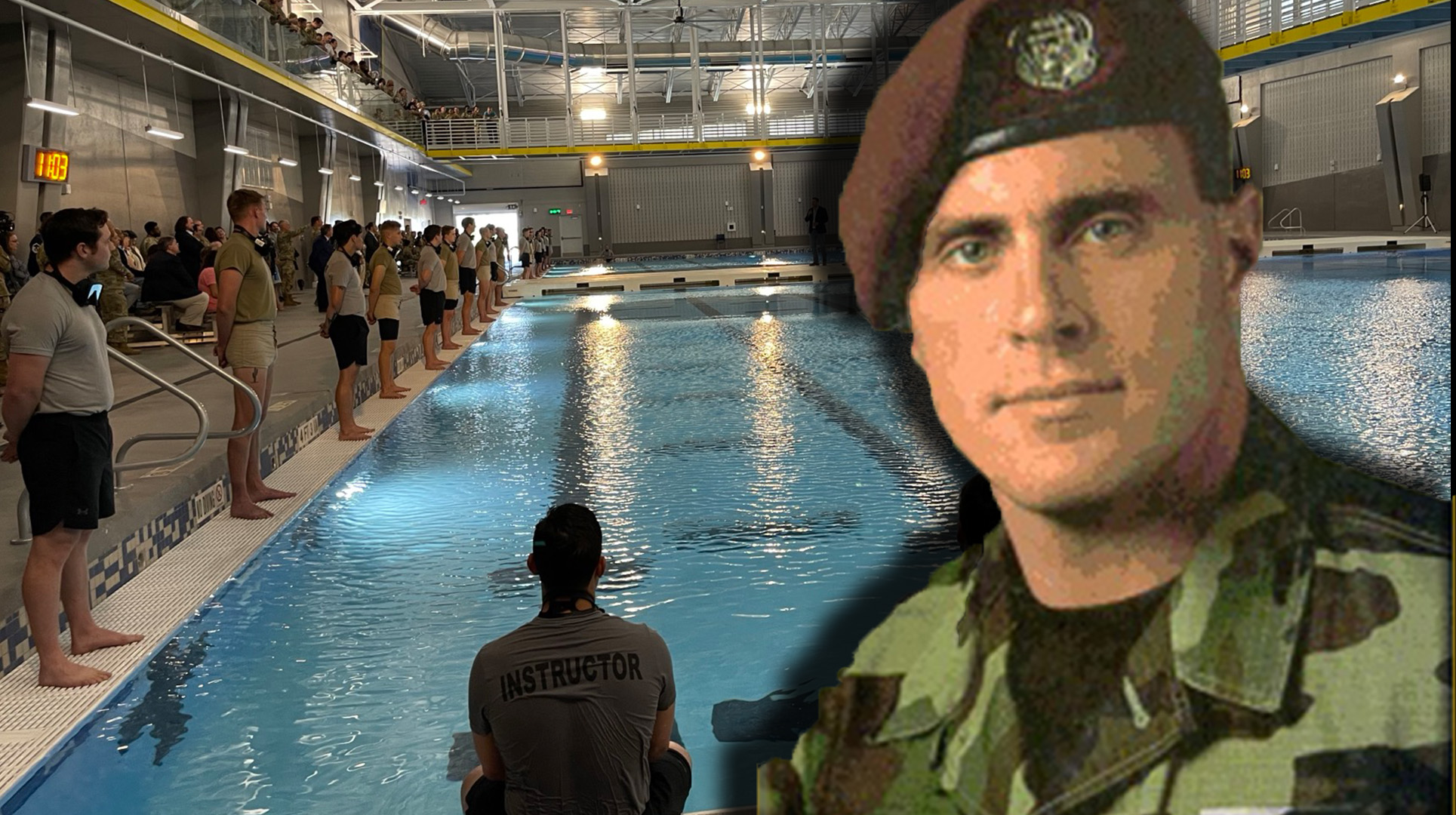

Mike Maltz was already a pararescue legend when he submitted his retirement paperwork in early 2003. But within days, the master sergeant pulled it back, accepting instead a final assignment to lead a team of relatively inexperienced PJs, as Pararescue specialists are known, from the 38th Rescue Squadron on an Afghanistan deployment.

On March 23, 2003, during a mission to retrieve two Afghan children from a remote village, the Air Force HH-60 he was on crashed in a pitch-black valley, killing Maltz and five others.

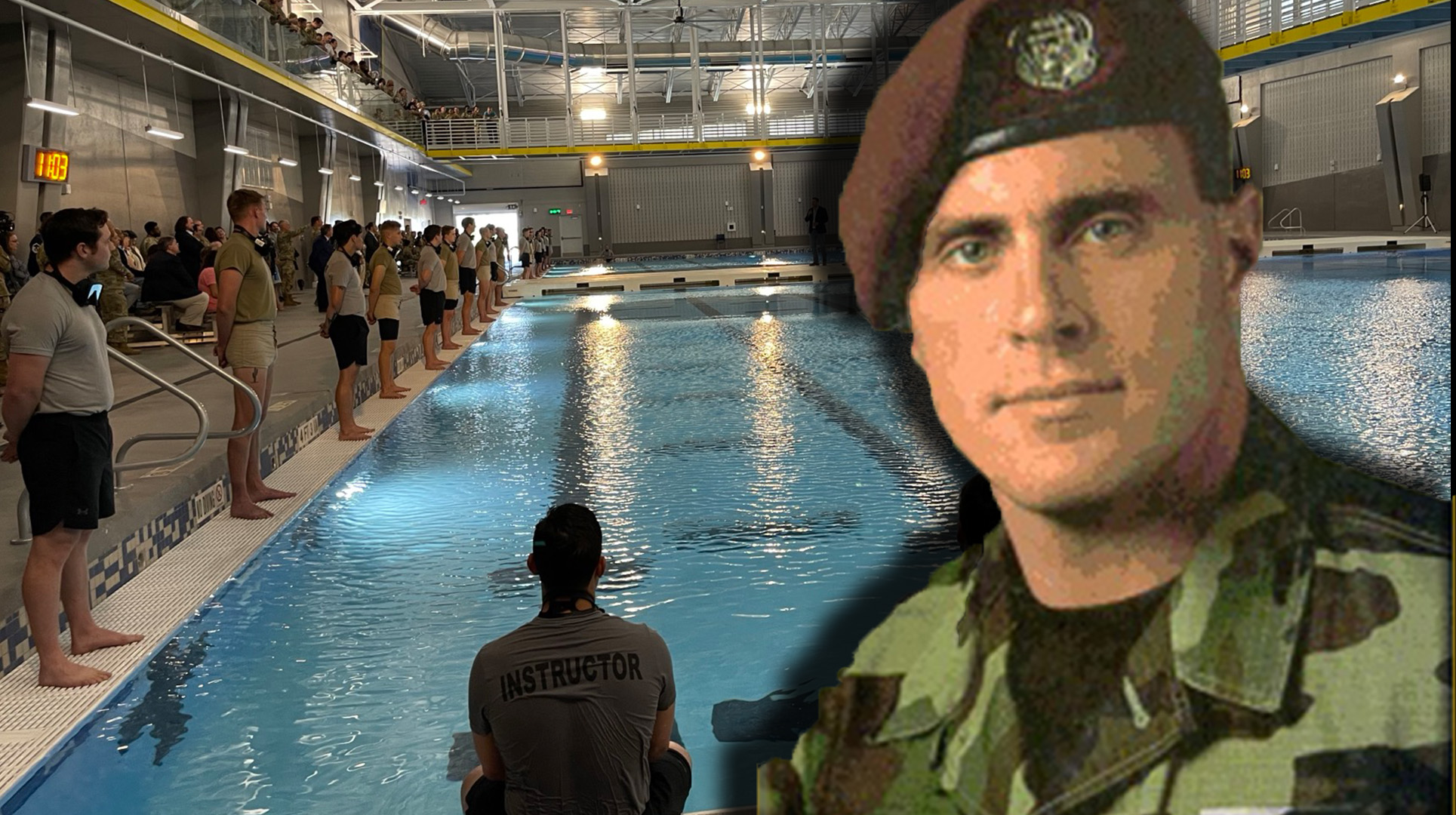

Tuesday, the Air Force christened the Maltz Special Warfare Aquatic Training Center, a $60 million, 76,000-square foot training hub at Joint Base San Antonion-Lackland. The complex houses 12-foot-deep Olympic-sized pools along with medical and therapy facilities, and will serve as a training hub for candidates seeking to join the Air Force Special Warfare fields of Pararescue, Combat Control, Tactical Air Control Party or TACP, and Special Reconnaissance.

Pool training has long been at the heart of Air Force Special Warfare selection courses, particularly pararescue and combat control. Students hoping to become PJs and CCTs spend hours each day testing their lung capacity — and mental strength — in a series of increasingly fiendish above- and underwater drills. Though students can swim miles in a day and tread water endlessly during pool training, it is the underwater drills that are most dreaded.

In exercises known as “water confidence” or “water con,” students swim underwater laps without surfacing, tie knots with ropes at the bottom of the pool and face so-called “drown proofing” drills, bobbing up and down from the bottom of the pool for a single breath with their hands and ankles tied together.

They also face “buddy breathing,” an underwater wrestling matching between two students sharing a single snorkle, and an instructor. The match has only two rules: students can only breath through the snorkle as they share it, and they can’t fight back as instructors pushes them under and twists them in circles.

For decades, Special Warfare airmen faced water con in a pool on Lackland that doubled as a community lap pool in off hours. With the opening of the Maltz center, officials say, the Air Force has a facility to match the training.

The face of pararescue

According to Rob Disney, a former Pararescue chief who knew Maltz well, naming the center after Maltz is a perfect tribute. To many PJs who joined the Air Force just before 9/11 or in the early years of the wars that followed, Maltz was literally the face of Pararescue — the New York native’s portrait was on the cover of a recruiting brochure used widely for much of the 1990s.

“When I first walked into the recruiting office, knowing nothing about Pararescue, I saw Mike on the cover of it,” Disney told Task & Purpose. “Before I even thought about being a PJ, my first thought of the job was him.”

Disney, who retired from the Air Force as a chief master sergeant in 2017, said Maltz was well-known among his generation of PJs from his fearsome reputation as an instructor at the school’s selection course in the mid-1990s. Though the school historically could weed out up to 90% of candidates (a rate that has improved in recent years), those who survived a Maltz-era class held it as a particular point of pride. Students who did tell stories of Maltz throwing mattresses out of windows during dorm inspections and rappeling from the roof of dorms to surprise — and punish — students who thought they had escaped his gaze.

Class cartoonists — a tradition in Special Warfare training — regularly drew scenes of an enraged Maltz pushing students through pool workouts and PT ‘smoke sessions.’

Disney arrived as a student just after Maltz had left.

“I heard about him, of course,” Disney said. “And I saw the cartoons the earlier classes left behind, and you think, ‘who is this crazy guy?’ So when I finally met him, I’m expecting this guy to be an axe murderer.”

In fact, said Disney, when he reported to his first assignment at Moody Air Force Base, he found Maltz was the most welcoming and friendly there — in his own way.

“On my first day, we went into the scheduling office where Maltz was, and I see him there,” Disney recalls. “He yells out with that New York accent, ‘you Disney? I think your name is pretty goofy.’ And then he laughs at his own joke.”

From that moment on, said Disney, Maltz was a warm friend. Born to a family with a tradition in law enforcement and fire fighting, Maltz was quick to banter and taunt — he took to addressing Disney as “Bobby,” a name Disney has never gone by — but eager to pass on his decades of knowledge and experience to a new generation. Unlike many senior NCOs, Disney said, Maltz relished challenging younger PJs in top physical shape to keep up with his own manic workouts.

“He’d pull up his shirt all the time and say, ‘Hey, Bobby, you ever seen abs like this on a 40-year-old man?'” Disney remembered.

As a field operator, some of Maltz’s rescue missions still ring in Air Force rescue lore. On a mountaineering trip in Alaska in the early 1990s, he led a team that reached the summit of Denali, then while descending came across two German climbers who had fallen ill. The men were at 20,000 feet, literally a mile above any hope of help, suffering from severe hypothermia and cerebral edema— a death sentence under normal conditions. Maltz tied one of the climbers to his own harness and walked the men down the mountain, a rescue credited as the then-highest ever recorded in North America.

Maltz also was one of the U.S. military’s premier freefall jumpmasters, helping develop Pararescue ocean jump procedures still used today.

The same intensity he brought to terrorizing students, Disney said, made him an exceptional leader. He knew every regulation and demanded every member of his team know them too, along with tiny details most missed. On one deployment, Disney said, Maltz told his young assistant team leader to unlock the team’s rifles from a storage rack, which was secured with a 4-digit padlock. When Maltz checked the padlock and found that the younger man had left the lock’s dials in place, revealing the unlock code, Maltz gave the younger PJ a memorably vulgar chewing out.

“With a PJ team, he was extremely meticulous about organization,” Disney said. “Whether organizing an equipment bay, or a deployment schedule, everything had to be in its place. He had a little saying, and he was so friendly with people he’d even introduce himself to strangers with it: ‘Hi, I’m Mike Maltz, I’m a pararescueman, we’re in town putting apples with apples and oranges with oranges.'”

Komodo 11

In 2003, Maltz considered retiring, even putting in for formal retirement orders, but changed his mind for a chance to lead a team in combat. Assigned to rescue helicopters in Kandahar that flew under the callsign “Komodo,” Maltz partnered with Senior Airman Jason Plite, a new PJ who at 21 was half Maltz’s age. On March 23, 2003, Maltz and Plite launched onboard Komodo 11 to retrieve two Afghan children who needed to be evacuated from a clinic.

Disney, by coincidence, was also on the mission, as part of a jump team on the HC-130 tanker assigned to refuel Komodo 11 as it flew. The night, Disney said, was so dark that even with night vision equipment, it was nearly impossible to see the surrounding terrain. As Komodo 11 attempted to join up with the tanker to refuel, Disney remembers, it abruptly dove away and, within seconds, impacted. The crash killed Maltz, Plite, Lt. Col. John Stein, 1st Lt. Tamara Archuleta, Staff Sgt. John Teal and Staff Sgt. Jason Hicks.

“He was the most committed, dedicated, and skilled PJ I ever knew,” said Disney.

The new training facility is not the first memorial to the Komodo 11 PJs.

Plite’s mother, Dawn, has run a foundation in his name since 2003, awarding close to $200,000 in scholarships to almost 70 seniors at Grand Ledge High School in Michigan, Plite’s alma mater. The fund splits the scholarships between students focused on sports and others focused on arts, both of which Plite embraced in high school.

For the last 15 years, Maltz’s brother, Derek, a career DEA agent, has coordinated an annual memorial workout dubbed the Maltz Challenge, each year dedicated to a list of fallen military members. Special operations units, law enforcement agencies and NFL teams all regularly participate.

But even after a career as a PJ — among the military’s most driven and Type-A personalities — Disney still has trouble expressing the sheer force of Maltz’s personality. He recalled a deployment to Kuwait, pre-9/11, when he and the rest of the team were asleep in tents. But from the team’s common room, he could hear vacuuming — a hopeless task in the desert, but one Maltz had assigned himself to fight insomnia.

Trying to sleep, Disney heard the flap to his tent open, then sensed the figure of Maltz hovering over him.

“Bobby,” Maltz whispered. “You asleep? You sleepin’ Bobby?”

It was, said Disney, close to 3 a.m. Other than Maltz, everyone was asleep, and Disney said so.

In a mocking voice, Maltz shot back in the darkness: “You lazy motherf***er. I guess they don’t make’em like they used to.”

The latest on Task & Purpose

- Air Force special operators must take class before getting shaving waivers

- Camp Pendleton Marines encouraged to fix their own barracks rooms

- 101st Airborne soldiers are first to receive new Next Gen Squad Weapon

- Air Force fires commander of Holloman maintenance group

- Army investigating Nazi imagery on Special Forces patch posted online