Every soldier in the Army who aspires to join the infantry, earn a Ranger tab, or become a paratrooper must pass through the gates of Fort Moore, Georgia to begin training.

As of this week, all those gates are named for battlefield heroes.

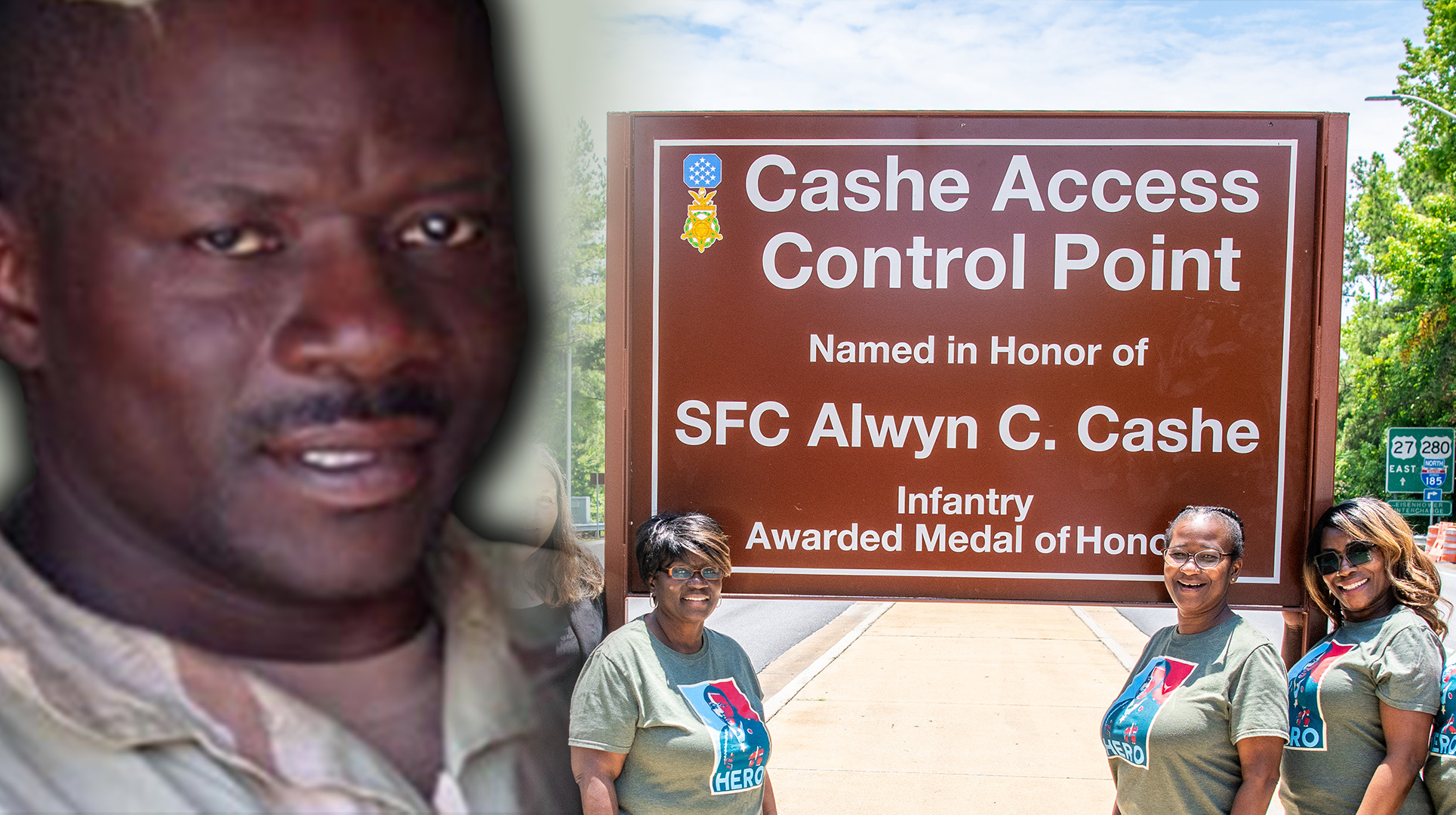

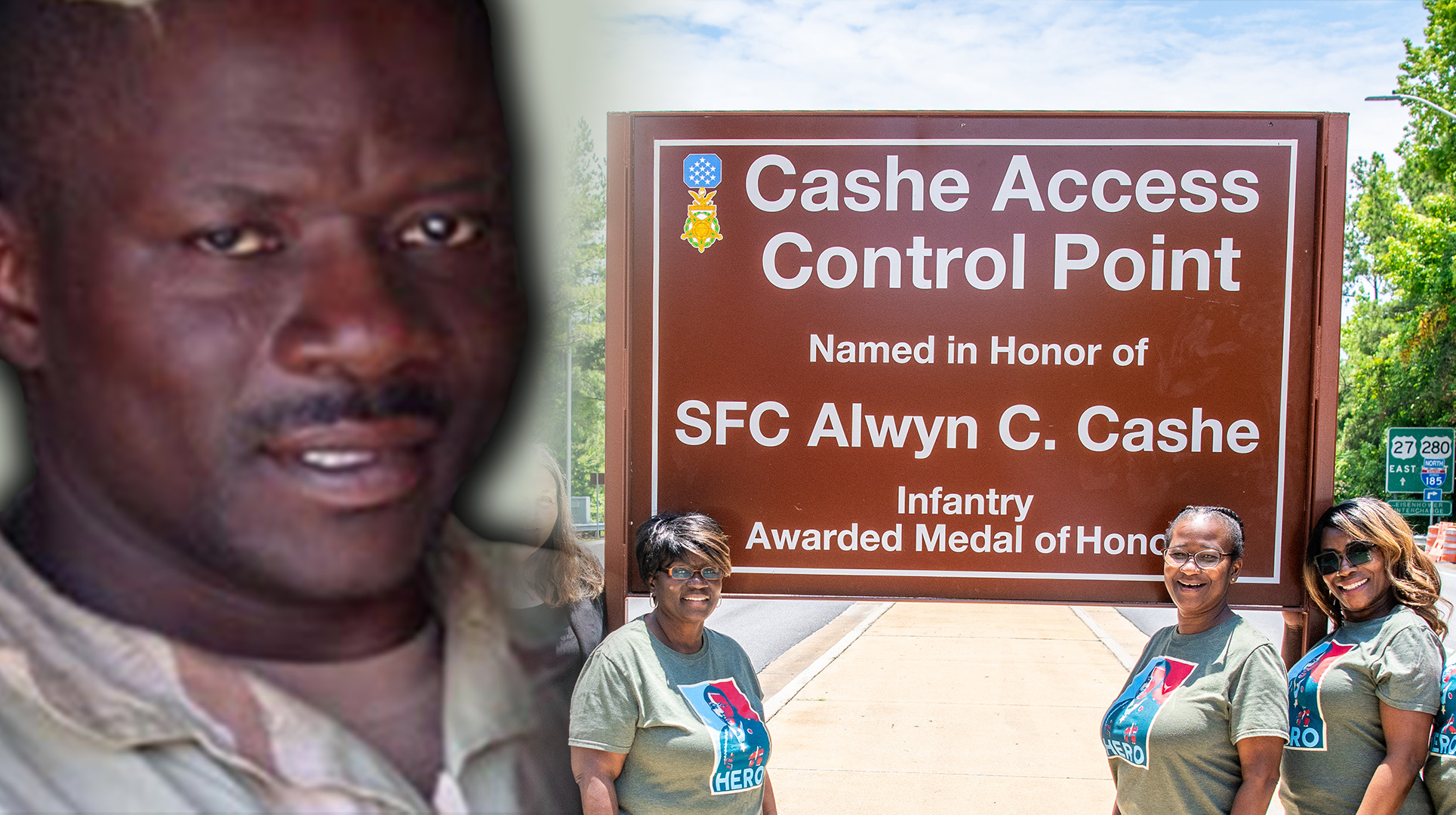

Officials at Fort Moore renamed a final entry point to the base Monday after Sgt. 1st Class Alwyn Cashe, a Medal of Honor recipient who repeatedly charged into a burning armor vehicle to save fellow soldiers in Iraq. Four other gates have been renamed since late last year.

At a ceremony last week, Cashe’s sister Kasinal Cashe White said the Army had chosen well in the gate named for her brother. The renamed gate is the primary entrance for the Sand Hill portion of Fort Moore, which is where the Army trains new infantrymen.

“Everybody that decides to be an infantryman, they’re going to have to come through that gate,” said Cashe White.

The Cashe Access Control Point is the fifth and final name change since November at Fort Moore. Other gates around the sprawling base are now named for Medal of Honor recipient Lt. Col. Ernest Childers, Lt. Gen. David Grange Jr., and Silver Star recipient Command Sgt. Maj. Basil L. Plumley — all icons in Army infantry lore — and Distinguished Service Cross recipient Chief Warrant Officer 2 Lafayette G. Pool, a legendary tanker who came to be known as “War Daddy.”

Cashe enlisted in 1989 as an infantry soldier, training at then-Fort Benning. He served in the 1991 Gulf War and then as a drill sergeant before being assigned to the 3rd Infantry Division. On Oct. 17, 2005, Cashe’s Bradley Fighting Vehicle was hit by an improvised explosive device, trapping soldiers inside. Cashe ran into the inferno, again and again, to free six or carry out six of them and an Iraqi interpreter. He died of his wounds weeks later.

Cashe posthumously received the Medal of Honor in 2021 as an upgrade to the Silver Star he was awarded for his acts.

Fort Moore was renamed in May 2023 from Fort Benning, dropping the name of a Confederate general as part of the Pentagon’s Naming Commission program. But unlike the controversial Moore/Benning change, the new gate names replace fairly innocuous labels.

Along with the Sand Hill gate now named for Cashe, the gate now named for Grange was formerly the Legacy Way gate, and the Pool Access Control Point, or ACP, was formerly the Harmony Church gate. The Plumley ACP is now the base’s main gate, long known as the Lindsey Creek entrance.

Other soldiers honored in the name change:

- Ernest Childers was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions in Oliveto, Italy as a 2nd Lt. in World War II. A Creek Indian, Childers was born in Broken Arrow, Oklahoma, and enlisted in the Oklahoma Guard in 1937. He was a first sergeant during landings in Sicily in July 1943, where he was given a battlefield commission. In Oliveto, Childers led a squad to capture an objective held by machine guns, snipers, and mortars, despite his own broken foot. according to his Medal of Honor citation, Childers led eight soldiers “up a hill toward enemy machine-gun nests. The group advanced to a rock wall overlooking a cornfield and 2d Lt. Childers ordered a base of fire laid across the field so that he could advance. When he was fired upon by two enemy snipers from a nearby house he killed both of them. He moved behind the machine-gun nests and killed all occupants of the nearer one. He continued toward the second one and threw rocks into it. When the two occupants of the nest raised up, he shot one. The other was killed by one of the eight enlisted men. 2d Lt. Childers continued his advance toward a house farther up the hill, and singlehandedly, captured an enemy mortar observer.”

- Lt. Gen. David E. Grange Jr. is viewed as one of the architects of the modern 75th Ranger Regiment. Grange saw action in World War II as an enlisted paratrooper in the Rome-Arno campaign, Southern France, Rhineland, Ardennes, and Central Europe. As an officer, he served in Korea and Vietnam and was one of just a handful of soldiers to earn three gold stars for combat jumps. In the Ranger community, Grange was a Ranger instructor as a captain in the 1950s and helped stave off the Army’s efforts to reduce the size of the Ranger program after World War II. By the early 1970s, Grange was named commander of the Ranger Department within Fort Benning’s larger School of Infantry as it prepared to stand up as the independent Ranger Training Battalion. The annual Best Ranger Competition is named for him.

- Sgt. Maj. Basil L. Plumley wore a Combat Infantry Badge with two stars on it, indicating direct combat in three wars. The son of a West Virginia coal miner, Plumley made four combat jumps in World War II, a fifth in Korea and was awarded a Silver Star for a nighttime battle in Vietnam in which a parachute-borne illumination flare landed on his company’s ammo dump. Plumley grabbed the flare and threw it clear of the explosives. Plumley was a Sgt. Maj. in the First Battalion, Seventh Cavalry during the Battle of Ia Drang Valley under then-Lt. Col. Hal Moore, whom Ft. Moore is named for. The battle’s story was the basis for Moore’s book “We Were Soldiers Once… and Young” which became a movie starring Mel Gibson. Plumley was remembered as hard combat leader who kept soldiers alive with iron discipline, intense training and his own courageous example.

- Lafayette G. Pool was one of World War II’s most legendary tankers, earning the nickname “War Daddy.” Pool earned both a Distinguished Service Cross and Silver Star, commanding three different Sherman tanks across France, Belgium, and Germany. In 81 days, his crew was credited with destroying 12 enemy tanks and 258 armored vehicles and self-propelled guns. He was knocked out of combat and the Army in a duel with a German tank in September 1944 that ended with Pool’s tank in a ditch and his right leg amputated above the knee. Pool re-enlisted in 1948 as an instructor and retired in 1969.

The latest on Task & Purpose

- Marines will land on Normandy beaches to commemorate D-Day’s 80th anniversary

- Air Force raises maximum amount for retention bonuses to $180,000

- Former Admiral’s $500,000 retirement job was a bribe, prosecutors say

- Army special operations officer under investigation after shooting

- Meet the soldier who is taking the Army combatives scene by storm