There are many ways America honors its service members, a spectrum even, that runs from more to less appropriate or meaningful. Certainly military cemeteries and national monuments and holidays have been codified into American DNA as ways that we celebrate and honor our vets. More recently, on the other end of that spectrum, professional sports franchises have been celebrating the military in cheap on-field gimmicks that senators John McCain and Jeff Flake have dubbed “paid patriotism.”

Related: Vets need to cool it with outrage on social media »

Writing as a veteran, I understand how easy it is to become cynical about the ways that civilians honor our service — or don’t, as the case may be. I don’t know how many times people have thanked me for my service on Memorial Day. You appreciate the sentiment, but it can hurt that that’s all it is: an uninformed sentiment. It’s easy to let this cynicism distort the logic of our expectations of what we deserve as veterans, to let our claims lose coherence. A meme I’ve seen on social media a lot lately is a prime example of this dynamic.

The meme is a direct response to the push for free college education for all; a clarion call that’s been given a huge platform since Sen. Bernie Sanders took it up as one of his campaign positions. But the meme is completely wrong for two reasons: People shouldn’t have to serve in the military in order to receive an affordable education and the meaning of your own service shouldn’t be predicated upon a free college education.

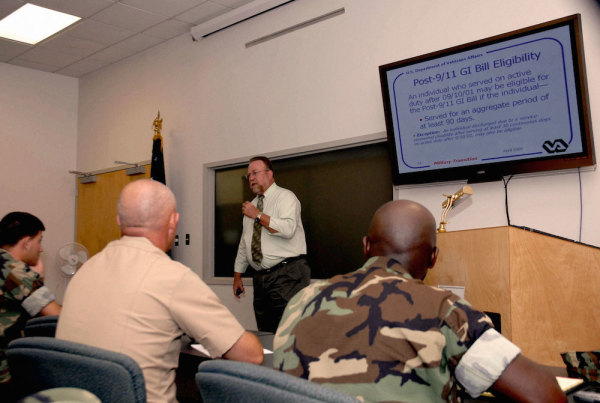

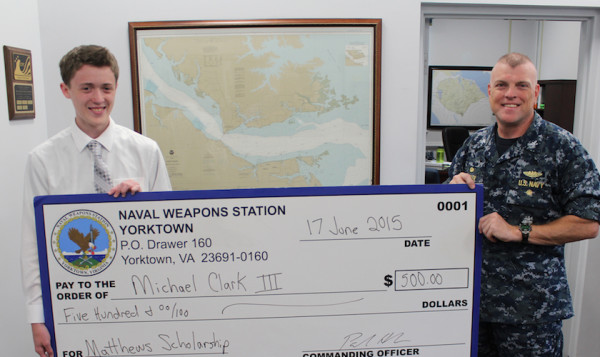

The kind of post-war or post-service benefits that veterans enjoy today are a relatively new thing. When President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 — what we informally call the G.I. Bill — it set the template for the educational and home-buying assistance benefits veterans receive today. One year of unemployment benefits, loans to start small business, cash-payments for college tuition; all this stuff was pretty revolutionary at the time, being a far sight better than anything veterans returning from World War I received.

But it was also revolutionary for the sheer number of Americans whose lives were affected by it. One in eight, or 16 million Americans total, fought in World War II. So the G.I. Bill wasn’t just a “reward” for defeating fascism; it was a way to sustain a strong democracy by implementing a massive program that would help to literally invent the American middle class.

But a few things have changed since 1944. Specifically, fewer people serve in the military, the cost of higher education has skyrocketed to astronomical proportions, and our manufacturing base has crumbled. These fundamental changes in the American economy and American demographics means that the G.I. Bill in its current incarnation plays a very different role in American culture than its predecessor did.

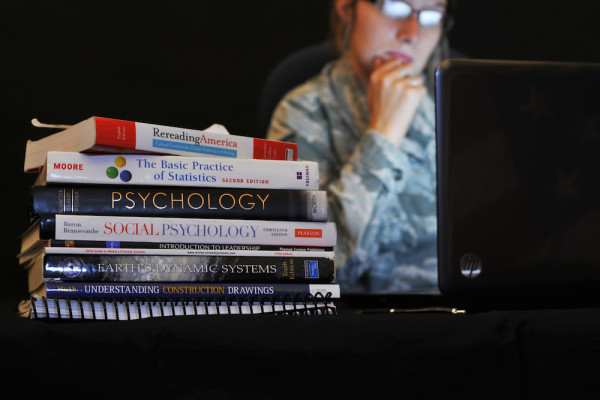

Let’s say that it’s 1949 and you’re a veteran who served with the 1st Infantry Division in Europe. Maybe you want to go to college. Maybe you want to go to a great college. University of Pennsylvania, an Ivy League school, charged $500 that year in tuition fees and $640 in room and board. Adjusting for inflation, that’s $4,907.15 for tuition and $6,281.16 for room and board in 2016 dollars. Not bad even if you don’t receive the G.I. Bill. But maybe college isn’t for you. That’s okay too because you can still be solidly middle class working in America’s booming post-war industrial economy.

Flash forward to present day. Instead of 12.5% of Americans serving, only roughly 1% have served since Sept. 11. And the story of astronomical college costs, rising over 170% since 1995, is a familiar one by now. University of Pennsylvania now charges about $50,000 a year for tuition alone. And all this comes at a time when college is increasingly mandatory to achieving economic stability. There simply aren’t as many manufacturing options as there used to be in America. As Derek Thompson pointed out in The Atlantic, “Manufacturing and agriculture employed one in three workers just after World War II. Today, those sectors employ only one in eight.” Basically, there are fewer jobs available for people without college degrees.

Getting your tuition paid, while something you deserve, isn’t in itself a validation of public service. Your service is much much bigger than that. And if that argument strikes you as too feel good, then consider this: Arguing on behalf of the limitation or unaffordability of college education makes America weaker, undermining the very purpose of your service. Maybe we should be looking at this from exactly the opposite angle and consider ourselves ambassadors of exploring new ways to make college affordable again. There’s plenty of room to debate whether or not college should be free, but it should be common sense that anyone who works hard enough to get into college should be able to attend.

Maybe our generation of veterans will push for that. It would certainly be good for the nation. And it might, in a way, even be a fitting tribute to our own service.