Editor’s note: This article was originally published on Sept. 9, 2021.

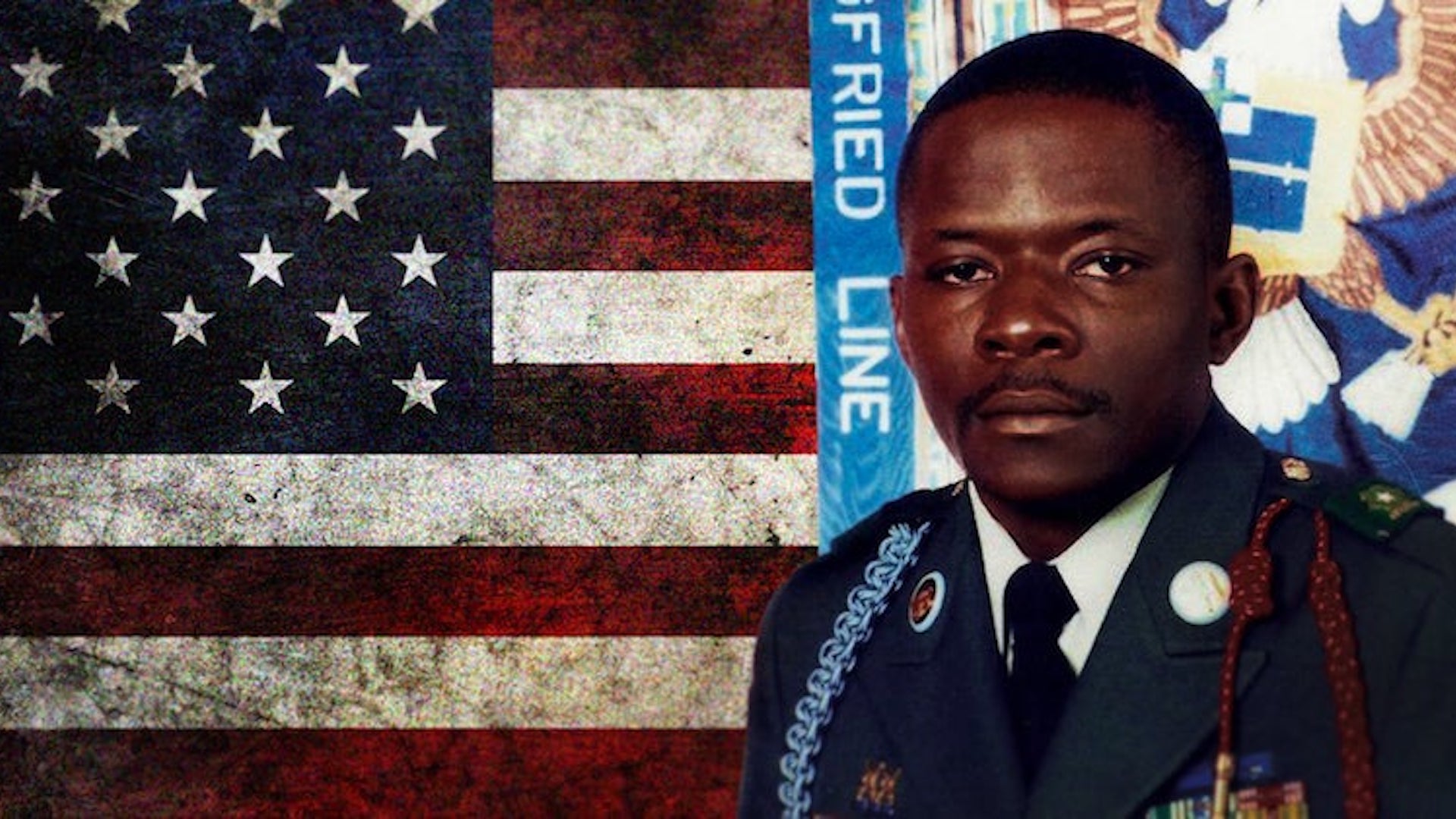

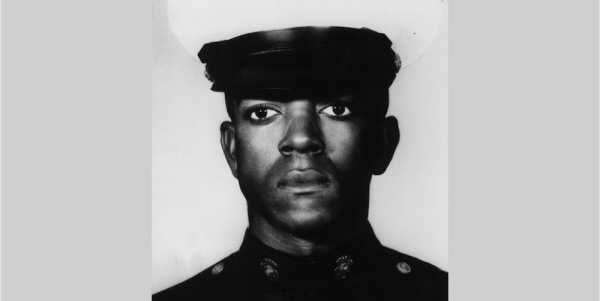

On Oct. 17, 2005, during an ambush in Daliaya, Iraq, Army Sgt. 1st Class Alwyn Cashe made a decision that ensured the survival of his men, at the cost of his own life. Drenched in gasoline, he walked into the still-burning wreckage of a Bradley Fighting Vehicle, and began pulling them out one by one. Three times he walked through fire to rescue his soldiers.

Nearly 16 years later, Cashe still has not been awarded the Medal of Honor despite receiving an endorsement for the award from the Pentagon that was forwarded to the White House nine months ago. After a lengthy campaign led by family members and soldiers who served with Cashe, in early January his Medal of Honor was approved by then acting Defense Secretary Christopher Miller.

Even so, the delays have continued.

A spokesman for the National Security Council said on Sept. 8 that there were no updates to share regarding Cashe’s posthumous Medal of Honor.

Although Cashe’s award package was sent to the White House from the Pentagon at the beginning of this year and the White House planned to move forward with it before the Jan. 20 inauguration, it was delayed after the attack on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6.

Kasinal Cashe White, Alwyn Cashe’s sister, said in March that she understood President Joe Biden was focusing on the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) as he got settled in office. As a registered nurse, she “thought it was more important to get these vaccinations out.”

She told Task & Purpose in early September that she’s been waiting to hear a date for the announcement from the White House, and has attributed the delay to the crisis that unfolded in August and September in Afghanistan. She doesn’t want to take attention away from the loss of 13 service members in Afghanistan, she said, but she’s ready for the journey to get her brother the recognition he deserves to come to a successful end.

And who can blame her? It’s been almost 16 years since Cashe lost his life after walking through fire to save his soldiers.

The 35-year-old combat veteran was on his second deployment to Iraq in October 2005, and was conducting route clearance with his platoon on the evening of the 17th. Cashe was a gunner in the lead Bradley Fighting Vehicle, which “struck a victim detonated pressure-switched [improvised explosive device]” his Silver Star citation says.

The explosion ignited the fuel cell in the vehicle, causing it to erupt into flames with the soldiers still inside of it. Cashe was only slightly injured in the explosion, but became drenched in fuel. But without a second thought, he immediately began working to get his soldiers out: There were six in the back along with the unit’s translator, as well as the driver, who had been burned.

“Flames had engulfed the entire vehicle from the bottom and were coming out of every portal,” the citation says.

Cashe went to the rear of the vehicle and began pulling soldiers out through the flames. As he worked, fire spread on his fuel-soaked uniform and then all over his body, but he kept going anyway. One by one he pulled the soldiers out, brought them to safety, and then returned for the others. Each time he went back, the fire spread further, burning Cashe.

By the time the company first sergeant arrived at the scene, Cashe was the most wounded soldier on the ground, suffering from second and third degree burns over 72% of his body. Still, he “refused to be loaded onto a medical evacuation helicopter until all the other wounded men had been flown,” the Los Angeles Times reported in 2014.

To the Air Force doctor who treated Cashe and his soldiers in Iraq, Maj. Mark Rasnake, Cashe was a hero.

“I did not realize it at the time, but he is the closest thing to a hero that I likely will ever meet. This is a place where the word ‘hero’ is tossed around day in and day out, so much so that you sometimes lose sight of its true meaning,” Rasnake wrote in a letter home, later published by the Air Force. “His story reminded me of it.”

The military doctors in Iraq worked “for hours” on Cashe’s wounds, Rasnake said, but the damage to his lungs was severe. Ultimately he was flown to Germany — the air evac team delivering “every breath to him during that flight by squeezing a small bag by hand,” according to Rasnake’s letter — and then to Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas.

His sister, Kasinal Cashe White, told the Los Angeles Times that when her brother was finally able to speak, his first words were: “How are my boys?” He died just weeks after the incident, on Nov. 8, 2005. He was ultimately responsible for saving the lives of six soldiers.

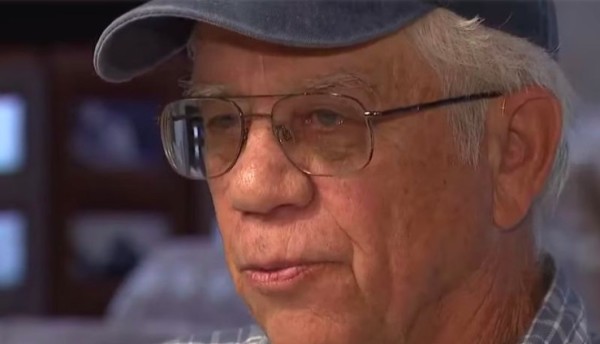

“Sgt. Cashe saved my life,” one of those soldiers, retired Sgt. Gary Mills, told the Los Angeles Times. “With all the ammo inside that vehicle, and all those flames, we’d have all been dead in another minute or two.”

“My little brother lived by the code that you never leave your soldiers behind,” Cashe’s sister, Kasinal, recalled to the Times. “That wasn’t just something from a movie. He lived it.”

Rasnake told Military.com just last year that Cashe’s actions were awe-inspiring among he and his colleagues, who believed if “his actions don’t deserve the Medal of Honor, we had trouble imagining anything … that would.”

More great stories on Task & Purpose

- Air Force C-17 crews are exhausted but proud after largest airlift in US military history

- The Pentagon’s filtered version of the Kabul rescue mission looks nothing like what really went down

- Before they left, US troops gave the Taliban and ISIS the middle finger in messages left at the Kabul airport

- ‘That’s what I’m here for’ — What it’s like to deploy the barriers at a military base gate

- Marine commander relieved over viral video calling out military leaders for Afghanistan withdrawal

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Learn more here and be sure to check out more great stories on our homepage.