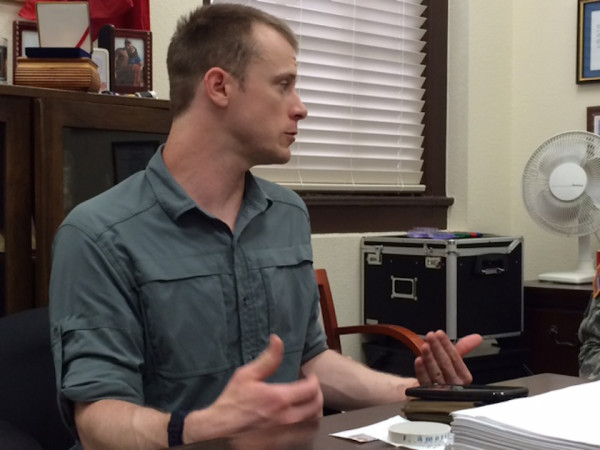

On the day he was served with charges of desertion and misbehavior before the enemy, Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl’s defense team released a statement to the media saying that since the government was releasing information about the charges, the defense team was releasing a 13-page letter they had delivered to Gen. Mark A. Milley, the commanding general of U.S. Army Forces Command, on Mar. 2, 2015.

Although the defense team couches the letter in terms of attempting to persuade Milley into delaying a disposition decision in Bergdahl’s case, the letter reads much more like a mitigation case one would see during the sentencing phase of a court-martial. In so doing, Bergdahl’s defense team has essentially revealed its hand up front and put all its cards on the table, well ahead of the Article 32 preliminary hearing in the case. It is an extraordinary step and a gamble with two equally possible results: It could generate public sympathy and pressure for the Army to deal with the case at some lesser forum, which would benefit Bergdahl by disposing of the case less punitively and more quietly; or it could serve to provide the prosecution with ample time before trial to rebut every allegation Bergdahl makes. But it also overlooks one fundamental fact: Nothing in the letter is relevant to whether Bergdahl is guilty or not guilty of desertion and misbehavior before the enemy. In doing so, the defense team has put the cart before the horse.

The letter starts off with a discussion of Bergdahl’s poor health situation. It thanks the people who worked to get him released. It states that Bergdahl has cooperated with federal investigators in their efforts to “identify, capture and bring to justice the Taliban fighters who captured him and with great cruelty held him against his will for nearly five years.” The letter claims that Bergdahl “did not act out of a bad motive,” “did not intend to remain away from the Army permanently,” that there is “no evidence that any Soldier died searching for him,” and that there is “no evidence of misbehavior of any kind while he was held captive.” The letter even includes as attachments some of Bergdahl’s commendatory material, including personal awards and good performance reports.

But the specter that hovers throughout the defense’s submission is the claim that Bergdahl was tortured while in captivity. These claims have received widespread media scrutiny, and the defense supports this claim by including a typed, two-page, single-spaced statement prepared by Bergdahl, that alleges, among other things, that he was chained to a bed for three months after he attempted to escape, suffered significant physical injuries and illnesses, was caged and kept in constant isolation for the duration of his captivity, repeatedly told he was going to be executed, repeatedly threatened with torture, beaten, starved, and attempted to escape approximately 12 times. The letter is unsigned and undated. It paints a very ugly picture, and anyone, regardless of their position on Bergdahl’s case, should be outraged by his alleged treatment.

This alleged abuse may all very well be true, but it’s not relevant until sentencing, and putting it out there so early in the trial process looks very familiar; the torture card has also been played by the Sept. 11 and USS Cole bombing defendants in the neverending run-up to their military commission trials. However, this has always begged the question: Even if they were coerced or tortured, what does that — having happened after their capture — have to do with whether they are guilty or not of committing their alleged offenses before they were captured? The answer is nothing, but the tactic is designed to prevent the case from ever getting to a trial on the merits of the charges. Perhaps Bergdahl’s defense team is hoping for a similar result in his case.

While the letter claims that the defense wants to avoid litigating the matter publicly, by releasing it to the media for public consumption, it does just that. Nearly every one of the subjects is typical evidence the defense puts forward during the sentencing phase of a court martial in an attempt to obtain a lesser sentence. Things like the accused’s health or mental condition, any cooperation with investigators, and his “good military character” as evidenced by his awards and performance reports, are all fair game during the sentencing phase of a case. Harsh confinement or detention conditions are also fair game, if they exist. Except in very limited circumstances, such as good performance of military duties, these circumstances are not relevant or admissible during the guilt phase of a trial.

As the defense team’s Mar. 25 statement requests, we should all continue to withhold judgment until the facts of the case emerge. Defense lawyers have an extremely difficult job, especially in high-profile cases like Bergdahl’s. It may be that they feel their only chance to obtain a fair result is to put their strategy on the table now and attempt to sway public opinion in Bergdahl’s favor. It’s a strategy that portrays Bergdahl as a misguided and naïve young soldier whose motives were righteous, and which focuses not on his alleged crimes, but all that allegedly befell him after he was captured. It’s an all-or-nothing approach.

It could work, if the government doesn’t have any evidence to prove otherwise. But the fact that the Army took several months to investigate Berghdahl’s case and still charged him with desertion — a crime that requires proof the accused intended to remain away from his unit permanently instead of the lesser offense of unauthorized absence, which does not require such intent — in a case that has received such widespread media attention and government involvement on Bergdahl’s behalf, seems to support the conclusion that the prosecution believes it can prove its case.