In early November, Iranian-backed Yemeni rebels fired a ballistic missile at the far-off Saudi capital of Riyadh, retaliation for Saudi Arabia’s aerial intervention against them in Yemen’s civil war. Luckily, Saudi defense officials said, the missile was tracked and destroyed by their U.S.-made Patriot Advanced Capability-3 (PAC-3) kinetic interceptor before it reached its target, King Khalid International Airport — potentially preventing a worse outcome from what CNN described as “the first time the heart of the Saudi capital has been attacked and… a major escalation of the ongoing war in the region.”

President Donald Trump captured the Patriot’s apparent triumph, and the treacherous regional politics behind the attack, as only he could: in a sales pitch that could have been for Flanagan auto parts, if Flanagan auto parts could start World War III. “A shot was just taken by Iran, in my opinion, at Saudi Arabia … and our system knocked the missile out of the air,” Trump told reporters on Nov. 5. “That’s how good we are. Nobody makes what we make, and now we’re selling it all over the world.”

Trump’s jab against the Iranians naturally started an international flap, but the sales part of his comments may have been wrong, too, with huge consequences, according to a month-long analysis detailed in the New York Times. The Saudi interceptors failed five separate times during the Riyadh attack, and bystanders in the missile’s target — the capital’s airport — recalled being rocked by a nearby ground explosion. Those reports could mean a failure that will alarm the 14 U.S. allies fast embracing the American-made missile-killer to counter threats from North Korea to Russia.

“The Houthis got very close to creaming that airport,” Jeffery Lewis, the analyst who led a group of independent missile experts and defense researchers in the painstaking month-long investigation, told the Times. “Governments lie about the effectiveness of these systems. Or they’re misinformed … and that should worry the hell out of us.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iKezL521mEI

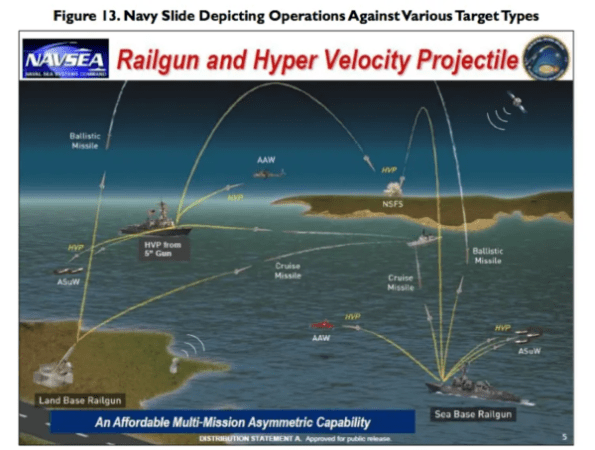

Lewis and his team spent weeks poring over eyewitness photos and videos circulated on social media. They believe from the timing and location of the Yemeni Burqan 2H missile impact and resulting debris that the missile may have completely evaded the Saudi PAC-3 batteries. Video evidence shows emergency vehicles responding to a fireball and tower of smoke at the end of an airport at King Khalid International Airport following a “loud bang” that rocked the airport’s main domestic terminal. Given that photos of the debris some 12 miles away from the blast revealed only the missile body and engine, analysts told the New York Times that the warhead continued on “unimpeded” to its target, exploding at the end of the airport runway.

When good data brings bad news: @ArmsControlWonk & @mhanham analyze @planetlabs picture of likely Scud missile strike near Riyadh https://t.co/V2QFT3Nf8Q pic.twitter.com/Lght3I2PVj

— Rob Simmon (@rsimmon) December 4, 2017

And that’s the suggested best case: only if one of the PAC-3 interceptors took out *just* the engine and body. The analysts managed to isolate video of the Saudi Patriot batteries in action, video that showed the warhead travel “well over the top” of the interceptors.

Video: #SaudiArabiaCoup

Anti missile defense system in action over #Riyadh skies. pic.twitter.com/rbVVdd04vr

— BlueTexan (@lkjtexas) November 4, 2017

“Saudi officials have said that some debris from the intercepted missile landed at the airport,” the New York Times reports. “But it is difficult to imagine how one errant piece could fly 12 miles beyond the rest of the debris, or why it would detonate on impact.” Indeed, even U.S. defense officials interviewed by the New York Times expressed doubts that the Saudi system achieved its designed goal.

That’s a startling admission given the rapid adoption of the PAC-3 to address looming missile threats. Defense contractor Raytheon, whose batteries actually launch the 600 made missiles that were sold to the Saudis in July 2015, claimed shortly after the incident that its systems in the Middle East have slapped down more than 100 tactical ballistic missiles since 2015. The Saudi missile defense network has been undergoing an upgrade for the last year, and while the PAC-3 only constitutes a fraction of the Trump administration’s proposed $110 billion arms transfer to Saudi Arabia, the House of Saud is an increasingly attractive buyer for both the U.S. and its European allies.

The Saudi PAC-3’s alleged failure may generate a ripple of anxiety among Raytheon’s current (and future) buyers. On Nov. 27, the Army announced that it had completed operational tests for a new Patriot missile as part of a year-long effort to bolster South Korean defenses amid rising tensions with North Korea. On the same day that the Timespublished the results of Lewis’ investigation, the Japanese Ministry of Defense announced a $94.8 million overhaul of its Japan Aerospace Defense Ground Environment intercept system, an overhaul that includes 28 PAC-3 surface-to-air interceptors in operation by 2020. And beyond North Korea, the Pentagon has been approving Patriot missile sales in Eastern Europe for a year to, alongside its new SHORAD requirements, effectively counter a resurgent Russia.

If there was indeed a major error in the skies above Riyadh on Nov. 5, it remains unclear if that was an operational failure by the Saudi military or a technical one on the part of Raytheon’s mythologized, contract-winning missile-defense battery. But one thing is clear: Pretending it didn’t happen is the worst possible way to address a potential chink in the U.S. anti-missile armor.

WATCH NEXT: