Today, most of us know that veterans with general discharges lose access to the Post-9/11 GI Bill — and full disclosure, I’m one of those guys.

But, who determines who is a veteran and what benefits they receive has changed. Today, when a “former service member” with an other-than-honorable discharge goes to a VA OIF-OEF clinic, he or she can be told “for the purposes of VA benefits and eligibility, the VA doesn’t consider you a veteran.” Friends of mine who spent a year in Sadr City, and another 16 months fighting in some of the bloodiest battles in Iraq as part of the troop surge have been told, “You’re not a veteran.”

At a recent roundtable discussion, Bradford Adams, a staff attorney for veterans service organization Swords to Plowshares, posed a question to the community: “Is it reasonable that commanders can ban a combat veteran from a lifetime of benefits for minor misconduct?” Adams explained that there’s a difference between “reward benefits” such as GI Bill education benefits and federal hiring preference, and “basic veteran services” like health care, housing for those at risk of homelessness, and disability compensation.

Related: VA is denying benefits to veterans with bad paper discharges at unprecedented rates »

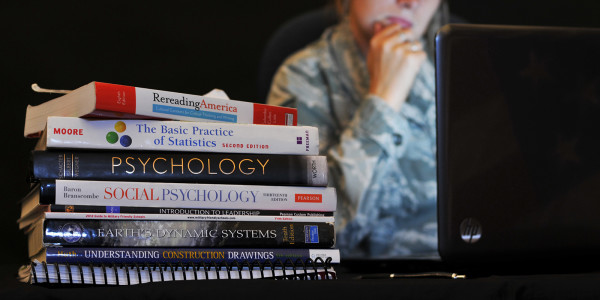

On March 3, 2016, Marine colonel turned congressman, Mike Coffman of Colorado, introduced two bills to the House of of Representatives: HR.4683, otherwise known as the Fairness for Veterans Act, and HR.4684 known as the Veteran Urgent Access to Mental Healthcare Act. The Fairness for Veterans Act shifts the burden of proof in favor of veterans diagnosed with service-related post-traumatic, traumatic brain injury, or military sexual trauma who are appealing less-than-honorable discharges to the Military Discharge Review boards. This bill has received a lot of attention lately since it’s recently been revealed that tens of thousands of troops with post-traumatic stress and traumatic brain injury have been administratively discharged despite attempts by Congress to protect them.

The Veteran Urgent Access to Mental Healthcare Act, however, hasn’t received quite the same fanfare. That bill would allow the VA to provide nearly all former service members with an initial mental health assessment and health care services related to suicide prevention. The only exception would be for those who received a bad conduct discharge or dishonorable discharge as a result of a general court-martial.

This bill isn’t a radical change. It’s a return to the spirit of the original GI Bill of Rights, where commanders did not have authority to issue a lifetime punishment for minor misconduct. For my generation who volunteered to serve after Sept. 11, I think this is a right worth fighting for.

As an advocate for veterans with less-than-honorable discharges, I’ve noticed that some members of the post-9/11 era have a certain mindset about benefits and discharge status that previous generations of war veterans don’t seem to have quite as much. On virtually every article advocating for an expansion of veterans benefits to those with less-than-honorable discharges, a handful of commenters seem to have the impression that something’s being taken away from them and their honorable discharge if a combat veteran with an less-than-honorable discharge gets to see a shrink. I believe this is a result of the “commander-decides-your-fate” mentality, which is all my generation has ever known.

“Who is a veteran” is complicated enough of a question that the Congressional Research Service was commissioned to come up with an answer, issuing a report last year that revealed the nuance of this topic.

According to Title 38, a veteran is defined as a “person who served in the active military, naval, or air service, and who was discharged or released therefrom under conditions other than dishonorable.” The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, more commonly known as the original GI Bill of Rights, applied veterans benefits to everyone in this intentionally broad category.

According research released by Swords to Plowshares, the intent of Congress with the 1944 act was “simplification and expansion” of the implementation of veterans benefits. Congress recognized that at the end of World War II, the country could be facing a large enough unemployment crisis to trigger a second depression. To avoid this, it issued benefits such as disability compensation, health care, education, vocational rehabilitation, and home loans to nearly every veteran who hadn’t received a dishonorable discharge as a result of a general court-martial.

Since 1944, however, the definition of veteran, and who is eligible for veterans benefits has significantly narrowed. With the switch to an all-volunteer military and a reduction in forces during peacetime after Vietnam, the original intent of the GI Bill of Rights was lost.

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter granted clemency to veterans who went AWOL during the Vietnam War. Congress rebuked this by passing Public Law 95-126, which denied entitlement of veterans’ benefits to those with other than honorable discharges. This, according to Kent Eiler, the project director of the New York City Bar Association’s Veterans Assistance Project, “was a deliberate effort by Congress at that time to twist the screws on vets with bad paper.” That’s where we get the seemingly arbitrary ban on VA services for veterans who have gone missing for 180 days.

Related: What happens to veterans who received ‘bad paper’ discharges »

Education and other benefits gradually became a Department of Defense enlistment/re-enlistment tool rather than a right guaranteed by the Veterans Administration through the 1970s and 1980s. Although the benefits are still disbursed by the Department of Veterans Affairs today, a veteran’s eligibility for some benefits are now up to the discretion of commanders.

In light of this, I’d remind my fellow veterans that we’re supposed to take the warrior ethos to heart and never leave a fallen comrade.

Here are the facts: Veterans with less-than-honorable discharges are more likely to suffer from substance abuse issues, become homeless, become incarcerated, and go for years without treatment for the physical and mental wounds of war. Important to note, they’re also three times more likely to die by suicide.

Is someone pissing hot on a random drug test after two combat deployments worth making them a statistic?

The Veteran Urgent Access to Mental Healthcare Act is a simple, two-page bill with the potential to return the GI Bill to what it once was: the GI Bill of Rights, which Congress passed with an intent to protect veterans from lifetime punishments issued administratively by commanders. In doing so, the VA would be granted the ability to care for some of our most vulnerable brothers and sisters. Considering that 125,000 post-9/11 veterans have been excluded from basic VA services due to less-than-honorable discharges, I’m left to wonder, why is this a bill no one is talking about?