Joe Hardebeck remembers the bullet coming so close that it burned the side of his face.

Standing next to a mud wall on Feb. 21, 2010, a little over a week into the Battle of Marjah, the Navy corpsman was scanning for insurgents through his rifle scope as two squads of Marine infantrymen patrolled toward Taliban lines during what was then the largest joint operation of the War in Afghanistan. Moments later, a shot from a Taliban fighter passed dangerously close to his cheek and struck the wall next to him so hard that his eardrum was blown out. “They were very close,” Hardebeck told Task & Purpose last week, recalling that he instinctively turned his head away as debris pelted him.

“I think they’re shooting at me,” remembered Hardebeck, then a hospital man third class.

Marine Capt. Ryan Sparks, his commanding officer, agreed. “Get the fuck down,” he recalled Sparks saying.

Now bleeding from his eardrums, the deafened 22-year-old sailor had someone quickly check him out. Hardebeck couldn’t hear much, but he reasoned he was still in the fight and could still help save wounded Marines. And there was little time for reflection. He and several Marines of Bravo Company, 1st Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment had to keep moving and get across a road to avoid heavy enemy machine-gun fire.

Hardebeck also knew his small team of military medical professionals had treated Marines during the battle who had suffered far worse injuries from improvised explosive devices, gunshot wounds, and shrapnel. At the end of the first day of fighting, which began on Feb. 13, Hardebeck had treated two wounded Marines, and by the time he too was wounded, eight Americans and three British troops had died.

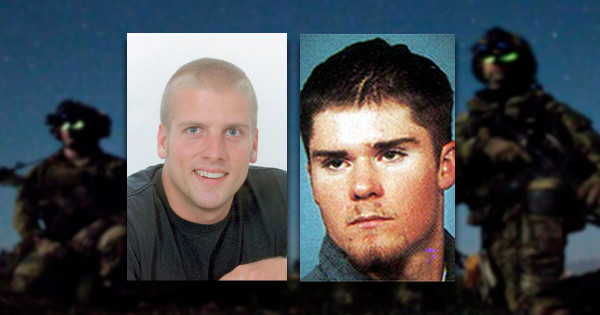

Responding to frantic calls of “corpsman up!” Hardebeck had been repeatedly sprinting around Marjah, the main Taliban stronghold in Helmand Province, for more than a week trying to save people’s lives. On the afternoon of the first day of the battle, Cpl. Jacob Turbett, a Marine engineer, was shot by an enemy sniper right in front of him. “I watched it happen,” Hardebeck said. “I was the first one to him.” Turbett died minutes later.

As the battle to drive militants from the Taliban stronghold of Marjah raged on in those initial days, there was little time for Hardebeck to think about much else beyond the constant enemy fire. “There was no single shot, and there was no single firefight, it all just collapsed and compressed into one composite shit storm,” James Clark, now deputy editor of Task & Purpose, wrote in 2015, recalling his experience as a public affairs Marine alongside Bravo Company during the operation.

“During those first three days, more than once I recall being stuck in some wide-open field as enemy rounds flew overhead; some close, some not, all the while wondering why the fuck I left the cover of a nearby mud wall,” Clark wrote. “A rocket-propelled grenade flew into one of the compounds we were holed up in, bounced off the ground, slammed into a doorway and skidded to a halt, feet away without detonating. One night, a large underground propane tank ignited and sent up a pillar of flame 20 feet in the sky, looming over us.”

“Many of us had so many close calls,” Hardebeck told Task & Purpose. “It was just another day in Marjah.”

Indeed, the same day that Hardebeck was injured, he had another close call soon after when Sparks and the company first sergeant reported that another Marine had been hit. The fastest way to get to him was across a wide-open field with mud-walled compounds on both sides. “A perfect funnel of fire,” Hardebeck recalled.

They took turns sprinting towards the wounded Marine — reciting the infantryman’s mantra for running under fire of “I’m up, he sees me, I’m down” — and found the Marine had been shot in the helmet and had a fractured skull. Fortunately, he was medically evacuated and survived.

Later that evening, the fighting had died down and Hardebeck was examined by the Navy doctor leading his trauma team. Although a light rain had washed away the blood, Hardebeck recalled the doctor treating him saying he had “obliterated” his eardrum. Two more witnesses reported Hardebeck was in pain from a burn that was swelling on his right cheek. “He also mentioned that his ear hurt him a lot,” Marine Sgt. Andrew Danecki wrote in a sworn witness statement dated Jan. 8, 2016. “From the sound of the round and that his cheek was really sore and stinging, that he was trying not to touch it.”

“As we were talking, he expressed how he had just recently, minutes before, almost had his head blown off by enemy fire,” recalled Jason Boykin, a Navy religious program specialist, in a sworn witness statement dated June 8, 2015. “When looking at his face, he sure enough had a burn on his right cheek on the outer portion of his face, it was red and inflamed and just barely bleeding.”

But Hardebeck didn’t want to leave his Marines, and fortunately, his hearing mostly came back a few days later. It didn’t dawn on him that he had been wounded by enemy fire and given medical treatment on the battlefield, earning him the Purple Heart. “I never wanted to push anything,” he said. “I came back with all my digits.”

But after more than 11 years, the 33-year-old petty officer second class finally received the Purple Heart award during a ceremony on July 1 in Camp Pendleton, California. With the U.S. pullout from Afghanistan essentially “over,” he is one of the last American service members to receive the award for wounds received during America’s longest war.

“As the war in Afghanistan draws to a close this September, it is a timely reminder of the sacrifice and commitment to duty our Operation Enduring Freedom veterans demonstrated,” said 1st Lt. Kyle McGuire, a spokesman for the 1st Marine Division. “While that conflict ends, these veterans remain in our communities and continue to impact our Corps.”

‘I would have rather stayed out there and treated those guys’

The oldest U.S. military award still given to American service members, the Purple Heart was first created as the Badge of Military Merit by President George Washington in 1782 and given to soldiers who displayed “not only instances of unusual gallantry in battle, but also extraordinary fidelity and essential service in any way.”

In today’s era, any service member who is wounded or killed by enemy action is eligible for the medal. But Hardebeck, who is among the roughly 20,500 American service members wounded in the War in Afghanistan, didn’t have it documented during the battle and never reported it afterward.

“I would have rather stayed out there and treated those guys,” said Hardebeck, who estimated that he treated roughly 40 patients — Americans and Afghans alike — during the battle who were injured by gunshot wounds, blasts, and burns. The Indiana native explained that he would have felt out of place wearing an award for a round that thankfully missed his head when insurgents were filling pressure cookers with marbles, screws, and ball bearings to inflict shrapnel on unsuspecting Marines. “It just shreds people’s bodies,” Hardebeck said.

That changed in 2017 when many of the men of Bravo Company reunited at a funeral for one of their own. They drank and ate together, talked about what they were doing now, and reminisced about war. “Life was so simple over there,” Hardebeck said. “All you worried about was life and death decisions.”

Eventually, they started talking about close calls. And when Hardebeck shared his, he recalled Marines urging him to look into it since they believed he rated the award. “Half of them rated it but none thought about it.” But they agreed he would try and get what he was due.

“I’ve accepted the fact that I rate the award,” Hardebeck told Task & Purpose. “I pursued the award because I gave my word.”

Hardebeck gathered the necessary evidence for the award and received endorsements from his commander at the time, and according to a Marine official, after a “long administrative process,” Hardebeck was approved for the Purple Heart on April 6, 2021 with the signature of Lt. Gen. Carl Mundy of Marine Forces Central Command.

‘He’s not your average HM2’

More than a decade after the battle that inspired international headlines, documentaries, and stamped a few thousand grunts with a label revered around the Corps as “Marjah Marines,” Hardebeck continues to serve alongside Marines, although he’s now among just a handful in his unit who have seen action in Afghanistan since the last combat unit left in 2014.

“I hit the jackpot,” Capt. Ulysses Sosa, commander of the Alpha Battery, 1st Battalion, 11th Marine Regiment said he recalled thinking when he first met Hardebeck during training for the Marine artillery unit in Twentynine Palms, California. The corpsman has seen more than most, but remains humble and often shares his experiences in Afghanistan and shares the “why” that underlies training for combat, he said.

“He’s not your average HM2 [Hospitalman 2nd Class],” said Sosa. “Doc is definitely one of those guys who improve the cohesion of the unit.”

“Don’t think for a moment you’re so young you can’t be in combat,” Hardebeck remembers telling the artillery Marines who are, according to Sosa, slated to deploy with the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit sometime next year.

And now that has had time to reflect on Marjah and how it made him who he is today, Hardebeck said, he fondly remembers those on his left and right back then, even as he continues to press on after more than a decade in the Navy.

When he thinks back to that battle, Hardebeck’s words convey a difficult truth, one that was hard-learned, and harder still to accept, but it’s one that many combat veterans, like him, know all too well: You do what you can — all that you can — and that is all that can be asked of you.

Hardebeck did all he could for his Marines. He raced to them when they needed him most, across fields crisscrossed by incoming fire, and down a maze of alleyways. He risked his life for theirs. And he bled for his Marines. Now, finally, he has been rightfully recognized for all that he did.

“I don’t regret any of it,” Hardebeck said of his time in Marjah, despite not being able to save everyone. “In those moments I knew I did everything I could possibly do for them.”