You might be surprised to know that one of the most influential patriots of the American Revolution was once referred to as “a corrupt and unprincipled rascal” by U.S. President James Monroe. Monroe was speaking of James Swan, a name that is virtually unknown today, but one that should be in the panoply of founding fathers for the simple reason that he paid off the extensive American financial debt to France singlehandedly.

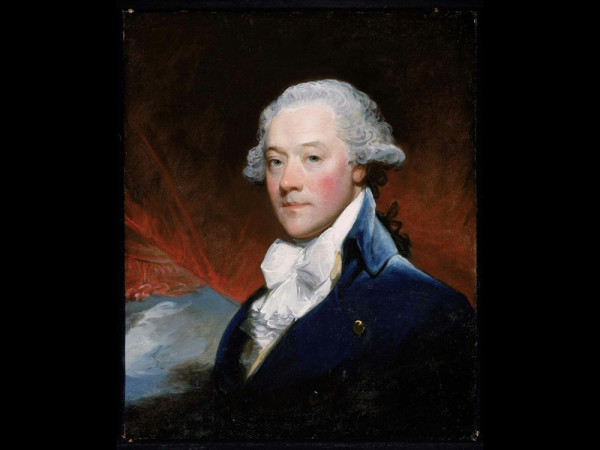

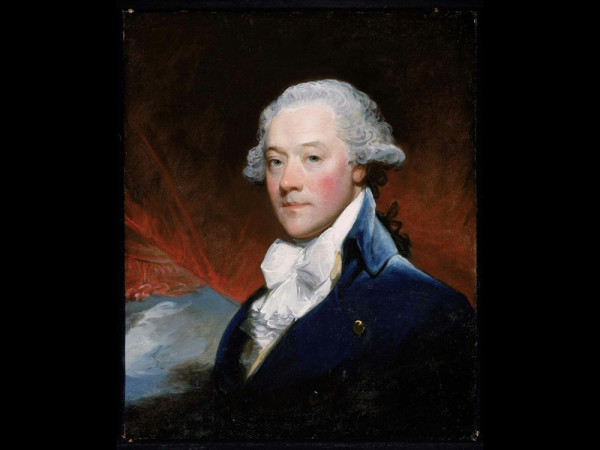

Swan was born in Fife, Scotland, in 1754 and emigrated to Boston in 1765. Here he applied himself to his education, essentially teaching himself everything that he could about finance. As a young clerk, he rubbed elbows with many influential Bostonians, including Henry Knox, who would become the first secretary of war. When Swan was barely 19, he penned a work on Britain and the African slave trade. It was published in 1772 and was a scathing rebuke of the practice, written from an economic perspective. Because of his youth,and his anti-British propensities, Swan got caught up in the growing anger in Boston over the unfair British taxation in the colonies. Therefore it was only natural that he take part in the infamous Boston Tea Party of 1773, where presumably the young Scotsman was highly amused to be destroying the king’s tea while dressed as an American Indian.

Swan celebrated his twenty-first year of life as a colonial militiaman, fighting at the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775, where he was wounded twice. He rose through the ranks of the colonial militia, eventually being promoted to the rank of major and occupied the position of adjutant general for the state of Massachusetts. Not only this, but he was still an active financier and used his growing wealth to pay for the many military expenses that Massachusetts could not meet. In addition, he shared his economic policies for Massachusetts with neighboring colonies, essentially acting as the Adam Smith of the American Revolution. During the war he also financed several privateers. By the time the war ended in 1783, Swan was a well-respected soldier and was friends with men such as George Washington, Henry Knox, and the Marquis de Lafayette. Married in 1776 to an heiress, he was also incredibly prosperous.

Swan reportedly owned over 2.5 million acres in what is now West Virginia, Virginia, and Kentucky prior to the war. During the war, he sold off this property to finance the Continental Army. When the conflict ended in 1783, a grateful Virginia gave him rights to even more land in the west. He was listed as one of the most wealthy men in Boston at only 29 years of age. An affluent Swan and his family were living the high life in the new United States.

As ever in finance, what goes up must come down. Swan soon encountered financial troubles, and left for France in 1787 to see if he could revive his fortunes working with his old friend Lafayette. He soon obtained government contracts from France for lumber, flour, grain, and other items, which helped him restore his wealth. The French Revolution began two years later, making France a hostile place for those who had been friends of the royalty. Swan somehow managed to navigate the political waters of the revolution and continue to make money.

The United States in 1795 was still struggling to pay off its own debts from the American Revolution. The Continental Congress had borrowed heavily from other countries, namely the Netherlands and France, to pay for its bid for independence. Now the French were calling for all American debts to be paid as they themselves struggled to finance their revolutionary armies. The debt exceeded $2 million and the United States saw no way to immediately pay it off. In stepped Swan, who privately assumed the entire debt. Like the good capitalist that he was, he then sold off the debt to private U.S. investors for a profit. This enabled the U.S. government to avoid the diplomatic embarrassment of being unable to pay off its foreign creditors and to get on a more secure financial footing.

Swan could have retired in the United States at this point, but he went back to France in 1798 to ensure that his business investments there were secure. When the French wanted to make a deal for the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, Swan was able to assist the U.S. in providing capital.

In 1808, a business partner accused him of owing a debt of two million francs. Swan flat out denied any such thing. But at this point his luck had run out and the ever-changing French government threw him into debtor’s prison. He could have paid this debt, but on principle and as a man of honor, he refused. This did not stop him from paying the debts of the other men who were imprisoned with him and he soon became a well-beloved and respected person in the prison. With money sent by his wife, Swan rented out apartments in his name across from the prison, where he held parties and other events for his friends, always with a seat left empty for himself. His family lived comfortably in Boston and Swan contributed to many charities in that city. In 1819, he wrote an address to the U.S. government on the advisability of using paper money rather than gold and silver for national currency, 50 years before this was eventually adopted by the U.S. Treasury. He was far from idle. However, it was not until 1830 that Swan was released from prison. By that time, his wife had died, his children were grown, his fortune had been spent, and most of his friends had either moved on or died.

Now an elderly 67 years of age, without wife, family, or friends, Swan was alone. His one wish was to see his old friend Lafayette, which apparently he did. The following day he died.

Swan is presumably buried in Paris, but the location of the grave of this generous patriot is unknown. His legacy in the history books seemed to disappear with him as well. Monroe had called him a rascal, which may have contained a kernel of truth given the sometimes underhanded nature of business dealings in the 18th century. However, rarely is an individual one dimensional and Swan certainly demonstrated more fine qualities than ill. Without his financial support, the great American experiment may have died in the fire of the war for Independence or fallen apart due to financial insolvency.