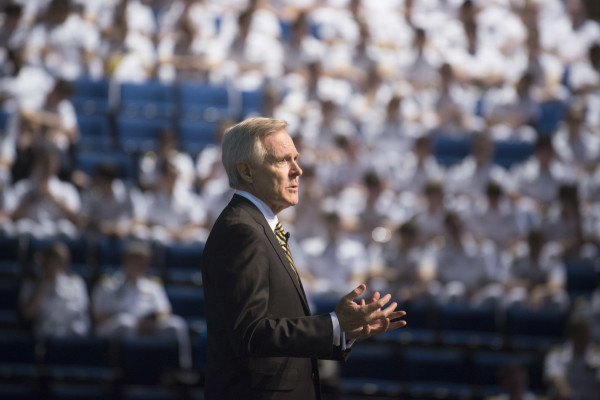

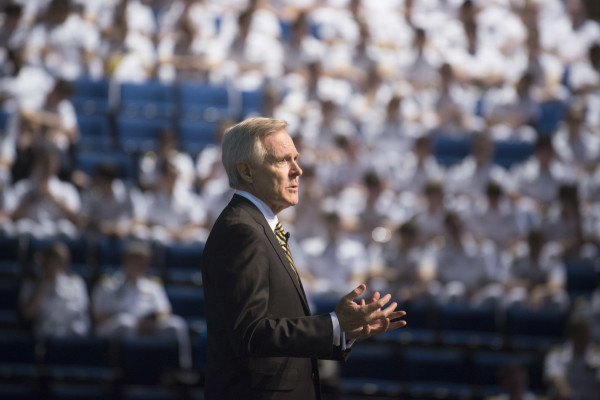

On Wednesday, Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus unveiled a slew of transformative personnel reforms during a speech at the U.S. Naval Academy. At the opening of his remarks, Mabus told the assembled midshipmen that their careers would “be defined by flexibility, transparency, and choice.” To a socially networked generation, this strikes the exact right tone. Over the past 50 years, our technology has evolved to meet emerging threats. Yet, our promotion models have not kept pace with an evolving society. Recognition at the highest levels of this paradigm shift is commendable.

While much of the media focused on Mabus’ proposed increase in maternity leave, physical fitness changes, and elimination of Navy Knowledge Online-based general military training, the most revolutionary reforms proposed revolve around promotion, career, and education opportunities. These will be hard to accomplish, but are necessary to ensure our Navy appropriately rewards the right folks.

Eliminating year groups and minimizing the “golden path”

The promotion process for military officers is about as inside baseball as processes come, but ensuring that the right people are promptly promoted in accordance with their performance is vital to retaining the best leaders and providing combat success for our military.

As it stands now, officers are only eligible for promotion based on the year they commission. Year-group-based promotion opportunity is a requirement of the 1980 Defense Officer Personnel Management Act, in order to ensure the right number of each grade of officer is maintained. However, it rewards timing over merit and treats all officers as interchangeable widgets.

This has profound implications for how officers are rated. Typical tours are two-to-three years in length, and most officers can expect to get their annual “high-water” fitness report during the last portion of their tour. Commanding officers are incentivized to rank more senior, but potentially lower performing officers, ahead of younger, more capable ones. Since younger officers have longer to “prove themselves” and get the requisite rankings for promotion within future reports, a low ranking earlier in their tour does not matter all that much as long as the trend is improving.

With the elimination of year groups, this will no longer be required. Indeed, more senior officers within the same pay grade will likely still deserve higher rankings than their more junior counterparts — experience does matter — but superstars will be able to break out when they emerge. They will also not have to wait three years for their skill to be recognized by a promotion board. An “Early Promote” ranking may actually mean something going forward, instead of being a hard and fast requirement to simply promote on time.

This reform is a must if we want to break out of an Industrial Age personnel management model. However, it will take cooperation with the other services, and even more importantly, the consent of Congress. This will be no easy task, but the time is right. Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter and Senate Armed Service Committee Chairman John McCain have both publicly spoken to the need to reform talent management.

Perhaps a bigger challenge to integration will be within sequestered promotion boards. It will likely take years for the cultural acceptance of merit over timing to take hold. While flag officers frequently promote after only a year or two in a specific grade, it is almost unheard of for officers between the ranks of ensign (O-1) and captain (O-6) to be promoted before they are “in zone.” “Below zone” selects — those selected for promotion before their year-group peers — are so infrequent in the Navy that when someone is promoted early, it can actually have negative consequences for future timing and promotion opportunities.

Furthermore, those officers who make promotion selections will be predominantly made up of officers who grew up and thrived on the year-group system. Well-written board precepts will be required to properly integrate this new model. Indeed, it may only be successful if commissioning classes of 2017 and beyond are included, while currently serving officers operate under a phased-out, year-group model.

Officers will still need to hit certain milestones for promotion. You probably should not be a destroyer commanding officer without first having been a surface warfare junior officer. However, more diverse experiences, or shorter tours, may be possible for high-performing individuals. More experience may also be available for those qualified, but who require a bit more time to reach the requisite level of performance.

Words are important, but actions matter more. If the secretary is successful in pushing this through an entrenched bureaucracy, he will have accomplished something of enduring significance.

Educational and industry opportunities

One of the greatest assets to my naval career was the network of civilians I was exposed to as a Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps student during college. I was introduced to ideas and professions I never would have considered in a cloistered military-only environment, and the lessons paid off in spades during my tenure as an officer.

Civilian-graduate education opportunities and fellowships have always been possible in the Navy, but up to this point, were frowned on (especially in the naval aviation community), rarely appropriately leveraged, and very rare. With the secretary’s announcement, this reality may be shifting.

Eliminating the aforementioned year group promotions will be the first step in full graduate-education integration. If the reforms are fully integrated, no longer will officers be tied to a career “clock” that narrows their options. If an officer chooses to pursue graduate education now, they will be able to still fit it within a normal career, meeting other operational milestones that are critical for developing tactical and strategic leaders.

Furthermore, sending our best performing senior officers to interact directly with industry through the “Security of the Navy’s Industry Tour” program will enhance warfighting effectiveness. Right now, fellowships with industry and academia are rarely found in flag officer biographies — they are often reserved for successful post-command officers who nonetheless are unlikely to make flag. But by reserving slots, and institutionally encouraging these tours, our future flag-level leadership will be well-served by understanding how other organizations manage challenging problems. The contacts and methods they gain will pay massive dividends while navigating the inevitable fiscal and strategic challenges that come with being an admiral.

This experience will also helping to narrow a growing civilian-military divide. Industry has just as much to learn from successful military operations and leadership as the military does from industry. And since our ultimate boss is Congress — he who holds the purse strings — informing influential political constituencies of the value of our Navy from our very best will greatly benefit national security at large.

The way forward

As with all revolutionary initiatives, the announcement is just the first step on a long journey. Execution will be challenging, and there will undoubtedly be institutional resistance. However, there is significant momentum to make the secretary’s vision a reality. The Navy has set the conditions for ensuring our most agile and useful asset, our people, are fully utilized to fight and win our nation’s wars.