The Navy’s electromagnetic railgun was supposed to be the weapon of the future — a super-powered cannon capable of liquefying targets at up to 100 nautical miles away with a solid metal slug that travels at speeds up to 4,500 mph. But after years of troubled development, the much-hyped supergun appears stuck in a research and development black hole, according to sources with direct knowledge of the program and budget documents reviewed by Task & Purpose.

“The railgun itself has overcome all the required technical hurdles, but the systems simply aren’t in place to take advantage of its capability and speed — the fire control systems, the communications link with a command center,” a source with direct knowledge of the program told Task & Purpose. “If there’s no funding, the program can’t move forward.”

The railgun seemed poised for a major breakthrough in 2017. That year, officials at the Office of Naval Research released a sizzle reel of the powerful weapon system developed by BAE Systems and General Atomics, showing it firing several rounds at Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division with speeds reaching up to Mach 6 at a high rate of fire.

It was a preview of what a railgun’s battlefield operations might actually look like.

But the Navy’s budget for the electromagnetic railgun, which has cost the service more than $500 million in research and development since it was first conceived in 2003, has all but dried up in recent years. As part of the service’s fiscal year 2021 budget request, the Navy requested just $9.5 million to develop advanced tech associated with the weapon system, down from around $15 million requested in fiscal year 2020 and roughly $28 million in fiscal year 2019.

The venture hasn’t completely stalled. The decline in funds between the Navy’s fiscal year 2020 and 2021 budget requests reflects the zeroing out of a $7 million line item focused explicitly on applied research and the addition of an additional $2 million towards technology development, a sign that the project’s focus has pivoted more towards the latter than remaining stuck in the former. Indeed, the electromagnetic railgun underwent what officials described as “essentially a shakedown” of critical systems in June of last year, with tests designed to stress the weapon’s power system and universal mount. The Navy even floated the idea of potentially conducting a ship-board demonstration in the Pacific Northwest months later.

But despite these recent advances, budget documents appear to indicate that the weapon’s power system and common mount are both still works in progress, forestalling the possibility of an imminent ship-board test. To wit, the systems are still included in Navy’s budget documents as still in process, implying that service’s fiscal year 2021 plans for the railgun — listed only as ‘N/A’ in the documents — are essentially the same as the previous year. And as of December, the service’s railgun prototypes were still undergoing testing at Dahlgren without any inkling of a future shipboard demonstration.

The Office of Naval Research and BAE Systems both declined to comment for this story.

This wouldn’t be the first time that shipboard testing for the railgun has been postponed: Back in 2015, Naval Sea Systems Command announced plans to test the supergun aboard the Spearhead-class expeditionary fast transport USNS Trenton (a substitute for the USNS Millinocket) off the coast of Florida some time during the following year, a test that was later delayed indefinitely.

But taken together with the steady decline in funding, one can presume that the Navy’s supergun is headed for an R&D “valley of death” between testing and procurement, wherein promising technology remains stuck in the research phase due to lack of resources or some other developmental challenge.

“Transitioning military technology efforts from the research and development phase to the procurement phase can sometimes be a challenge,” as a Congressional Research Service report on the Navy’s directed energy efforts puts it. “Some military technology efforts fail to make the transition.”

As Task & Purpose previously reported, the final development of a universal common mount is critical to actually demonstrating the tactical feasibility of the project far better than the rep-rate test at Dahlgren. Without it, the railgun is just another fancy piece of weaponry resigned to isolated testing ranges rather than the bow of a warship where it belongs.

Indeed, the universal common mount is a major sticking point for railgun advocates concerned over the project’s current status. In a letter to members of the House Defense Appropriations Committee in early March, Rep. Jim Langevin — Democrat from Rhode Island and co-chair of the Congressional Directed Energy Caucus — urged lawmakers to allocate an additional $50 million to “allow for the integration of a prototype mount to outfit the railgun system onboard the U.S. Navy’s new large surface combatant,” a sign that the Navy’s existing budget ask is woefully inadequate in moving the system forward.

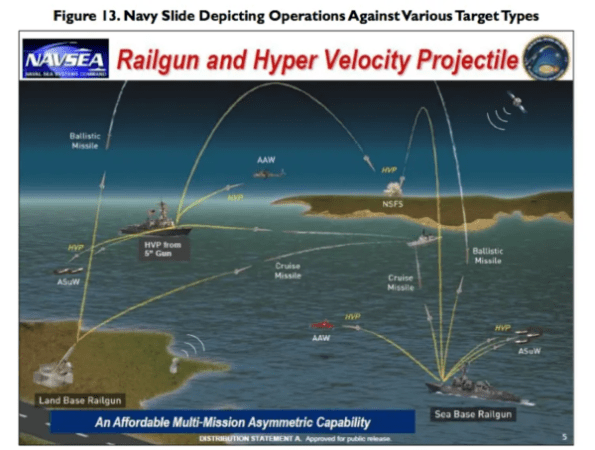

“A multi-mission railgun weapon system on the large surface combatant will provide capabilities like long reach, high energy on target, variable shot-to-shot muzzle velocity, and deep magazines to cost effectively combat emerging land, sea, and air threats,” Langevin wrote.

Translation: Once you actually see the electromagnetic railgun in action, you’ll understand why it’s worth the investment.

Both the technical and budget shortfalls, however, come during a period of waning interest in its potential application. As Task & Purpose has previously reported, the Defense Department has in recent years shifted its attention (and funding) from the railgun itself to the so-called hypervelocity project (HVP), a super-dense shell that, once envisioned as ammo for the Navy’s super gun, has seen cheaper and less technically complex applications to conventional powder artillery.

“The Navy feels it can get away with using the HVP in a conventional gun system, and the service can use conventional guns for lower-end threats and always return to missiles for higher-end threats,” the source told Task & Purpose. “The service will only complete the integration when the need for the greater capability for a broader range of threats is required.”

Until that need arises, the long-term engineering challenges may simply prove too insurmountable for a shoestring budget to address. Less than a year after declaring the Navy “fully invested” in the service’s much-hyped electromagnetic railgun, then-Chief of Naval Operations Adm. John Richardson in February 2019 telegraphed buyer’s remorse over the weapon’s troubled development, declaring the project “the case study that would say, ‘This is how innovation maybe shouldn’t happen.'”

“We’ve learned a lot and the engineering of building something like that that can handle that much electromagnetic energy and not just explode is challenging,” Richardson told an audience at the Atlantic Council at the time. “So, we’re going to continue after this — we’re going to install this thing, we’re going to continue to develop it, test it … It’s too great a weapon system, so it’s going somewhere, hopefully.”

As it stands, the electromagnetic railgun is still very much alive as a weapons program. But despite Richardson’s optimism, evaporating funding and frustratingly piecemeal technological advances appear to have doomed the the Navy’s supergun to a slow death, left to toil in obscurity without ever seeing the glorious light of battle.

Then again, it may be too late for the weapon anyway: one of China’s Type 072III-class landing ships was spotted roaming the high seas with its very own railgun turret as recently as December 2018.