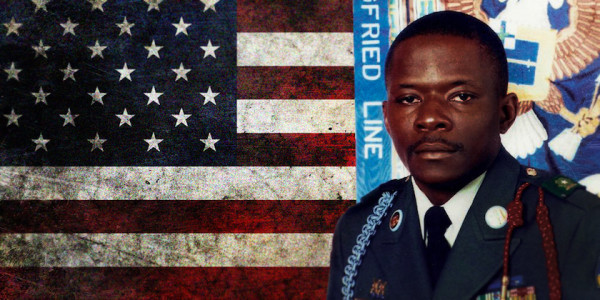

Army Master Sgt. Matthew Williams had other plans for his life.

He wanted to join the FBI, and he got a degree in criminal justice. He told Task & Purpose on Tuesday that he jokes that he “never grew up” from the little boy who wanted to be a policeman, or firefighter. But like countless other soldiers, his plans completely changed after September 11, 2001. The Boerne, Texas, native joined the Army in 2005, and went into Special Forces.

The beginning of Master Sgt. Williams’ story isn’t very remarkable — but the rest of it is something else entirely.

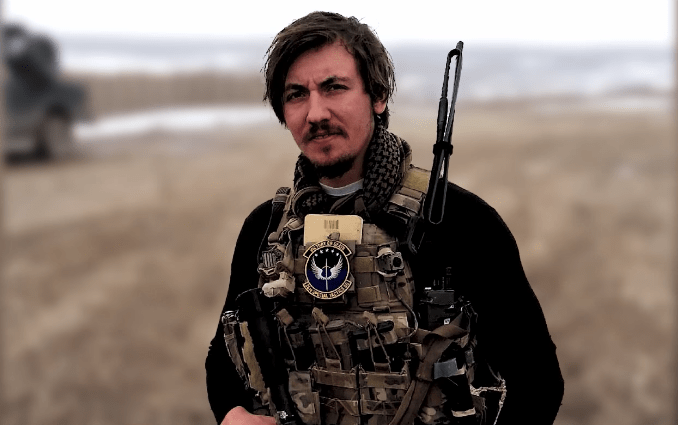

Williams is a weapons sergeant, and was serving with the Special Forces Operational Detachment Alpha (ODA) 3336, Special Operations Task Force-33 during his first deployment to Afghanistan. Williams was awarded the Silver Star along with nine other men for an almost-seven-hour firefight known as the Battle of Shok Valley. It was announced earlier this month that he would be having the Silver Star upgraded to the Medal of Honor, which he’ll receive on Wednesday.

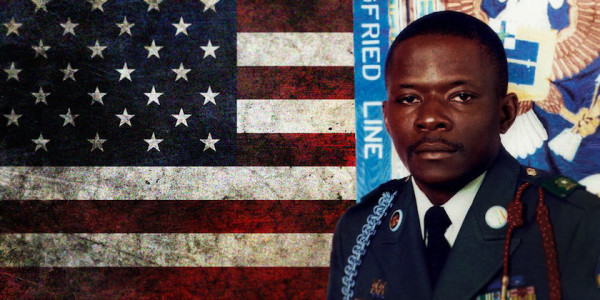

He’s the second soldier with the 3rd Special Forces Group (Airborne) to be awarded the Medal of Honor for this operation, joining Staff Sgt. Ronald Shurer II, who received the medal one year ago.

And after hearing how the battle unfolded, it’s no surprise so many awards came out of it.

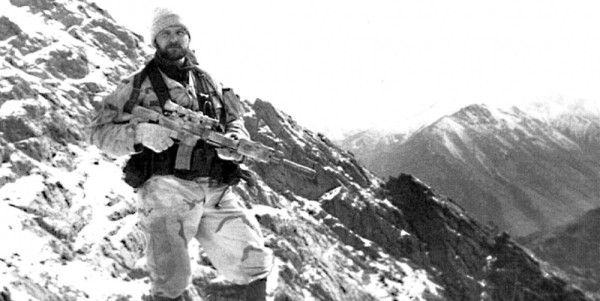

On April 6, 2008, ODA 3336 was up and ready to roll at two or three in the morning, getting ready for a mission to go after a high-value target in Shok Valley. The weather was shit — Lt. Col. Kyle Walton, the detachment’s commander, told reporters on Tuesday that it was snowing and that when they arrived at the mountain a little after daybreak, the helicopters weren’t able to land, meaning soldiers were jumping from helicopters into an ice-cold river, or onto jagged rocks.

Walton led his team of U.S. forces with Afghan commandos up the mountain — “zigzagging back and forth,” he told Task & Purpose. Within minutes, they began taking fire. One Afghan interpreter was immediately killed; many other forces were hit instantly. His group was “completely exposed” to the enemy, and the majority of the force was still at the base of the mountain.

The forces higher up the mountain spent the first half hour of the battle moving casualties out of the line of fire, and eventually were backed up “against a huge cliff” — measuring about a 100-foot drop. He radioed for backup, and medical assistance.

Back at the bottom of the mountain, Williams grabbed a group of commandos and began working their way up to reach the men who had been injured. While Americans devised a plan to get casualties out of harm’s way, the Afghans pushed back at the enemy.

Walton told Task & Purpose that the situation was “rapidly deteriorating … we were in a scenario where we were going to die right there and we were not going to leave our casualties. At one point, the option of everybody rolling off the side of the cliff was a real one.”

In the midst of the battle, Master Sgt. Scott Ford (Ret.), the team sergeant of ODA 3336, was shot in the arm — he told Task & Purpose that the bullet severed his humerus bone. He told Williams, who had been moving from one position to another “getting tasks done for the team,” that he would take himself down the mountainside, but Williams knew it wasn’t possible and helped him down himself.

Staff Sgt. Ron Shurer II, the team’s medic during the operation who also earned the Medal of Honor as a result of the battle, told Task & Purpose that the side of the mountain “was not the place to be if you cared at all about yourself.”

The pair continued taking fire, and Williams went back up after assisting Ford, learning that the route he’d just taken wasn’t a viable option in getting the guys who had been sustained leg injuries or other wounds that wouldn’t allow them to move quickly. They began making another evacuation plan.

Shurer said Williams was “moving around calmly, doing his thing,” which gave him a sense of comfort as he worked on casualties.

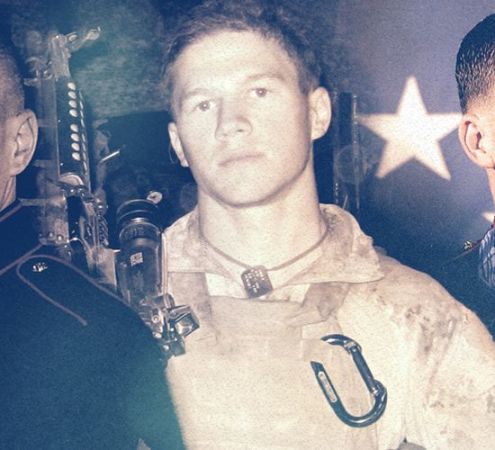

Army Sgt. Matthew Williams gets a photo with his operational detachment’s interpreter in Jalalabad, Afghanistan.Photo courtesy of Master Sgt. Matthew Williams

“If I had to describe his actions in one way it would be he was always looking for work,” Walton said of Williams. “So when Matt completed one task, he showed right back up, all of it under fire, all of it under extreme physical stress and enemy activity around us.”

At one point Walton said one of the three radios he was using went out, and Williams “magically appeared … fixed it, handed it back, and then went onto the next task.”

Williams said that while he wasn’t completely confident, he wasn’t allowing himself to dwell on the situation they’d found themselves in.

“At no one point did I ever sit there and say, ‘This is it, it’s over,'” Williams told reporters on Tuesday. “That type of thinking is not something that we do, it’s not something that we’re trained to do, and it’s frankly not something that gets you to the position that we were in, being Green Berets.”

All the while, air support was doing what they could to help the men on the ground – Walton said he’d never seen “the kind of acrobatics” pilots were performing.

“Whether it be the Air Force with A-10s or F-15s, or the Apaches from the Army or even the Black Hawks … everybody in all of those units, in the whole theater, as trying to support us,” Walton said. “They even launched a B-1 bomber out of Iraq to support our battle as well.”

He also said that more than 70 danger-close airstrikes were launched – meaning an airstrike that’s expected to wound or even kill the soldier calling it — one of which was “almost directly on top of” the team’s position.

The team started lowering casualties “almost straight down” the cliff they’d been backed up against. Walton said it was “problematic, to say the least,” but his instruction to the rest of the team was, “broken arms and legs are fine — can we get them down and will they survive?”

After getting the injured men to the base of the mountain, the partner forces continued taking heavy enemy fire, making it extremely difficult — nearly impossible — for medical evacuation aircraft to reach them and get them out. Pilots and crews were injured, but Walton said he’d never seen “the kind of amazing acrobatics…and some of the maneuvers that those pilots did.”

They were flying under power lines at full speed, he said, under heavy fire. But eventually, everyone was evacuated, and whisked out of harm’s way.

Williams told Task & Purpose that the first thought for all of them was about the injured men — where were they, how were they doing, what’s going on — but that eventually there was “a little bit of relief that it’s finally kind of over, you know, we finally made it back to our base.”

Shurer said when he was told he’d be receiving the Medal of Honor, he was “almost embarrassed” telling the other guys, because of the valor they exuded during the same operation. But Williams receiving it just seemed right.

“When I found out I was going to be receiving the Medal of Honor … a lot of it was confusing,” he told reporters. “I’m a medic, I was out there being the medic, doing my job. What else was I going to do that day? But when I found out that Matt was going to be receiving the medal — to me, that made more sense … With the actions of him, and some of the other guys, it made a horrible position just a little bit tenable.”

Williams said that it hasn’t “sunk in yet” — but, “maybe tomorrow,” when President Donald Trump presents him with the nation’s highest military award. As for what it will be like to head back to Fort Bragg wearing the nation’s highest military award around his neck, Williams isn’t totally sure what to expect.

“To be honest with you,” he told reporters. “I hope I can wear the medal with honor and distinction and represent something that’s much bigger than myself, which is what it means to be on a team of brothers, and what it means to be an elite Special Forces soldier. … As far as the day-to-day goes, I’m hoping to return back to my unit, get back to my team, continue training and get my current team ready for whatever comes next.”