In late 2017, John McCain and Jerry Moran, two senior Republican senators on the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee, penned the first draft of what would become the VA Mission Act, a transformational law that paved new pathways to private sector healthcare for veterans.

The Mission Act essentially made permanent the VA Choice Act, a controversial 2014 law passed in the wake of a wait-time scandal at a Phoenix veterans’ hospital. The Choice Act became unpopular among veterans’ advocates for a variety of reasons, including that it represented a major step towards the privatization of VA services.

Among the harshest critics of Choice was the American Legion, the oldest and, arguably, most influential veterans’ organization in America.

In 2017 congressional testimony, Legion legislative staffer Jeff Steele tore into the law’s many problems, declaring veterans “have not found [Choice] to be a solution.”

“Instead,” Steele said, “they have found it to create as many problems as it solves.”

Perhaps hoping to stem any criticism, McCain and Moran sought feedback on their legislation from the Legion before making it public. After the organization’s then-legislative director, Lou Celli, read a draft bill at home over one weekend, he felt it went against the best interests of veterans, and would further crack open the door to privatization. A major complaint of Celli’s was that the bill completely stripped the agency of the right to coordinate care for veterans based on medical need.

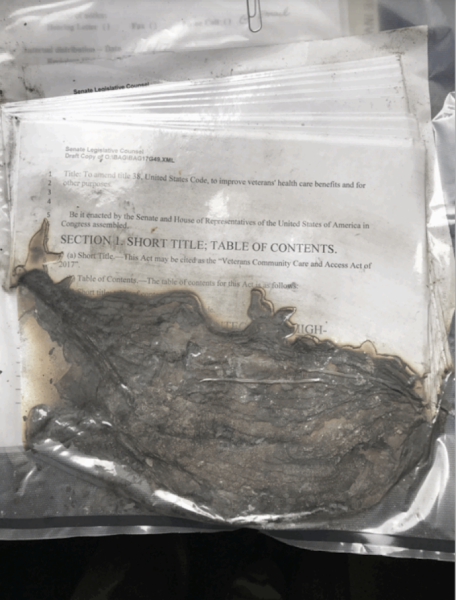

Rather than communicate those concerns productively, Celli, in an apparent act of anger, took the bill out into his backyard, and lit it on fire. The legislation’s ashy remains were then photographed, and eventually circulated around Capitol Hill.

The stunt upset Senate staffers, including former McCain aide Drew Trojanowski, who later moved into the White House as an influential assistant to President Donald Trump. (Moran, meanwhile, is largely expected to become the next chairman of the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee once the current Republican chairman, Johnny Isakson, steps down.)

The act deeply hurt Celli’s credibility on the Hill, and significantly weakened the organization’s hand at a crucial time for veterans’ policymaking.

“That bill-burning, well, burned some bridges,” one former Legion staffer said. “I was frankly offended that Celli wasn’t fired for that.”

A second former Legion staffer said the burning “made a lot of people in Washington upset,” while a third said that, as the Mission Act moved forward, “the Legion had lost a lot of bargaining power” and essentially had to support the bill as repentance.

Indeed, on December 4, 2017, when the McCain-Moran bill was publicly introduced, the American Legion was one of just three veterans groups to publicly endorse it (The other two groups were AMVETs and the Koch-backed Concerned Veterans of America, a conservative group that Celli and other traditional veterans’ advocates have long seen as ideologically driven to privatize the agency).

“None of the major veterans’ service organizations liked that McCain-Moran bill, but then suddenly the Legion came out in support of it,” said one veterans advocate on Capitol Hill who has worked with the Legion. “It felt like the Legion was indebted to those offices, and made good with that support. It certainly enabled a more conservative drafting of the Mission Act. Instead of us having a united front, we suddenly had the largest veterans group supporting the most conservative path forward.”

Celli did not respond to multiple emails and John Raughter, a Legion spokesman, declined to provide him for an interview. However, Raughter said the Legion was proud of its support of the Mission Act, which was signed into law last year.

“The Legion fights for what’s good for veterans and what’s good for our country,” he said.

* * *

The American Legion was founded more than 100 years ago, in Paris on March 15, 1919, by a group of battle-drained World War I veterans. Its ranks quickly ballooned, and, by the end of World War II, 3.3 million veterans called themselves active Legion members. As membership dues poured in, the Legion set up outposts across the country and constructed an unrivaled influence machine over veterans’ policy in Washington.

Early Legion advocacy was key to the creation of the Department of Veterans Affairs and the passage of the G.I. Bill. In 1977, when a proposal sought to relegate the Veterans Affairs Committees to subcommittee status, the “Big Three” veterans groups in Washington — the Legion, Veterans of Foreign Wars, and Disabled American Vets — organized a phone-in that jammed the Capitol Hill switchboard and halted the policy.

One year later, a similar blitz by the “Big Three” halted Congressional efforts to weaken veterans’ longtime federal hiring preference.

But the organization is now a shell of its former self, according to public and internal Legion documents, and nine current and former Legion staffers who spoke with Task & Purpose on condition of anonymity.

As the Legion publicly heralds its 100th anniversary with special events and commemorative swag, it faces diminishing political influence, financial challenges, and a deep political and generational divide between the younger, more open-minded policy wonks in its Washington office and the aging, more conservative staffers at the Legion’s Indianapolis headquarters.

The D.C. workplace also suffers from its own internal problems. The office has a high turnover rate, with at least four staffers leaving in the last 18 months alone (Just this week, the organization’s new legislative director, Karl Cooke, was unceremoniously ousted amid a power struggle with Celli).

This exodus is fueled, in part, by Celli, whose hostile and brash demeanor has invited comparisons to a mafia don.

“Lou’s got pictures of the Godfather and Tony Montana on the back of his office door,” one Legion source said. “He’s a bully. He’s a guy who pushes people around. He’s the guy who calls you a name, then two days later comes back to apologize.”

Another source told Task & Purpose there’s an informal “Celli mafia” of loyalists who will “stab in the back” those who cross him.

Celli’s hardscrabble tactics have also extended to Capitol Hill encounters. Sources say Celli likes to lay down the threat that, should the Legion not get its way on a policy matter, he will flex the Legion’s political muscle, deploy millions of angry members, and cause political pain.

To some, this is the right approach, but others see it as an empty threat.

“When Lou bragged about the Legion’s membership, everybody else in the veterans’ space rolled their eyes,” said one former staffer at a competing veterans’ organization. “We all know they don’t have as many members as they claim.”

According to its official tally, the Legion has lost more than 700,000 members over the last decade. While the Legion publicly proclaims it has “over 2 million members,” the true number stands at around 1.8 million. In fact, the Legion hasn’t been over the two million-member mark since 2016, according to its most current membership record, and one former Legion staffer said the organization is “bleeding members.”

The Legion’s membership numbers are reported on some parts of its website as “nearly 2 million,” while others say “over 2 million.” But the organization often uses the latter figure on Capitol Hill, according to sources.

“Lou and leadership are dead set on using the two million number even though it’s false,” another former Legion staffer said.

Even with membership under two million, the Legion is still a powerful player in Washington.

But former Legion staffers say the organization sporadically announces “action alerts” only to then spam members with a half-dozen emails in one week. By not carefully cultivating an active base of members, two sources said the Legion’s email list has become smaller and less engaged in recent years. Both said the Veterans of Foreign Wars is better at organizing its members.

“People on the Hill have started to realize Lou’s threats were empty, and that the Legion is a paper tiger,” said a staffer for another veterans’ service organization. “They really don’t have the infrastructure to punch back anymore.”

Celli’s brusque attitude translated to his Twitter account, which also got him in hot water.

Last May, after the bill burning, a former White House official complained anonymously to the Washington Examiner about Celli’s anti-Trump tweets, which they said had hurt the Legion’s standing in the White House. The article also dredged up other Trump-critical tweets by Legion staffers. While the commander-in-chief has historically held annual sessions with the Legion’s commander, Trump skipped at least one of these meetings because, according to a former Trump administration official, “the White House doesn’t respect the Legion.”

The Examiner’s story raised hackles in Indianapolis, and panicked staffers sought to squelch social media in the D.C. office entirely. The Legion effectively initiated a freeze on all Twitter use by Washington staffers, with mixed results. Celli deleted his Twitter account, but others didn’t.

Shortly thereafter, the Legion’s D.C. Twitter account, which offered policy updates and weekly lighthearted live streams from staff, went dormant. Raughter, the Legion spokesman, said the account was shuttered because the Legion “has one voice.”

“It didn’t make sense to have different accounts for different buildings,” he said.

While some believe Celli has learned from his missteps and earnestly sought to repair his relationships and reputation on Capitol Hill, others think he needs to go.

“He’s a bit of an attack dog, but Lou is really bright,” a former Legion staffer said. “Some people love him, some people hate him. I thought he was pretty calculated and effective. He was the one who got the Legion onboard with medical cannabis.”

Another former Legion staffer took a different tact: “Absent getting rid of Celli, they are just painting over rust, as they say in the Navy,” he said. “Celli keeps us out of more meetings than he gets us into,” a third staffer grumbled.

Lou CelliPhoto: CSPAN

Despite some missteps, Celli was promoted to executive director at the Legion last July, and some believe he is in line to become national adjutant. One reason he was able to weather the storm, sources say, is due to his support among a shadowy cadre of powerful Legionnaires known unofficially as the “God Squad.” (According to sources, at least one member of the squad is fond of Celli).

This set of septuagenarians is composed of former national commanders including Jake Comer, Dan Dellinger, and Dan Ludwig. This informal group has deep connections in the Legion community and is adept at navigating the Legion’s arcane constitutional process and by-laws, which run 28 pages long.

To illustrate their outsize power, three sources told Task & Purpose the “God Squad” has already handpicked the next three or four national adjutants, despite the fact that the decision is put up for a vote by the National Executive Committee. “The elections are all pomp and circumstance,” one source said.

The Legion’s priorities have always been dictated by resolutions, which require buy-in from members across the country and discussion in various Legion bodies and committees before facing ratification at the national level. One issue that saw resounding support from members was medical marijuana, which many veterans’ swear by as an alternative treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder.

In November 2017, the Legion held a press conference in the chamber of the House Veterans Affairs Committee to share results of a survey indicating overwhelming support by membership for further research into the leafy green substance.

At the time, many inside the organization were hopeful that supporting cannabis research could help attract thousands of new, younger Legion members. Weeks later, the Legion passed Resolution 11, which urged greater federal study of medical cannabis.

While the resolution still appears on the Legion’s website, three Legion staffers said the resolution has been scrubbed from the organization’s internal list of lobbying priorities — effectively ending Legion efforts that could lead to further legalization of medical marijuana, which 92% of veterans support — on orders from the “God Squad.”

“They said they didn’t want us working on cannabis, no ifs, ands or buts,” a former Legion staffer said. “All our work with Congressman [Lou] Correas’ office and Rep. Phil Roe stopped. We weren’t allowed to talk about cannabis or take meetings on it.”

Legion spokesman Raughter suggested that the cannabis resolution was deemphasized because, “It was so misunderstood and twisted out of context by media outlets.” He declined to elaborate.

Younger staffers have put forth other policy and strategic ideas to win over younger veterans, only to be silenced by aging leaders. On the policy side, staffers sought to wade more deeply into the issues of opioid addiction and suicide prevention, two issues that disproportionately impact veterans.

Instead, two former Legion staffers say these initiatives were slow-walked or outright rejected.

Another top initiative for younger staffers was to recruit more members on college campuses and transform Legion posts from dark, smoky bars for telling old war stories to brighter, family-friendly spaces. Neither effort has been widely embraced, though there has been some impressive work by younger vets at the local level, including the rehabilitation of Los Angeles‘ Post 43, which has been deemed “Hollywood’s Hottest Private Club.”

“There’s a lot of ageism in the Legion,” one former staffer said. “At some point, I was sick of the status quo. It felt like I was paddling a canoe upriver by myself.”

Amid this flurry of ideas from young staffers, leadership often seemed most focused on divisive political and cultural issues that had little to do with the quality of life for members. This is not new for the Legion.

During the 1920s, the Legion heavily promoted Americanism, sought to restrict immigration, and blocked public forums for leftist speakers. Some of the group’s leaders openly promoted fascism as an effective tool against the left, and, in 1930, the Legion invited Italian fascist Benito Mussolini to speak at its annual convention. More recently, in 2011, the Legion opposed the repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.”

In 2016, the Legion’s national commander criticized Colin Kaepernick’s decision to kneel during the national anthem as “a vicious attack on law enforcement.” (The Legion’s battle with Kaepernick prompted a scathing takedown in Foreign Policy by Legion member Kyleanne Hunter titled simply “What the Hell is Wrong with The American Legion?”)

The Legion also outlined a Trumpesque immigration policy that was sourced largely from the Federation for American Immigration Reform, which the Southern Poverty Law Center has deemed a hate group. And last August, the Legion awarded its Religious Freedom Award — a gold-plated .22 caliber rifle — to President Donald Trump for “advancing religious freedom throughout our federal agencies and government.”

* * *

For a time, Verna Jones was seen as the one leader who could bridge generations and bring the Legion into the future. With women and minorities representing some of the fastest-growing demographics in the military, Jones, a Gulf War veteran, was poised to be the first black woman to become the Legion’s national adjutant.

Jones’ ascent was seen by some as an opportunistic effort by the organization to build a relationship with the Obama administration; some say her value was diminished once Trump was elected. Sources say Jones faced implicit and explicit sexism and racism in the Legion, but steeled herself for this behavior, and was generally seen as a competent and supportive leader.

Her remarkable rise through the organization ended last summer after Task & Purpose reported that Jones falsely claimed to be a lawyer on multiple occasions. She was almost immediately drummed out of the organization and replaced by Celli.

“What’s so terrible is Verna proved the bigots inside the organization correct,” a former Legion staffer said. “It now will be so much more difficult for the next African American leader to rise through the ranks of the organization.”

Jones’ resignation came in the summer of 2018, just days after the Legion announced it would lay off 15 percent of its staff.

A month before the layoffs, the organization produced an internal income sheet, obtained by Task & Purpose, that raised alarms over declining revenue.

The income sheet showed some areas of revenue growth over the previous year, including contributions and royalties.

Yet the organization’s top revenue generator — membership dues — was down nearly four percent, or more than $800,000, from the previous year. Related “membership services” revenue was down more than 66 percent, or roughly $200,000.

Other declining revenue streams included “magazine income,” “label and printing program,” and program income. Overall, the organization’s gross profit was down more than $1.7 million dollars over the previous year while expenses had shot up by nearly eight percent, or $3.2 million.

“They are not in a good financial position right now,” a former Legion staffer said.

The Legion’s financial worries were announced in a conference call hosted by then-National Commander Dan Wheeler, who simultaneously informed staff of impending layoffs while announcing new high-paying positions for a number of senior staffers, including Celli.

That day, as staffers anxiously pondered their futures in the organization, Celli posted a celebratory picture featuring champagne and oysters on social media, which angered many. (Sources say Celli later apologized for this tweet.)

Two Legion sources expressed annoyance at Celli’s predilection for fancy Washington lunches and high-end Uber black cars purchased on the company credit card. One former Legion staffer said Celli would routinely dine at expensive Washington eateries for work lunches, while others would be reamed out over relatively minor expenses.

“The Legion doesn’t have good policies in place on how to spend money,” the former staffer said.

The Legion’s financial and political challenges are far from insurmountable, and some Legion staffers expect many of the millions of post-9/11 veterans to eventually sign up to become Legion members. There’s also a congressional effort being led by Sen. Krysten Sinema (D-Ariz.) to expand the Legion’s strict eligibility requirements for all honorably discharged veterans who served during unrecognized times of war since World War II.

Raughter, the Legion’s spokesman, brushed off the notion of financial concerns inside the organization, pointing out that the organization delivered more than $1 million in financial assistance to 1,713 Coast Guard families impacted by January’s government shutdown. (This money was largely raised through donations in reaction to the shutdown, and came from the Legion’s Temporary Financial Assistance fund.)

“We have three times as many American Legion posts as there are Walmarts,” Raughter said. “We aren’t going anywhere.”

He further argued that the Legion has been counted down and out many times before, as evidenced by a 1971 Wall Street Journal article entitled “American Legion, Once Civic and Social Power, Is Slowly Fading Away.”

Yet some in the Legion’s world think the organization is past its prime.

“We used to be a leader,” a current Legion staffer said. “Now we ride coattails.”

Correction: Due to an editing error, this article has been updated to reflect the mention of Sen. Jerry Moran, not Sen. Jim Moran, and the Legion position of national adjutant, not national commander.