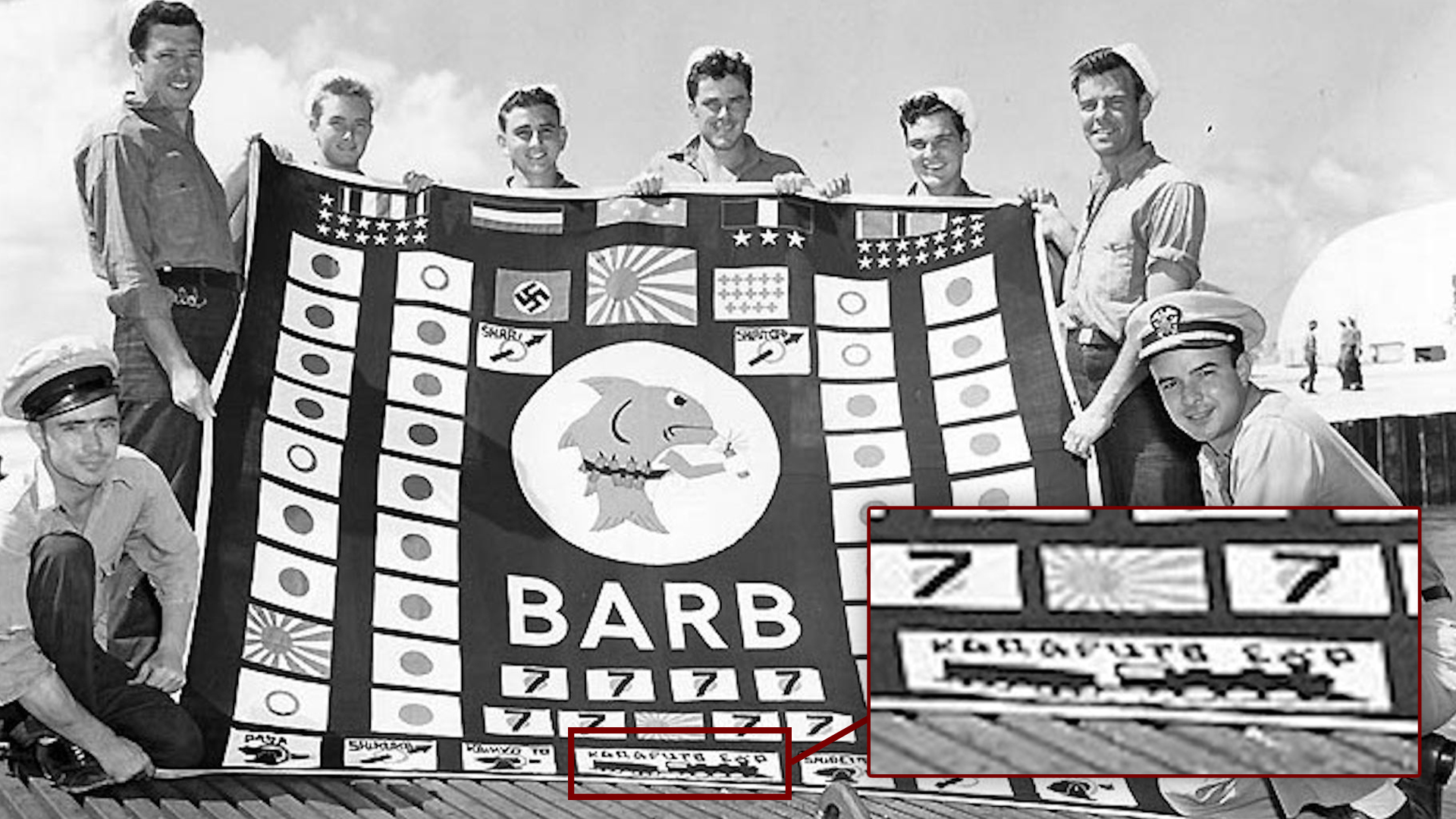

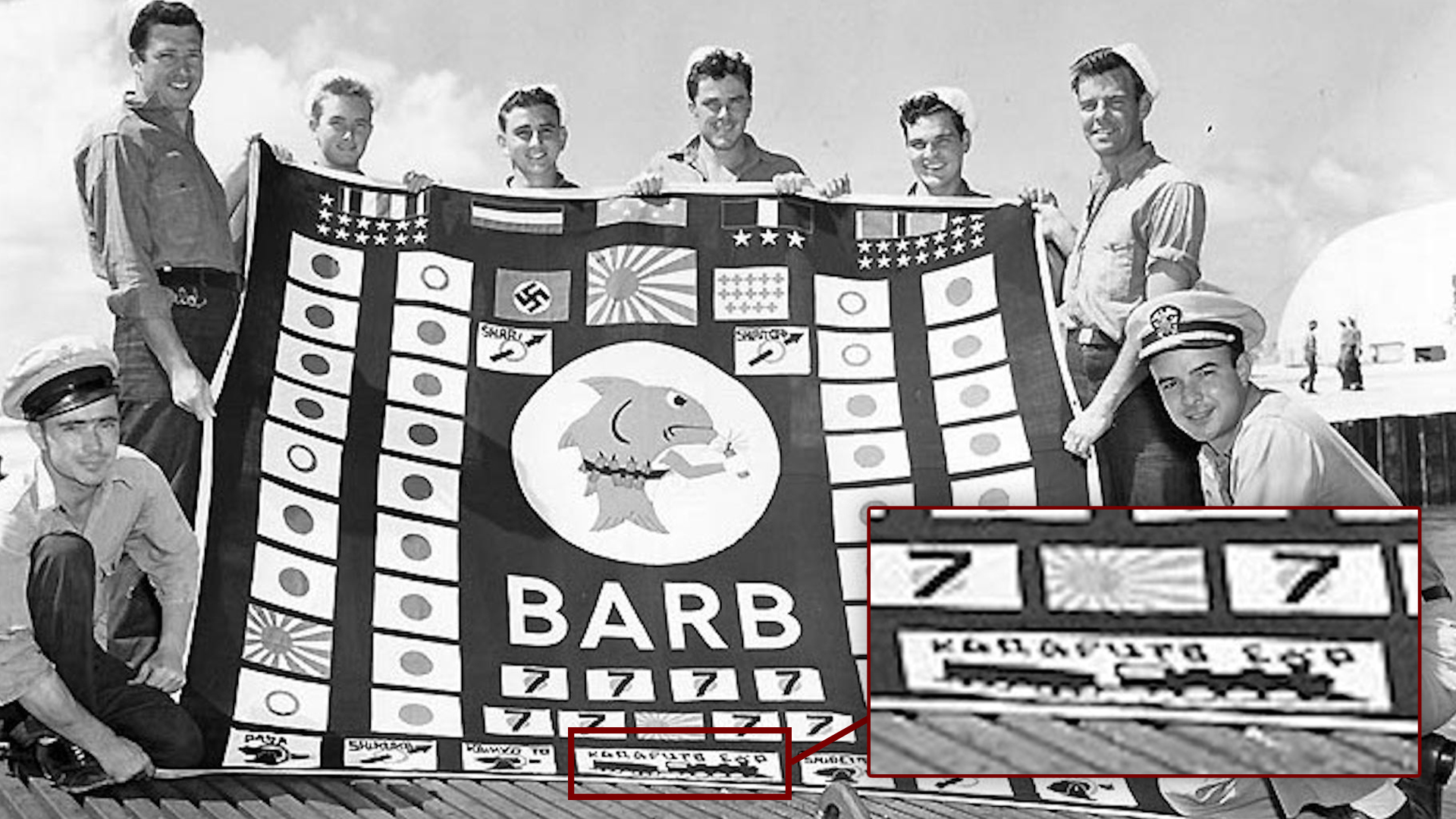

In August 1945, eight members of the crew of the USS Barb posed for a photo at Pearl Harbor holding up the submarine’s battle flag. The different patches on the flag represented the boat’s myriad accomplishments over 12 patrols in both the Atlantic and Pacific theaters. Seventeen ships sunk, a Presidential Unit Citation awarded following its 11th patrol, and the Medal of Honor was awarded to the ship’s captain, Cmdr. Eugene Fluckey. But, most unusual, the flag also featured a kill marking for a train. Yes, a train.

On the USS Barb’s final patrol of the war, the eight men in the photo had destroyed a Japanese locomotive, a most unusual kill for a Navy submarine.

A few weeks earlier, the Gato-class submarine was patrolling the Sea of Okhotsk, off the shore of what is now Sakhalin Island but was then part of Japan’s Karafuto Prefecture. Within a month, the war would be over, but the USS Barb had already racked up an impressive combat record. Commissioned in 1942, the USS Barb was initially one of the few U.S. Navy submarines sent to the Atlantic theater. Over the course of five patrols, it recorded just one possible sinking of a German freighter before being sent to the Pacific in the fall of 1943, where the Barb would make its name as one of the most lethal submarines in the fleet

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

Fluckey, the submarine’s commander, had joined the ship for its seventh patrol, and took command of the boat on April 28, 1944, ahead of its eighth mission. As Fluckey wrote in his 1992 account of his wartime service, Thunder Below!, he guaranteed Vice Adm. Charles Lockwood, commander of all submarines in the Pacific, at least five kills before departing; a promise which he fulfilled. In the first four patrols with Fluckey in command, the USS Barb sank more than a dozen Japanese Navy ships, including an aircraft carrier, as well as numerous other small vessels. The Barb conducted shore bombardments and rescued British and Australian prisoners whose ship had been sunk by another American submarine. Fluckey himself was awarded the Medal of Honor for maneuvering through shallow water of a harbor along the Chinese coast and sinking three ships, along with damaging three others, as well as three Navy Crosses. In addition, the crew earned a Presidential Unit Citation for the success of the patrols.

In the Sea of Okhotsk, Fluckey and the crew observed the rail line. After several days, Fluckey and the chief of the boat, a 26-year-old sailor named Paul Golden “Swish” Saunders, devised a plan. Saunders was the most experienced submariner aboard — he had joined the Navy when he was 17 and had served on the USS Barb since it was commissioned, sailing from the coast of North Africa to the North Pacific, for all of the submarine’s 12 patrols.

The plan was relatively simple: Eight men would paddle ashore on two inflatable boats and plant an explosive charge along the rail line. Every member of the crew had volunteered, but given the risks of the mission, Fluckey selected them based on his own criteria — he wanted only unmarried men, and preferably those with some scouting experience.

Saunders, along with electrician’s mate Bill Hatfield, rigged a 55-pound bomb. It was made from a scuttling charge wired to three batteries and placed inside a pickle can. Hatfield also improvised a detonator that would be triggered by the weight of a train passing over it.

Shortly after midnight on July 23, 1945, the USS Barb surfaced 950 yards off the shore of Sakhalin, and the eight men, among them Saunders and Hatfield, set out. They had about three hours, as Fluckey told them that the submarine would have to submerge before dawn.

“Boys,” Fluckey told the men, according to the U.S. Naval Institute, “if you get stuck, head for Siberia 130 miles north. Follow the mountain ranges. Good luck.”

Leaving two men to guard the boats, the shore party made its way toward the railroad tracks. Reaching it, three men were posted as sentries, and three others got to work setting up the explosive. At one point, a train passed by, forcing them to take cover. Eventually, the team was able to set up the explosives, and the men began making their way back to the beach and then out to sea. When they were still only halfway to the USS Barb, the sound of an oncoming train could be heard. As they climbed back aboard the sub, a massive explosion could be seen.

“The boilers of the engine blew. Engine wreckage flying, flying, flying up some 200 feet, racing ahead of a mushroom of smoke, now white, now black. Sixteen cars piling up, into and over the wall of wreckage in front, rolling off the track in a writhing, twisting maelstrom of Gordian knots,” Fluckey wrote in Thunder Below!

Though it may have been the work of the submarine’s crew, for the purpose of accolades and public recognition, the USS Barb was considered to have “sunk” a train.

It wasn’t the only first for the patrol. Before departing, Fluckey had requisitioned 72 Mk. 10 rockets along with a launcher.. In between becoming the only submarine to sink a train, the USS Barb also became the first submarine to launch ordnance of that kind.

The USS Barb returned from its final patrol to Midway Island on Aug. 2, 1945, one of the most decorated U.S. Navy submarines of the war, and also the only submarine to have ever sunk a train.

The latest on Task & Purpose

- Marine shown fighting with San Diego hotel staff in viral video charged with assault and battery

- Air Force cadet died of blood clot in lung, autopsy finds

- Airmen prepare to bid farewell to beloved ‘Big Sexy’ refueling tanker after 30 years of service

- The US appears to have used its missile full of swords in an airstrike in Yemen

- What the chances of a war between the US and China actually look like, according to experts

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here.