Unlike the robust recruitment efforts of World War I and World War II, recruitment today is more focused on maintaining a standing military. As such there’s more emphasis on character, skill, and career development instead of a call to arms in response to a specific threat.

The most famous recruiting poster in U.S. history, it was created by James Montgomery Flagg, who used himself as the model for Uncle Sam. The poster was enormously popular and used extensively during World War I and World War II.Image via National Archives

Viral campaigns, Hollywood blockbusters, and massive television promos have all but replaced the recruitment poster. However, they remain an important part of the military’s history and offer insight into the social and cultural trends that the services once played off of to draw recruits.

While many military recruitment posters are iconic, such as James Montgomery Flagg’s “I Want You,” they weren’t always so on the nose.

Military recruitment posters were traditionally placed in very public spaces: post offices, town squares, city halls, and of course, in military recruitment centers. Prior to television, radio, and the internet, they were the cheapest way to get the government’s message to the public.

Related: The 1970s Marine Corps commercial that will actually make you want to re-enlist »

“All of them are designed to send a message that the reader would understand quickly and that would pair this catchy wording with an equally catchy image,” explained Bruce Bustard, a senior curator at the National Archives, in an email to Task & Purpose. “They are the equivalent of the brief ads that come up on websites. They want to grab your attention.”

The National Archives boasts one of the largest collections of U.S. military posters, between 3,000 and 3,500, with the vast majority aimed at recruitment during World War I and II, explained Billy Wade, a senior archivist with the National Archives’ Still Pictures Branch.

While the world wars marked the medium’s heyday, recruitment posters were in circulation long before then. The earliest posters focused on financial compensation and practical benefits for those enlisting, but around the early 1900s and well into World War II, they began to tug more on heartstrings than pockets. By World War II, military service was so closely tied to patriotic duty, sex appeal, and a life of adventure, that they didn’t bother to mention financial compensation.

Check out these eight military recruitment posters from National Archives ranging from the 1800s all the way to World War II.

This broadside dates from the 1799 Quasi-War, an undeclared war between the United States and France that took place almost entirely at sea. Typically this style of poster, called a broadside, didn’t contain imagery, but this shows U.S. troops in uniform in an array of positions. Even as far back as 1799, the military knew they could draw recruits with a slick uniform.

The message here is pretty direct. Don’t get drafted. Enlist!

Circulated in 1862, this broadside from the Civil War addressed the pending draft in the Northern States.

“It suggests that in addition to the various bounties a recruit would get for joining the Navy, he would also avoid being drafted into the Army, which was, presumably much more dangerous,” explained Bustard.

To sweeten the pot, the poster boasts “$50,000 in prizes,” but just below that it explains that an undefined “large portion” of that money will be awarded to ships crews, but is mum on what the take home will actually be for individual sailors.

Another broadside from the Civil War, this was issued just after the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863.

Bustard explained that the poster offers “protection of colored troops,” which was meant to reassure African-American servicemen that if they were captured, the U.S. government would come to their aid.

“This was important because the Confederacy had announced that captured black troops would be treated as slaves and sold back into slavery,” explained Bustard.

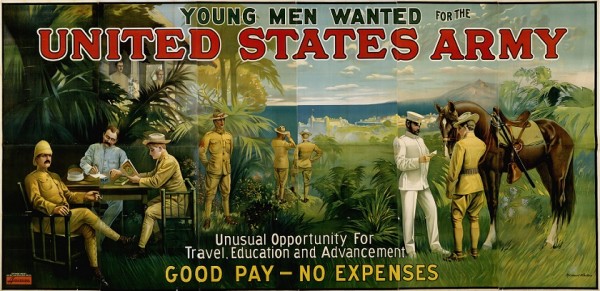

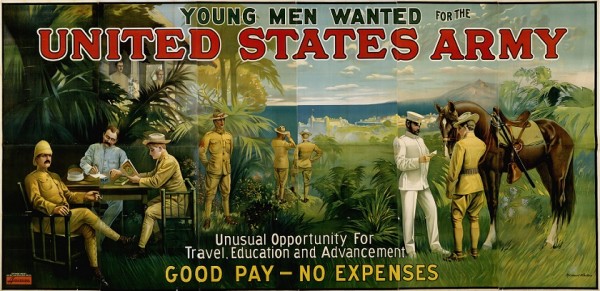

This poster from 1912 was designed to appeal to young men seeking adventure and travel. If you’re strapped for cash, longing for excitement and you see an advert guaranteeing adventure, good pay, and not-so-subtly implying a trip to a tropical paradise, chances are you might think about signing up.

It’s a tried and true recruitment method. Don’t believe it? Check out this Marine Corps Recruitment commercial from the 1970s that uses a similar technique.

Incorporating the motto of the newly created Tank Corps, this World War I-era recruitment poster was designed to imply a sense of excitement for what was at the time, an entirely new form of warfare, Bustard explained.

Featuring a “Christy Girl” model, the brainchild of artist Howard Chandler Christy, this World War I poster ran from 1917-1918 and was aimed at getting young men to enlist in the Marines.

“For their time, dressing a woman in men’s clothing was quite provocative and suggestive,” explained Bustard, who added that though the posters were quite popular, probably with young men, they were criticized as being “frivolous.”

Emblazoned with red, white, and blue, this is about as patriotic as you can get, not counting Uncle Sam. At the time, pilots were seen as sex symbols, akin to movie stars and sports heroes, explained Bustard, so it’s possible that this poster was trying to tap into that.

You know, something like “join the Air Corps, get a bomber jacket and all the babes.

This is pure machismo. The only way this poster could be more direct is if it led with the words: “Be a man and join the Navy.”

At first glance, it’s not entirely clear who this is targeting, whether it’s aimed at getting men to join the Navy, or to prompt their wives and girlfriends to pressure them to serve. The poster was produced in 1942 during the U.S. military’s first full year in World War II and a time when things were not going well for the Allies.

“This poster reinforces the connection between masculine strength and power and the armed forces,” explained Bustard. “I get an impression of the overwhelming armed might of the U.S. Navy. Perhaps this was a necessary connection at a time when things were not going well for the U.S.”