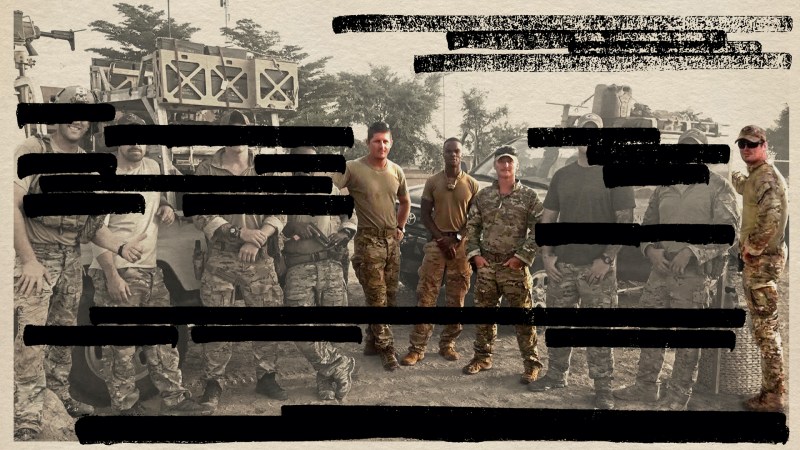

The film jumps around, seemingly without structure. At times Marines are patrolling, other times they are sitting against walls, smoking, waiting. There are brief moments of combat, and then down moments of boredom.

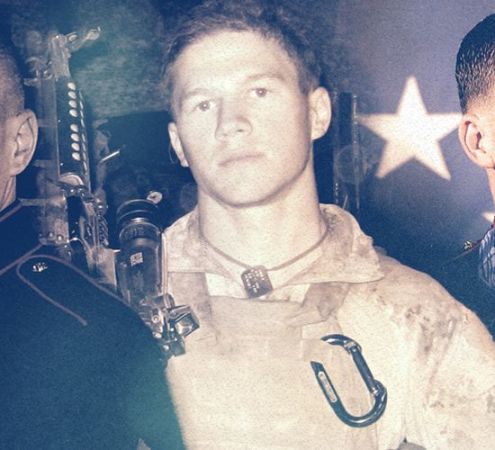

Titled Combat Obscura, it offers no timeline to follow, and gives little thought to the strategic outlook of the Afghan War, which was just a quaint nine years old in 2011 when footage was first shot by Marine Lance Cpl. Miles Lagoze, then a 21-year-old combat cameraman attached to 1st Battalion, 6th Marines.

Yet it gives perhaps the most raw and realistic look at what an infantry Marine sees while on a combat deployment overseas.

It looks nothing like the recruiting pitch being sold to American teenagers, which is probably why the Marine Corps itself wanted nothing to do with it.

“The actions depicted in the film of these few betrayed the trust and safety of their fellow Marines; they selfishly put their own self-interests over their unit, and by doing so put their entire team at risk,” said Maj. Brian Block, a Marine Corps spokesman.

Although the Corps previously threatened legal action against the Marine veteran — since he used government-issued equipment to capture much of it — Block now says Lagoze is in the clear.

“While we contend that at least some of the content of the film — produced with Marine Corps equipment, during a Marine Corps deployment, and not cleared for public release by any official release authority — is rightly the property of the U.S. Government, we do not plan to pursue any legal action against Mr. Lagoze at this time,” said Block.

“That definitely is a weight off,” Lagoze told Task & Purpose, which first informed him the legal threat from Marine officials had been dropped on Thursday.

Combat Obscura

For more than a year, Lagoze had the threat looming over his head after his film premiered on the festival circuit. Obscura received even more attention from Marines young and old after Task & Purpose’s James Clark offered a review. The reason why the Corps was so pissed at the hour-long documentary could perhaps be found within the opening moments of the film, as grunts wait for an airstrike on a compound.

“Bout to have a drop right here, yeahhh!” one Marine says, as a camera focuses on an Afghan compound. Then seconds later, a blast is heard, and the camera turns to a house hundreds of meters away. “Holy shit. That’s the wrong building. Holy shit! Yeah boy!”

It’s just one of many scenes that upend the spit and polished image the Marine Corps wants to convey to outsiders. But as most Marines know (including this writer), the reality is much more than dress blues, marching in formation, and love of country.

“We knew it was kinda bullshit when we were out there. We knew we weren’t making that much of a difference,” Lagoze said.

Among the scenes you definitely won’t find airing on AFN are Marines packing their own cigarettes with hash or others smoking marijuana while pulling security at their patrol base — most notably, a grunt fashions a bong out of an empty Pringles can. There are Marines being wounded and evacuated. Another scene shows Marines aiming their weapons at an unarmed Afghan man, who is made to strip naked in order to be checked for weapons. Naturally, the scene is cut right after a Marine says in an interview ready-made for public affairs release that their mission was to “build relationships with the locals.”

Combat Obscura

“There’s been so many fake depictions of the war, that it’s worse not to show what it was actually like,” said Lagoze. “People are really sick of the hero worship and stuff like that. [These Marines] were in a fucked up situation. This is more real.”

As a videographer for the Marine Corps, Lagoze’s job was to accompany the grunts out on patrol and back at base, interviewing them and shooting footage of what they were doing on a daily basis. But what they were really doing was not what the brass wanted to see.

He was told to film the “hearts and minds stuff of the war” — handing out candy to Afghan children, grunts patrolling with the Afghan Army, and interviews with Marines that could be released to the public showing they believed in the mission and were happy with what they were doing — all of which is standard fare that is uploaded daily to the Defense Department’s imagery portal.

But he was given limits: Don’t capture footage with grunts smoking or using profanity — which is almost a prerequisite to being an infantryman. No casualties. And whatever you do, don’t shoot videos of anyone without their full gear on. “That was actually a big one,” Lagoze said. “If they were running around without their helmets on, their proper protective equipment, someone was gonna flip out.”

In one instance, Lagoze said, there were videos that ended up being released that “got a lot of flak” from higher-ups because some of the infantrymen were seen during a firefight wearing only green t-shirts underneath their body armor. Others were only in flip-flops.

You can imagine the theoretical ass chewing to come later: In combat, gentlemen, you will be fully dressed before returning fire to the enemy.

But as Lagoze states in the opening moments of the film with text appearing on screen, a rare moment of narration, “we filmed what they wanted, but then we kept shooting.”

The Corps took issue with Lagoze retaining footage he and others shot while overseas that was used to make the film, which Block said could “set an unfortunate precedent.” He went on to say that Marines on deployment should be focused on their mission, and not their “personal ambitions” — in other words, not going into the Marine Corps and gaining unfettered access to its personnel, solely for their personal benefit later.

But Lagoze rejected that line of reasoning, telling Task & Purpose that he never thought about making a documentary until he had entered film school and started looking back through his old footage. He also brought up the mission of combat camera, which is to produce imagery for public consumption and to document for historical purposes.

“I can only film what’s happening around me. If they’re looking for only certain things that fit into that historical documentation, then I see that as problematic,” he said, adding: “I was providing an outlet so that these guys’ stories wouldn’t get lost and whitewashed in the sanitized version the Marine Corps wanted to perpetuate. It wasn’t personal ambition.”

As for the alleged criminal activity depicted in the film — Marines taking drugs, for example — the statute of limitations has long since passed. And Block stressed that the film does not represent the “experience or attitudes of the vast majority of Marines who deployed and served with honor and distinction in Afghanistan.”

But it does provide a snippet, a brief moment in time, when there was still hope for a “win” in Afghanistan. It gives a window into the fucked-up and un-sanitized world of the Marine infantry in combat, where a grunt’s sanity is often tested by the thought that the next step could be their last.

This fear, usually unspoken among men whose leaders sometimes call them modern-day Spartans, is best captured in the film when one Marine is interviewed just moments after a Taliban attack on their compound. His head bandaged after taking shrapnel, which he initially brushes off as a “boo boo,” and with one Marine being taken away for medical evacuation in a helicopter, the facade of toughness finally breaks down: “I don’t, uh. I don’t want any more combat. I think I’m good after this.”

“You’re ready to go home, aren’t you?”

“Yeah.”

“I’m scared. I’m fine now, but when it was happening, it was like, fuck, I never thought they’d get that close. I never thought they’d hit us in the compound.”

More broadly, Combat Obscura gives people a look at the real-world consequences that can be wrought by generals who believe that “muddling along” in Afghanistan is a viable strategy. And that, at least, has to be worth something.

Combat Obscura

“You can get your legs blown off or your head blown off at any moment,” said Lagoze, a Purple Heart recipient. “It’s a little unrealistic to expect 19-year-old kids to be these perfect soldiers, these perfect human beings, especially in as fucked up a situation as Afghanistan.”

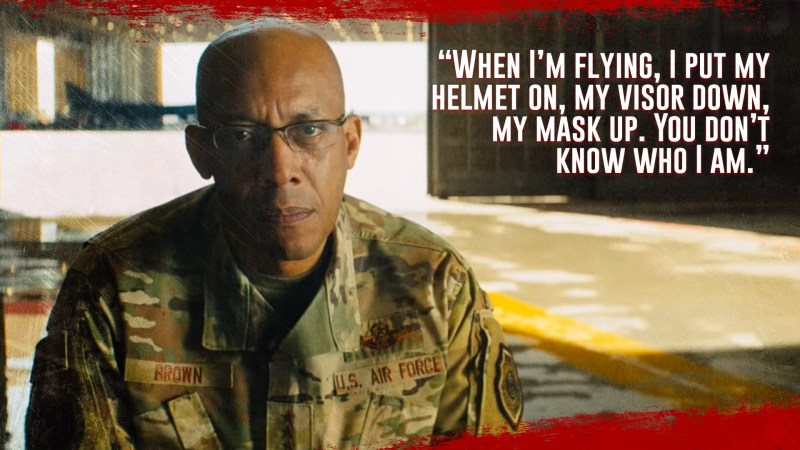

“You can shit on the guys on the ground out there, but who’s running the war? Who thought what we were actually doing was going to work? That’s what I think we should be more focused on than kids smoking hash.”

The film hits theaters on March 15.