The debate about whether or not video games improve your cognitive abilities is over. It turns out they can make you quicker and more decisive. And as a result, the military has begun testing and using virtual reality programs to train soldiers. And while you may think that video games or simulations don’t compare to actual field training, experts within the military community suggest that you’d be wrong.

“We have somewhat solid data to support the notion that playing video games in fact actually improves your cognitive processes and your visual processes,” said Dr. Ray Perez, program manager at the Office of Naval Research’s Cognitive Science of Learning Program, in an interview with Task & Purpose.

“Video game players are far superior to non-video game players in the ability to process things like field of vision, being able to hold digital objects in your memory. They can process information faster,” he added.

And that’s where virtual and augmented reality come into play.

Perez said that his team is working on simulations of virtual military environments. Soon he hopes to better understanding of exactly how video games in virtual realities affect the brain and how they increase soldier’s abilities

“The modern naval force has grown up with computers at home, video games, arcades and head-mounted displays in their personal life,” said Dr. Lawrence Schuette, director of research at ONR in a statement. “Coming to float and seeing it on board ship is just a logical extension.”

Noting that games can help increase capacity for speed and efficiency, the next question for ONR, according to Perez, was, can we train that capacity and that skill?

Usually in the event that a person can do something faster, he or she often has the trade-off in quality, meaning that faster activities result in more errors — a phenomenon called “speed-accuracy trade-off.”

However, video game players typically are not susceptible to this occurrence.

“They increase their speed but they don’t commit more errors,” Perez said.

And although ONR still has a great deal of analysis and development ahead, its scientists are already turning video games into learning tools for today’s military personnel.

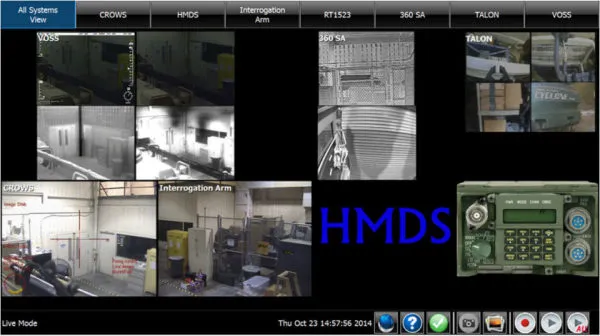

“When people think of virtual reality, many imagine Tony Stark from the ‘Iron Man’ movies, hands raised and moving virtual displays projected in front of him. While that might be fanciful now, Navy engineers are working hard to develop such capabilities,” according to an ONR statement.

Related: The History Of Video Games And The Military »

ONR right now is employing several games for practical application in its training processes, including one that teaches damage control, and another for improving field surgical skills.

“One of the things we think that simulators are very good at is because they’re computer based… you can sit before a computer screen and play through multiple scenarios,” Perez added.

But there are more benefits to using simulators than just variable practice. They save money, are much less dangerous to trainees, and allow specific cognitive skills to be targeted. What’s more, real field equipment is fragile and harder to replace than simulators.

“When we talk about simulation, we talk about degrees of immersion. It’s the feeling of being in a simulation, and you suspend your disbelief that you’re in an artificial world. If it’s designed properly … the trainees really feel as if they are in combat, in a real-life situation,” Perez said.

Still, there are downsides.

“Unfortunately, we have not been able for the most part to demonstrate the effectiveness of virtual reality. And furthermore, we haven’t figured out the magic sauce,” Perez said. “There’s always this belief that the more real it is, the more powerful it will be as a trainer. Not so. We know the more complex and real you make something, it is harder for novices to learn from those environments.”

Because of how complex and distracting a realistic simulation can be, new recruits are not often able to discern how to complete their missions, because they are trying to observe everything at once. Instead of watching for small but apparent relevant clues, they miss cues because they are simply overstimulated. Trainees could spend hours in a simulation like this and learn absolutely nothing.

“If you plot an expert into a very complicated, rich environment, he knows what to look for from experience. He is not distracted by irrelevant cues or irrelevant information,” Perez said. “Not so with the novices. He’s overloading his cognitive processes. So he’s trying to take it all in.”

According to Perez, training needs to be a process of building upon small fundamentals, even in the world of virtual reality. And striking a balance between rich environments and one that can help trainees learn is what ONR hopes to accomplish over the next several years.

“Virtual reality is really cool,” Perez said. “What we don’t know is what really facilitates the learning. Is more less, or is less more depending the domain?”