really doing it.”

Fate was on Rust’s side, however, and one of the fighter pilots reported seeing what he believed was a Yak-12 — a Soviet plane that looks similar to a Cessna 172. Either the pilot or his air traffic controllers decided that the plane must have been allowed to be there, because they broke off pursuit. At around the same time, Rust descended below the clouds to prevent them from icing up his wings, which also made him disappear from Soviet radar. Once he passed the clouds, he climbed back up to 2,500 feet and popped back up on their radar scopes.

Suddenly, he spotted fighters emerge from the cloud cover in front of him.

“It was coming at me very fast, and dead-on. And it went whoosh!—right over me. I remember how my heart felt, beating very fast,” he explained. “This was exactly the moment when you start to ask yourself: Is this when they shoot you down?”

Before he knew it, Soviet Mig-23 interceptors pulled up alongside him from both beneath him and his left. The single-seat, swing-wing Mig-23 was capable of speeds in excess of Mach 2.3 (more than 300 miles per hour faster than an F-35) and was positively massive compared to Rust’s little Cessna. In order to flank him, the Migs had to lower their landing gear and extend their flaps to scrub their speed enough not to scream past Rust and his single-prop 172.

“I realized because they hadn’t shot me down yet that they wanted to check on what I was doing there,” Rust said. “There was no sign, no signal from the pilot for me to follow him. Nothing.”

Rust would later learn that the pilots were indeed trying to contact him, but were using high-frequency military channels. Finally, the Migs pulled their landing gear in, dropped their flaps and screamed off into the distance again, circling rust twice in half-mile loops before departing. Rust had once again made it through a brush with Soviet interceptors and was still flying straight for the Soviet capital.

A later investigation would confirm that, either the pilots assumed the Cessna was indeed a Soviet Yak-12, or their command didn’t think the situation warranted any concern. Shortly after the fighters departed, luck would once again deal in Rust’s favor. He unknowingly entered into a Soviet air force training zone where aircraft with similar radar signatures to his own were conducting various exercises. His small plane got lost in the radar chatter, which would save his neck in the following minutes.

Protocol required that all Soviet pilots reset their transponder at frequent intervals, and any pilot that didn’t reset theirs would immediately show as hostile on radar. At 3pm, just such a switch was scheduled, but because Rust was flying among a group of student pilots, the Soviet commander overseeing radar operations assumed he was a student that had absent-mindedly forgotten to switch his transponder. He ordered the radar operator to change Rust’s radar return to “friendly,” warning that “otherwise we might shoot some of our own.”

An hour later, Rust was little more than 200 miles outside of Moscow, and subject to a new region’s radar and air defense scrutiny. Once again, radar operators spotted the small aircraft and intercept fighters were dispatched, but the cloud cover was too thick and they were unable to find the small Cessna visually. Soon thereafter, another radar operator would mark Rust’s plane as “friendly,” mistaking it for a search and rescue helicopter that had been dispatched to the region.

As Rust approached Moscow’s airspace, the report that was forwarded to the air defense in the area listed a Soviet aircraft seemingly flying with its transponder off, rather than anything about a West German teenager infiltrating hundreds of miles of heavily guarded Soviet airspace.

Rust then flew his small plane over Moscow’s infamous “Ring of Steel,” which was made up of multiple overlapping air defense systems built specifically to protect the Soviet capital from American bombers. Air defense rings surrounded Moscow at 10, 25, and 45 miles out, all capable of engaging a fleet of heavy bombers, but none the least bit interested in the tiny plane Rust piloted.

Shortly thereafter, Rust entered the airspace over the city itself — an area that had all air traffic heavily restricted, even military flights. As Rust flew over Moscow, Soviet radar operators finally realized something was terribly amiss, but it was too late. There was no time to scramble intercept fighters; Rust was already flying from building to building, trying to identify Moscow’s famous Red Square.

“At first, I thought maybe I should land inside the Kremlin wall, but then I realized that although there was plenty of space, I wasn’t sure what the KGB might do with me,” he remembers. “If I landed inside the wall, only a few people would see me, and they could just take me away and deny the whole thing. But if I landed in the square, plenty of people would see me, and the KGB couldn’t just arrest me and lie about it. So it was for my own security that I dropped that idea.”

Rust spotted a 6-lane bridge that led into Red Square with sparse traffic and only a few power lines he’d need to avoid. He flew over the first set of wires, then dropped the aircraft down quickly to fly below the next set. As he nearly touched down, he spotted a car directly in his path.

“I moved to the left to pass him,” Rust said, “and as I did I looked and saw this old man with this look on his face like he could not believe what he was seeing. I just hoped he wouldn’t panic and lose control of the car and hit me.”

With his wheels on the ground, Rust rolled directly into Red Square. He had wanted to park the plane in front of Lenin’s tomb, but a fence blocked his path and he settled for coming to a stop in front of St. Basil’s Cathedral. He shut down the engine and closed his eyes, taking a deep breath as the reality of his situation slowly engulfed him. He had done the impossible.

“A big crowd had formed around me,” Rust recalled. “People were smiling and coming up to shake my hand or ask for autographs. There was a young Russian guy who spoke English. He asked me where I came from. I told him I came from the West and wanted to talk to Gorbachev to deliver this peace message that would [help Gorbachev] convince everybody in the West that he had a new approach.”

He had anticipated being captured immediately by the KGB, but instead found the crowd confused and delighted by his stunning entrance. One woman gave him some bread. A young soldier chastised him for not applying for a visa, but credited him for the initiative. What Rust didn’t realize was that the KGB was already present, and agents were already worming through the crowd, confiscating cameras and notebooks people had Rust sign.

An hour later, two truck loads of Soviet soldiers arrived. They mostly ignored Rust as they aggressively pushed the crowds back and put up barriers around the teenager and his plane. Then three men arrived in a black sedan, one of whom identified himself as an interpreter. He asked Rust for his passport and if they could inspect the aircraft. Rust recalls their demeanor as mostly friendly and even casual.

The plane was then taken to the nearby Sheremetyevo International Airport where it was completely disassembled during its inspection, and despite the friendly demeanor of the Soviets, he was immediately transported to Lefortovo prison. The prison was infamous for its use by the KGB to hold political prisoners.

Initially, the Soviets refused to believe that Rust had accomplished his daring mission without support from NATO forces. The date he chose, May 28, was Border Guards Day in the Soviet Union, and they accused him of choosing the day intentionally to embarrass them. Then they accused him of getting the maps he’d used to reach Moscow from the American CIA… that is, until the Soviet consul in Hamburg confirmed that they could purchase the very same maps through a mail order service.

After realizing Rust was not the world’s youngest and most ostentatious CIA operative, they finally charged him illegal entry, violation of flight laws, and “malicious hooliganism.” Rust pleaded guilty to the first two charges, but refused the third, claiming he had no malicious intent. Nonetheless, he was found guilty on all counts by a panel of three judges and sentenced to four years in the same Lefortovo prison. Despite the prison’s harsh reputation, Rust was mostly well cared for, and even allowed to have his parents visit every two months.

In 1988, Rust was released from prison in a “goodwill gesture” following a treaty between Reagan and Gorbachev that would have both nations eliminate their intermediate-range nuclear missiles. It was not quite such a happy ending for many Soviet officials however.

In a way, Rust’s flight did exactly what he’d hoped. The stunt had seriously damaged the reputation of the Soviet military and provided Gorbachev with the leverage he needed to outfox those who opposed his reforms.

Almost immediately following Rust’s landing in Red Square, the Soviet defense minister and the Soviet air defense chief were both removed from their posts for allowing such an egregious violation of Soviet airspace. Shortly thereafter, hundreds of other officers were also removed from their positions. Rust’s flight led to the single largest turnover of Soviet officers since the 1930s, according to Air & Space Magazine.

Rust would never sit behind the stick of an aircraft again, but would go down in history as the only pilot to defeat the entirety of the Soviet military using a rented single-prop trainer plane. Unfortunately, Rust’s seemingly heroic stunt has been overshadowed by the troubled man’s continued run-ins with the law. In the early 90s, he received another prison sentence for assaulting a woman that refused his romantic advances. In 2005, he was again convicted of a crime — this time for fraud. Today he describes himself as an analyst for an investment bank, seemingly keen to leave his high-flying theatrics behind him.

This article originally appeared at Sandboxx

More articles from Sandboxx: