It may have been a while since the last time two service members met at dawn to seek satisfaction over an insult to their honor, but the Uniform Code of Military Justice still makes clear the troops are not allowed to engage in duels.

Article 114 of the UCMJ lists dueling as one of the proscribed “endangerment offenses,” and it goes into detail about exactly how service members can get into trouble for fighting a duel or knowing that a duel is about to take place and not alerting the proper authorities.

Pentagon spokesman Lisa Lawrence said the language of Article 114 explains that dueling remains outlawed because it is “likely to produce death or grievous bodily harm to another person.”

Dueling was also outlawed under the 69 Articles of War, which Congress passed in 1775 to govern the Continental Army during the American Revolution, as well as the 101 Articles of War, which served as the basis for the military’s justice system from 1806 until 1951.

After the UCMJ went into effect, dueling was initially listed as its own offense as Article 114 until 2016, said retired Marine Lt. Col. Colby Vokey, who is now a civilian attorney who represents service members.

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest in military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

“Congress changed the article and called it ‘Endangerment Offenses’ and just included dueling as one type of endangerment offense,” Vokey said. “I have not read any of the congressional record regarding the 2016 change, but I believe it was made to deal with possession of weapons by service members, as it now includes discharge of a firearm and carrying concealed weapons.”

Vokey said he has never been involved in cases in which service members have been charged with dueling, nor is he aware of any such cases being adjudicated under the military’s justice system.

When Task & Purpose asked the military branches how many service members have been charged with dueling, military officials had few answers. An Army spokeswoman said the service did not find any instances of disciplinary actions for dueling under Article 114 of the UCMJ going back to 2012, when its case management system came online. Disciplinary statistics for dueling prior to 2012 were not readily available.

As for the other services: The Air Force found no results for dueling in its database; the Navy also found no instances within the past eight years of sailors being charged with dueling under Article 114; and the Marine Corps suggested that Task & Purpose file a Freedom of Information Act request on the matter and also provided the link to the Navy’s Judge Advocate Corps website.

It is unclear if any service members have taken up dueling after leaving active duty.

“The Department of Veterans Affairs has no data or information on treatment or claims related to dueling,” VA spokesman Randall Noller told Task & Purpose.

The reason why the UCMJ still has a law against dueling on the books is not clear when the U.S. military is struggling — and failing — to solve more pressing problems including suicides, rising numbers of sexual assaults, and widespread sexual harassment in the ranks. (It is also noteworthy that while dueling has been expressly forbidden since 1775, sexual harassment was not listed as a specific offense under the UCMJ until this year.)

Retired Marine Lt. Col. Guy Womack, a civilian defense attorney who represents service members, said he is not aware of any recent cases involving service members dueling, but he added, “There is no reason to delete the provision from the UCMJ Article, I suppose, just in case there ever is a duel.”

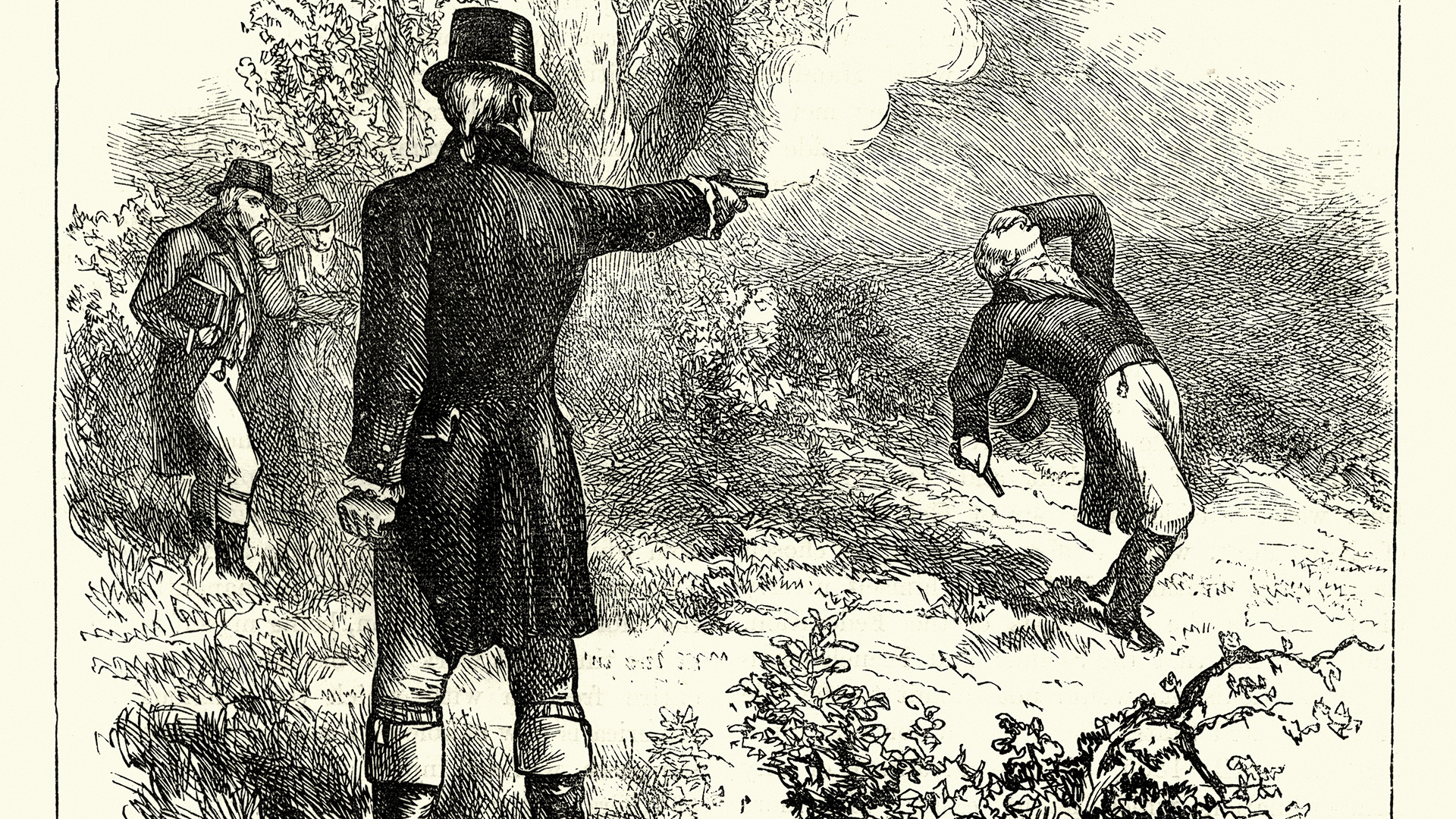

To understand why the military even has a law outlawing dueling, it is important to recognize how widespread dueling was in the United States before the Civil War. Alexander Hamilton, a former Army major general, was killed in an 1804 duel with then-Vice President Aaron Burr, who was never charged with Hamilton’s death.

It was also common at the time for Navy officers to settle disputes with pistols or swords, according to a 2004 “Smithsonian Magazine” article written by Ross Drake.

“Between 1798 and the Civil War, the Navy lost two-thirds as many officers to dueling as it did to more than 60 years of combat at sea,” the article says. “Many of those killed and maimed were teenage midshipmen and barely older junior officers, casualties of their own reckless judgment and, on at least one occasion, the by-the-book priggishness of some of their shipmates.”

Even Commodore Stephen Decatur — one of the Navy’s earliest heroes, who famously set fire to the captured frigate USS Philadelphia during the First Barbary War — was killed in an 1820 duel with another Navy officer, whose court-martial he served on. Ironically, Decatur had limited dueling when he was commanding officer of the heavy frigate USS United States.

“As captain, he required that all midshipmen consult with him before declaring or accepting a challenge for a duel,” Janine Peterson wrote for “Military History Magazine” in 2019. “His goal was not to abolish dueling, since it played a role in maintaining the bravery and honor of the Navy, but rather to eliminate frivolous contests by giving the men a chance to calm down.”

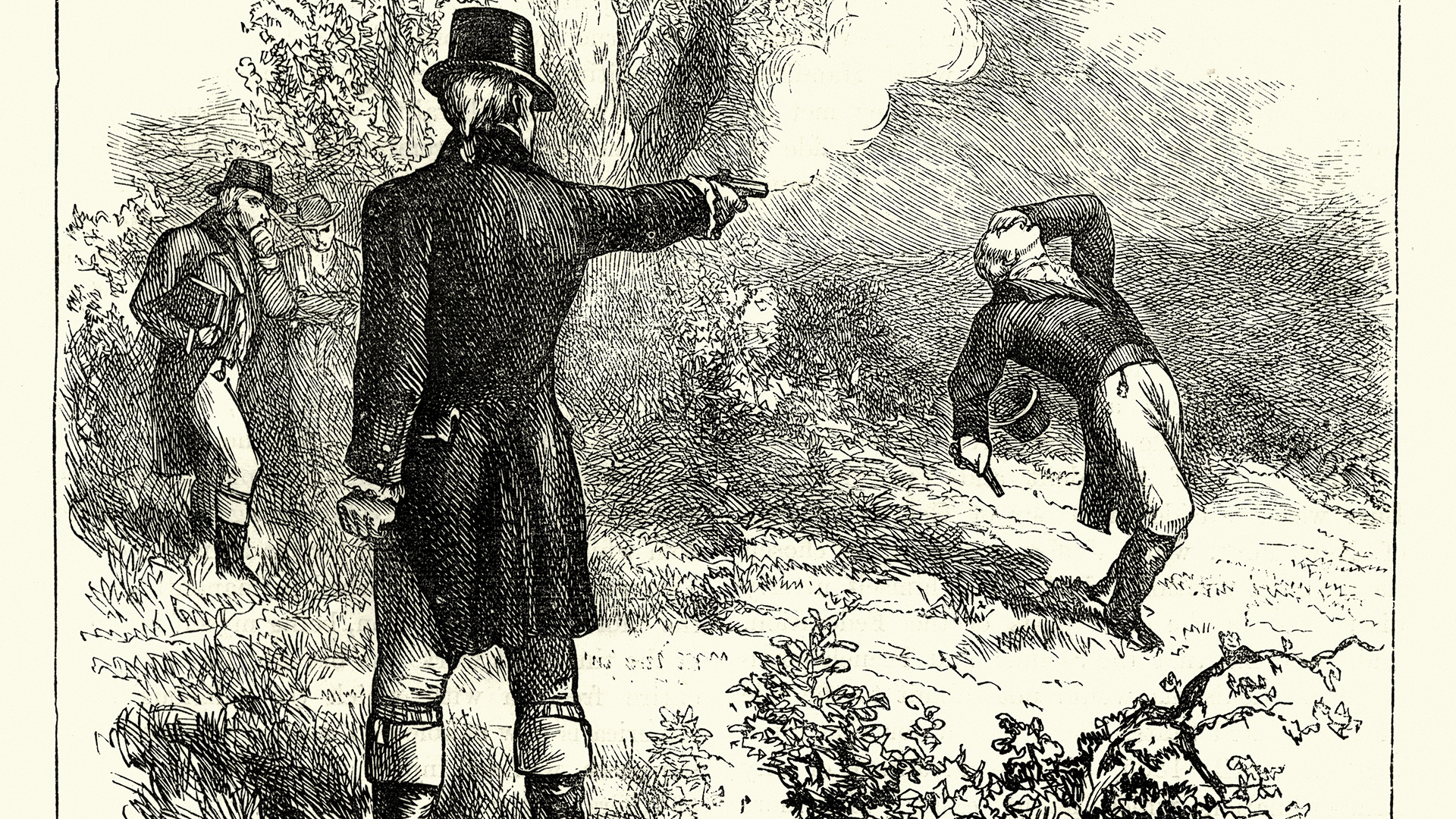

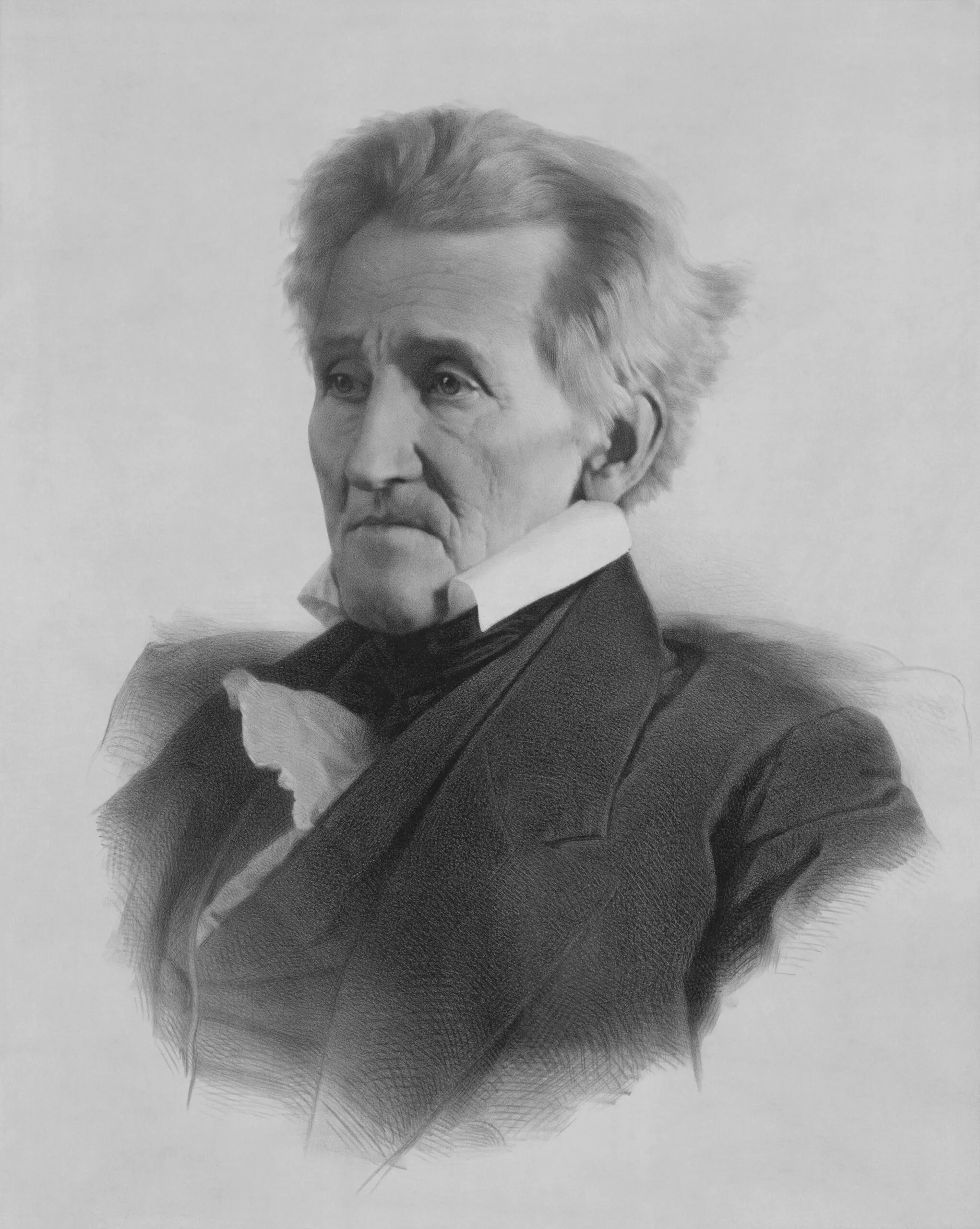

Andrew Jackson, who went on to become president, was an avid dueler. Jackson survived after being shot in the chest during an 1806 contest with a man who had insulted his wife, and seven years later he got into a Quentin Tarantino-style gunfight with Army Lt. Col. Thomas Benton, his military aide during the War of 1812.

The dispute was sparked by an earlier duel involving Benton’s brother that Jackson had helped to arrange. On Sept. 4, 1813, Jackson and two accomplices ambushed Benton and his brother in a Nashville tavern. Jackson first attempted to horsewhip Benton, but the confrontation quickly devolved into a battle involving pistols, daggers, and at least one sword cane. Jackson ended up being shot in the shoulder. Benton survived despite being stabbed several times.

“Fortunately the carnage was limited by the fact that the Colt six-shooter had not yet been invented; the fire-belching smoothbore pistols the antagonists used were not particularly accurate and, once fired, were useless,” Elbert B. Smith wrote for American Heritage magazine in 1958.

Another future president came close to fighting a duel when Abraham Lincoln was challenged in 1842 by James Shields, who was then Illinois’ state auditor. Lincoln decided to use broadswords instead of pistols because he was much taller than his opponent, Kelsey Johnston wrote in a 2014 article for the American Battlefield Trust. Lincoln demonstrated his long reach by cutting the branch off a tree high above Shields’ head, allowing both men to reach a truce before fighting.

Shields later became a brigadier general in the Union Army. In 1862, Shields was seriously wounded after fighting Confederate Maj. Gen. Stonewall Jackson. Lincoln nominated Shields for his second star afterward.

In light of all that, perhaps it is a good idea to keep the dueling provision in the UCMJ. In the age of Twitter, TikTok, and Instagram, insults among service members fly so thick and fast that if dueling became popular again, there would be no one left to defend the country.

This story was updated on June 22 to include information on how the Navy found no instances within the past eight years of sailors being charged with dueling under Article 114 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

The latest on Task & Purpose

- ‘Mad Max’-style technicals have become a staple of Ukraine’s fight against Russia

- The difference between Air Force and Navy pilots in one short video

- Watch the ‘Top Gun: Maverick’ film crew get buzzed by an F/A-18 during filming

- Three Navy commanders relieved of duty in the past week

- Hollywood has spent $16 million training Chris Pratt for war

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.