Dissatisfied with the quality of care and worried about reprisals from their command, service members are extensively seeking mental health care outside of the military, according to a new article in Military Medicine, an Oxford University Press journal.

The article’s authors concluded that military mental health professionals “must balance obligations both to patients and to the military command,” and the authors argue, “that ethical problems of trust and confidentiality become barriers to care,” according to an Oxford U.P. statement, provided to T&P; ahead of the article’s release. “Other barriers include stigma, a negative impact of seeking care on one’s career, beliefs that care would not be effective, and lack of appropriate services.”

The study, published in the Feb. 27 article, “Military Personnel Who Seek Health and Mental Health Services Outside the Military,” was based on responses from 233 service members stationed across the United States and overseas in Afghanistan, South Korea, and Germany between 2013 and 2016.

The vast majority of respondents — 93% — cited poor quality of DoD mental health care as their reason for visiting a civilian mental health provider. Fear of reprisal accounted for nearly half of all respondents’ eschewing military mental health experts, and mistrust of command accounted for 38%.

“Current wars have led to a devastating public health epidemic of suicide and mental health problems among veterans and active duty GIs,” Dr. Howard Waitzkin, distinguished professor emeritus at the University of New Mexico and the lead author of the study, said in a statement. “The military should encourage and support GIs’ use of civilian-sector services that do not involve the ethical conflicts inherent in military medicine and mental health care.”

The article describes these “ethical conflicts” as the tension that exists when you have a mental health care provider who’s either part of the chain of command or beholden to it. It’s hard to have an honest and candid conversation about your mental well-being, many service members believe, with someone who can simply order you to undergo a course of treatment, or suffer consequences for refusing to do so.

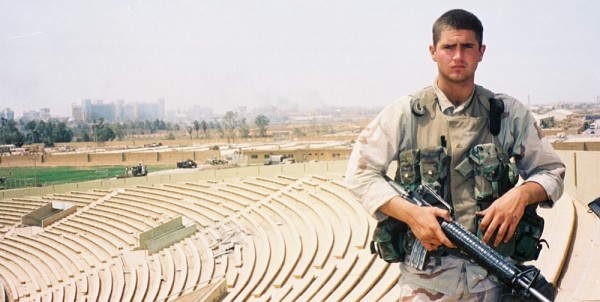

“There shouldn’t be this coercive hierarchy,” Matthew Ellis, a former Marine infantryman who suffered a traumatic brain injury following a pair of improvised explosive device strikes in Marjah, Afghanistan, told Task & Purpose. “I shouldn’t have to jump through hoops to try and get help.”

Ellis was injured in an IED strike while on foot on Feb. 18, 2010, and again less than a month later on March 10, while in an MRAP as part of the quick reaction force for 1st Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment.

After the second IED strike, which went off directly under his MRAP, he was evacuated stateside, where he received treatment at the Navy Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, in spring 2010. While there, he spent time in a mental health ward as part of his treatment for his TBI, but said he felt ostracized by his military care providers, and the feeling persisted once he returned to Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

“It’s the way that they force it, because it’s the military,” Ellis said, adding that it usually played out like so: “No, you’re gonna listen to what I say, because I outrank you.”

“But when it comes to my health, my mental health, I don’t care that I’m in the military,” Ellis, who left the Marines in 2011 as a sergeant, told T&P.; “I was on Ambien and it made me see shit, shadows and shit — and I was telling them that I was seeing stuff I wasn’t supposed to, and their response was, ‘You’re just going to have to deal with it.’”

Eventually, Ellis said, he refused to speak with his military mental health care providers, and he demanded an off-site consult. “I just wasn’t getting the treatment I needed from the military. It was really just a check in the box,” Ellis said, adding that during one of his initial appointments with a military psychologist, he had to explain to the doctor what a traumatic brain injury was.

“Why am I explaining this shit to you?” Ellis recalls asking. “You’re the fucking doctor.”

By August of 2010, he began seeing a civilian psychologist in New Bern, North Carolina, where “they knew exactly what was going on. It wasn’t someone straight out of an officers training school, who went to some damn medical course, now they’re just there. On the civilian side, the doctors were more trained, more competent.”

Related: For Most Vets, PTSD Isn’t The Problem, ‘Transition Stress’ Is. Here’s What That Means »

Ellis isn’t alone in his frustration over the quality of mental health care provided by the military. According to the Military Medicine authors, 93% of service members they interviewed reported that military mental health care providers were unresponsive to their needs.

“I felt like they were kind of going through the motions, like it’s one of those things where maybe you see it everyday, so you kind of stop caring,” Army Staff Sgt. Kimberly Hackbarth told T&P.;

Hackbarth saw military care providers while stationed at Fort Hood, Texas, and Fort Campbell, Kentucky, for post-traumatic stress disorder stemming from her nine-month deployment to Afghanistan in 2012, and eventually sought treatment off-base.

“I felt like they didn’t care as much about soldiers, and I don’t know if that’s because they’d seen soldiers who were faking having PTSD,” Hackbarth said. “But I just genuinely felt that they didn’t care as much as the civilian providers did off-post.”

In order to remedy the problems raised in the report — subpar care exacerbated by an uneven power dynamic between a care-provider and a patient — the authors suggest making non-military care more readily accessible. And there appears to be a significant need.

The troops polled for the study met the criteria for a mix of disorders, ranging from major depression, which affected 72% of respondents, to post-traumatic stress disorder (62%). Many respondents also met the criteria for generalized anxiety disorder (20%); panic disorder (25%); and alcohol use disorder (27%). Roughly one-quarter of the troops surveyed had a history of pre-military mental health treatment.

“Due to inherent contradictions in the roles of military professionals, especially the double agency that makes professionals responsible to both clients and the military command,” the article concludes, “the policy alternative of providing services for military personnel in the civilian sector warrants serious consideration.”

WATCH NEXT

Want to read more from Task & Purpose? Sign up for our daily newsletter »