The facts of Pvt. Caleb Smither’s death are clear.

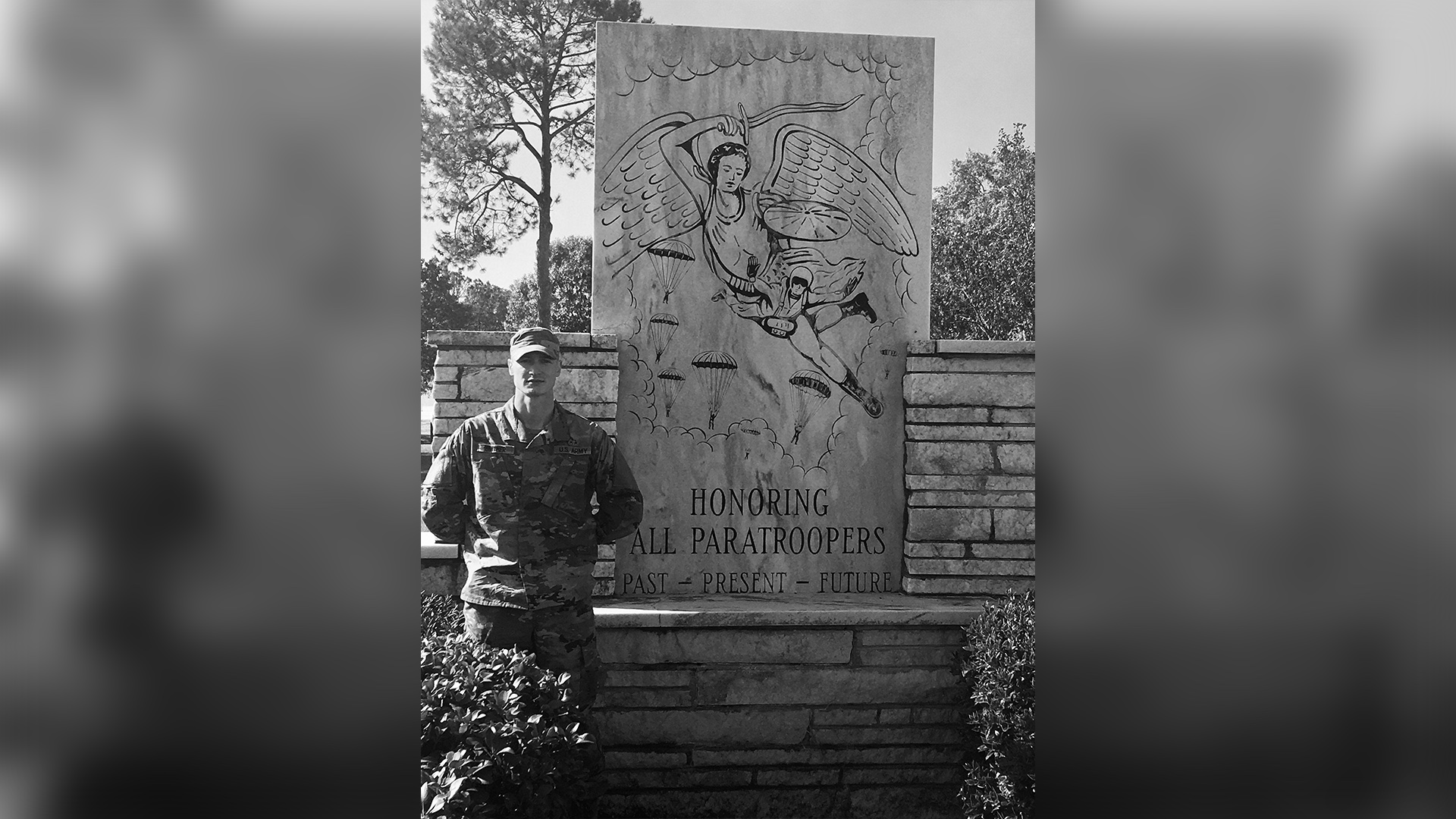

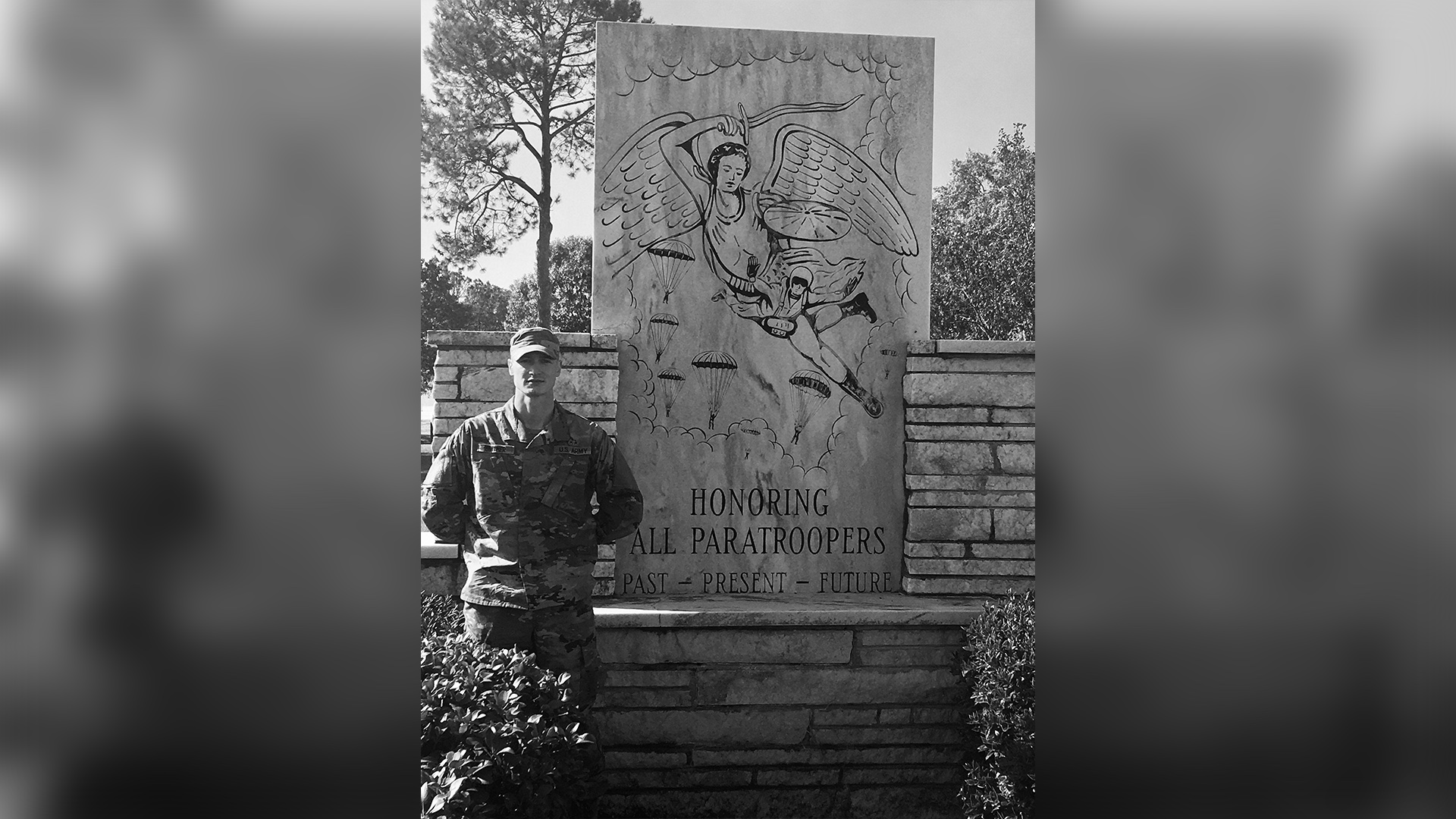

Smither was a private in the 82nd Airborne Division, assigned to the maintenance platoon of the 37th Brigade Engineer Battalion, part of the division’s 2nd Brigade, at Fort Bragg, now Fort Liberty. At some point in mid-January 2020, he hit his head in the motor pool. On January 14 he went to sick call and eventually found himself at the base’s Womack Army Medical Center. He went back again the next day and was given some degree of treatment, and told to recuperate in his barracks room. A four-day weekend was coming up, and no one in Smither’s chain of command seemed able to agree on how to check up on him.

That next Tuesday, January 21, he was found dead in his room.

The facts of Smither’s death are also very clear behind the legal question of who was responsible for his death: the Army has no responsibility because the healthcare provider who attended to Smither in the base hospital on January 15 was an independent contractor.

The doctor who was “the emergency room physician who saw PV2 Smither on January 15th is a non-personal services contractor and, as such, is not a DOD health care provider for the purposes of a payable claim,” according to the Army’s determination letter provided to Task & Purpose.

In other words, if you are an Army soldier, at an Army base, and you go to an Army hospital like Womack Army Medical Center, and receive treatment for an injury you received on duty or an illness that affects your job, and that if that treatment goes wrong, the Army may actually not be responsible in any way if that doctor or nurse is an independent contractor.

Have a problem with that? Take it up with that contractor’s direct employer, not the Army.

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest military news and culture in your inbox daily.

Or don’t if the Army waits too long to decide your case and exceeds the statute of limitations for medical malpractice lawsuits. In North Carolina, it is three years, and March 2023 – when the determination was issued from the Army – is of course more than three years since January 2020, when Smither died.

“The Army’s position is that Caleb was seen for two days and that the standard of care was met on the [January] 14th, but on the [January] 15th it was a contractor, so the law doesn’t provide for coverage for this type of claim,” said Daniel Maharaj, a lawyer for Smither’s family.

At the renaming ceremony last month that turned Fort Benning, Georgia into Fort Moore, the commandant of the Army Maneuver Center of Excellence, Maj. Gen. Curtis Buzzard, said that, “This is where our national treasure, our sons and daughters, come to train. And we make a handshake with America every time they arrive, and we maintain the trust and confidence of the American people.”

But when it comes to U.S. service members who die or are injured while on duty, though, legal technicalities still carry a lot more weight than a handshake deal.

In 1950, the Supreme Court ratified Feres v. United States, which prevented the families of service members from suing over injuries or deaths that resulted from service. In 2019, Congress passed the Stayskal Act. Named for a former Marine and Green Beret whose cancer diagnosis was delayed for several years when military doctors failed to read his chart, the law opened a window for medical malpractice claims against the military.

Still, in the intervening years, it has been difficult for anyone to actually win one of those claims.

In a review by the Army earlier this year of 202 medical malpractice claims against the Army, 144 were denied. Eleven parties had received settlement offers. Stayskal, the namesake of the law allowing service members and their families to pursue some form of compensation for medical malpractice, had his own claim denied in March, although the Army offered to pay him $600,000.

There was “no evidence that [Master Sgt.] Stayskal’s prognosis or chance of survival was adversely affected by the delay in the diagnosis of lung cancer,” said the finding from Stayskal’s case.

Essentially, while it is now possible to seek compensation for military medical malpractice, doing so is an uphill battle, which will be disputed at every chance.

“We’d been in contact with the JAG office and the command team, but at no point was it ever mentioned that there was a contractor involved,” said Maharaj. “It almost looks like another way the DoD is avoiding responsibility.”

The determination in Smither’s case is initial – Maharaj and Smither’s mother, Heather Baker, said that they are preparing a rebuttal.

In an October 2021 letter addressed to Baker’s congressional representative, the then-commander of the 2nd Brigade, 82nd Airborne Division wrote that the brigade was implementing changes and taking special consideration for head injuries.

“Once a month the battalion hosts a meeting with all the company commanders, the Physician Assistant (PA), and several agencies from post to discuss different aspects of the mental and physical health concerns of select paratroopers,” says the memo.

“If they’re going to say that the way Caleb died is okay, then you should wake up,” said Baker. “If it happens to him, it can happen to your son or daughter.”

The latest on Task & Purpose

- Air Force said AI drone killed its human operator in a simulation

- The Army says it’s made ‘significant improvements’ to its troubled new infantry squad vehicle

- What we know about China’s hacking of Navy systems

- Taliban moving captured US military vehicles and Soviet tanks to Iranian border

- Five juveniles arrested for attack on Marines caught on video