Navy junior safety Giuseppe Sessi understands the allure of the new, lucrative world of college football. He has former teammates and friends from his high school playing days in Texas, he says, who are cashing in.

One former teammate “was at UConn and then went to North Carolina with Coach [Bill] Belichick, and he was getting paid handsomely,” Sessi said this week. “One of my buddies is a walk-on at a Big 12 school. He gets paid a decent amount. I’m happy for him, but at the same time it’s like, ‘dang I wish we could get that too!’”

Sessi lets out a good-natured laugh at that last comment. Uniquely among high-level Division I football programs, the three military service academies do not allow players like Sessi to be paid as varsity athletes.

“It is nice for those guys,” he says. “When you’re on the outside looking in, you see other people making however much money, but something we talk about here is, you will be in a better place, you know, 10, 15 years down the road, than you would be at another place making some quick cash.”

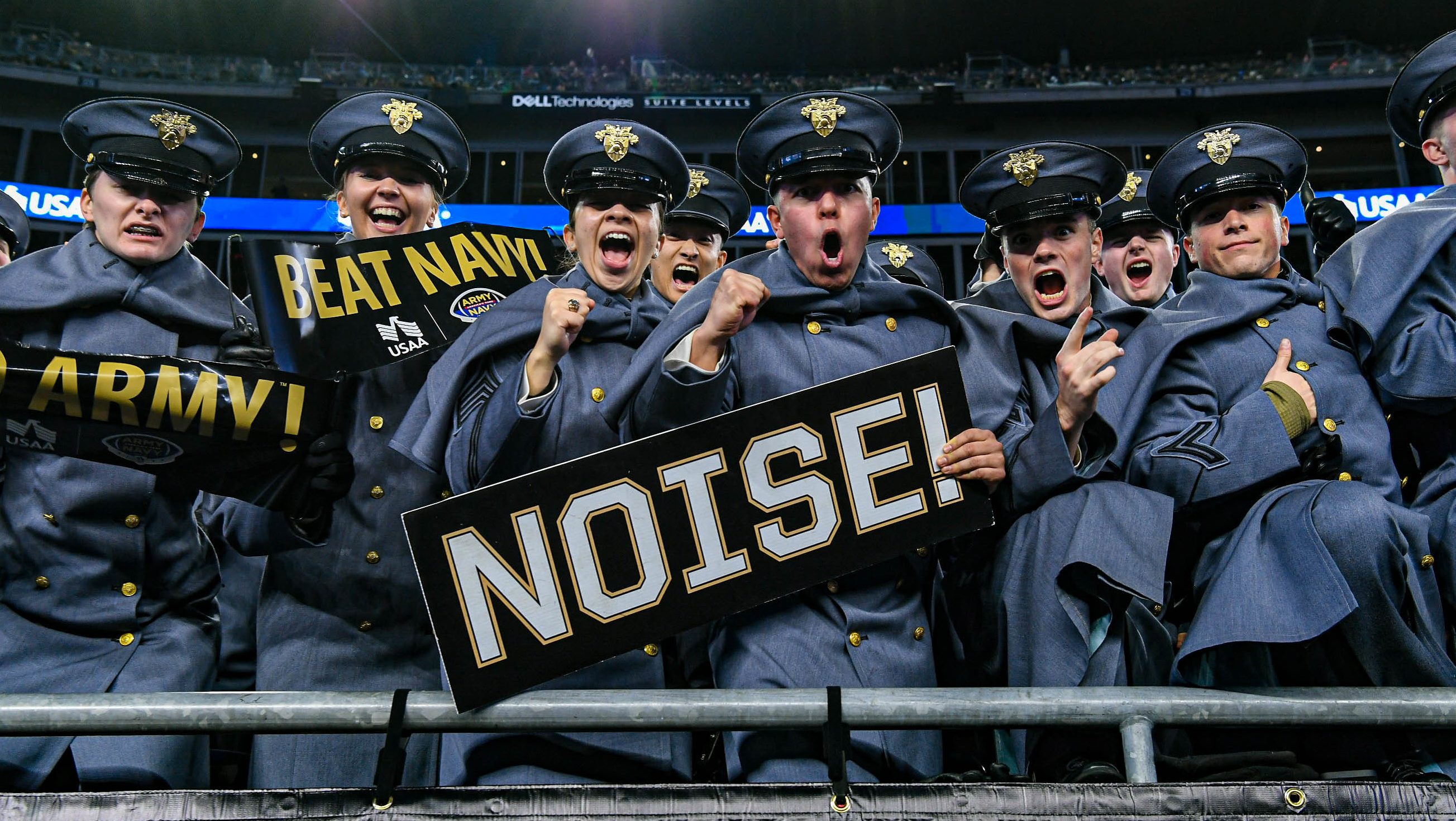

Sessi and his Navy teammates play Army this Saturday in their annual rivalry game in Baltimore. Sessi and upperclassmen on both rosters share a unique spot in the rivalry’s history, as the first classes to turn down a chance for big paydays to play for Army and Navy. In just the span of their college careers, football and college sports generally have been wholly transformed, from modest opportunities to earn a scholarship into high-dollar jobs.

In the course of a season, service academy players will line up against at least a handful of players earning close to, or perhaps even over, a million dollars. Even most of the typical starters and back-ups that cadets and midshipmen have squared off against collect yearly incomes that likely average at least $50,000, according to recruiting experts.

When the wave of changes began in 2021, many believed pay-to-play rules would ruin Navy, Army and Air Force recruiting efforts as top players would skip academy life for lucrative offers at traditional colleges.

But four years into the new era, the opposite seems to be true.

The last two seasons have included some of the strongest in either school’s history. In 2024, Army was ranked among the nation’s top teams at 12-2, while Navy was 10-3. This year, Navy is 9-2 with two games left.

Top Stories This Week

And players on both teams are collecting awards not seen on either campus in decades. Army offensive linemen Lucas Scott and Paolo Gennarelli were both named All-Americans in 2024, and on Wednesday, Navy nose tackle Landon Robinson was named a 1st team All-American by USA Today and Sports Illustrated.

“When all this was starting to come about, people were saying the academies weren’t ever going to have a competitive team again,” said Navy quarterback Blake Horvath, who, as a 2022 high school graduate, was in the first class of players whose recruitment offers could include cash. “We’ve taken a negative and turned it into our strength.”

Army coach Jeff Monken said the schools have succeeded by choosing not to adapt to the new rules.

“When they make a commitment here, they are committed to becoming Army officers, and they can’t have jobs doing other things,” Monken said on the Next Up with Adam Breneman podcast last summer. “I think that what every American citizen can be sure of is that our young men and women who come here are committed to one thing, and that’s serving their nation with distinction and honor.”

Passing up big dollars

Beginning in 2021 — just as current Army and Navy juniors and seniors were being recruited — a series of lawsuits and settlements essentially reinvented college sports, ending the prohibition on players being paid and lifting restrictions on players transferring between schools.

Transfer rules now allow players to leave one school and enroll in another with no penalty in eligibility. The impact of the change has been seismic: In 2021, fewer than 800 football players transferred between schools, according to On3, a major college football tracking site.

So far in 2025, over 4,000 players have said they are considering moving.

The military academies do not accept mid-career transfer students.

But the extinction-level event across college sports has been the arrival of money. And not just some money, but previously unimaginable amounts of money, at many of the 60-odd campuses in the top four football conferences, which are known as the Power Four or P4 leagues.

The biggest stars at top P4 schools like the University of Texas or Georgia or Miami make millions of dollars a year (Texas quarterback Arch Manning is believed to take in $5.3 million). But even average starters on less glamorous P4 teams, like Maryland or Virginia Tech, can count on at least $100,000 per year, according to Brian Dohn, a national recruiting analyst at 247Sports.

“A three-star recruit going to Power Four teams like Maryland, Rutgers, Virginia Tech out of high school, a lot of them are getting six figures,” Dohn said.

Below the Power Four schools are five more leagues, commonly called the Group of Five, or G5 schools. All three academies play in G5 leagues, Navy and Army in the American Athletic Conference, Air Force in the Mountain West.

At most G5 schools, Dohn said, good players can expect to make between $50,000 and $100,000, though maybe not right away.

“Most [G5] places aren’t paying kids until they’re on the two-deep,” Dohn said, referring to the depth chart a team maintains of its starters and 2nd-team back-ups. “It’s not an astronomical amount. It’s maybe low five figures. They’re gonna pay their kid after they do something.”

But rather than losing top prospects to big paychecks, the transfer rules and big paydays have actually created better conditions for service academies to recruit by reducing competition for high school players, according to Navy coach Brian Newberry.

“Four years ago, we may be recruiting a kid early on that might have 20 offers” of a scholarship, Newberry said. “That same kid may have half or less than that now. And so maybe a kid that had a lot going on in the past that maybe wouldn’t consider the Naval Academy before, maybe they consider us.”

One factor helping service academy recruiters is the ever-higher price of recruiting top high school players, which forces traditional schools to conserve funds by making fewer scholarship offers to players lower in the pecking order.

But the main driver in the teams’ favor is transfers, as elite players who initially choose a top-tier school realize they will not see much playing time. Those players now decide to transfer when they likely never would have under old rules.

“If you think every school maybe takes three or four less kids, now we’re talking 60 schools, and now we’re talking 180 to 200 less kids,” said Dohn. “That means the [traditional G5 teams] can take some of those kids [as transfers]. So then maybe the lower level [high school] kid doesn’t have as much of an option.”

Not a payday but a commitment

In the end, Dohn said, Army, Navy and Air Force are still finding the same players they always have.

“You gotta be a special kid to go to Army or Navy, and I don’t just mean they have to be really smart, they have to be of high character, because there’s kids like that in all programs,” Dohn said. “But you also have to embrace the military lifestyle, understand what that lifestyle is while you’re in school, and really have a long-term outlook.”

“Not a lot has changed here for us,” said Army’s Monken. “Our guys don’t come here for money. They come here for West Point. They come here for this education and the opportunities that they’ll have following graduation, to serve as a United States military officer.”

Army team captain Kalib Fortner is a senior, and Saturday’s game will be his final chance to beat his school’s biggest rival. Like Navy’s Horvath, he has watched the waves of change wash across the sport with a sense of detachment.

“Academies are kinda the last brotherhood in college sports,” he said this week. “Everybody’s not playing for a dollar bill. They’re playing for the love they have for one another in that locker room. To play for a great institution where academics mean more and life outside football means more.”